PER ARDUA AD ASTRA

PER ARDUA AD ASTRA

"through adversity to the stars" or "through struggle to the stars"

December 18, 1944 It wasn’t a terribly good day all things considered. There was a general optimism that the war was going better but for those on the battle lines the dangers were still front and centre. If you were a sailor in the U.S. 3rd Fleet you would have thought the world was coming to an end. Typhoon Cobra struck with a vengeance in the South Pacific and scattered the fleet. Aircraft carriers with flight decks that were usually sixty feet above the water were now dipping these same decks into the green ocean and struggling to stay upright. Ships were rolling through 100 degrees of arc and visibility was down to a few meters in the torrential rain. Three destroyers were lost in the mountainous waves.

In Europe, it was man pitted against man. The Germans were two days into their Ardennes offensive. They had put together 14 infantry divisions and 5 Panzer divisions and caught the Americans flat-footed. The Germans were trying to split the Allied forces by driving a wedge through Brussels to Antwerp, Belgium. Their efforts resulted in smashing the 106th Division of the American Army. 7,500 Americans surrendered in the largest mass surrender in American fighting history. The resulting Battle of the Bulge was difficult and costly but thankfully it was the last offensive Germany would mount.

For Jim Parrott and his six crew members, all this was irrelevant. Their day was going to be long and difficult. It had started the night before at Croft, in the north of England at 2300 hrs. with a Navigation Briefing for their early morning mission. This meeting was followed with a Main Briefing at 2356 hrs. The emotions were running high and there was too much adrenalin in the system to notice the lack of sleep. Their whole attention was focused on the details of the mission ahead.

0220 hrs.

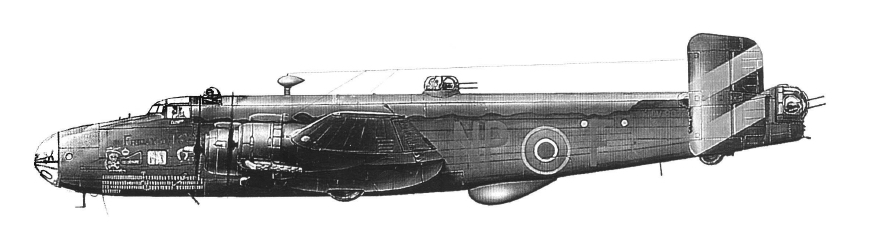

The four massive Bristol Hercules radial engines crackled to life with a thunderous roar and settled into a teeth rattling warm up as WL-U stood poised on the taxi runway. The crews of the eleven aircraft that were lined up for take off tried to settle their emotions and make final preparations. It was one of those times of personal crisis when significant events in a person’s life can be recalled in brief flashes. Perhaps this happened to Jim Parrott despite his best efforts to focus on the mission and bring to bear the three and a half years of intensive training he had received. This was to be his fifth sortie over enemy territory on a bombing mission. Each time he had the same crew with him and there was a comfort level in knowing each of these men as well as he did. Everything had happened quickly since he was put on strength in the squadron on the 25th of October, a few short months before.

The first week of November was spent in the sickbay at Croft because he had twisted his knee while on a flight and aggravated an old injury. Once the swelling was down and he had good function again, the training flights were resumed to hone their skills in preparation for the big day when they would do their first mission together. It was not far off! On 16th of November, Bomber Command had been asked to bomb 3 towns near the German lines which were about to be attacked by the American First and Ninth Armies in the area between Aachen and the Rhine. They were to be one of the 1,188 aircraft sent to attack Duren, Julich and Heinsburg in order to cut communications behind the German lines. Their particular target was to be Julich but after getting away to a good start at 1236 hours, they had a problem with the inboard starboard engine before they could reach the target area. The oil pressure had dropped to the danger level and the water temperature had risen to a level that threatened a fire if they were to continue. According to procedures they had to turn back and jettison the bomb load over water before landing. They had been in the air for a little over three hours and were disappointed that they had to abort their first combat mission. They didn’t have long to worry about it; however, as they were in the air again on the 18th. This time they took off at roughly the same time and headed for Munster as part of a 479 plane raid. Everything went according to plan and they were able to bomb their target from 17,000 ft using the red and green sky markers that had been set by the Pathfinders. There had been too much cloud to assess the accuracy or effect of their drop. The bond between the crew grew that much stronger knowing that they had done their job well.

Three days later on the 21st they were in the air once again headed toward Castrop-Rauxel in “Happy Valley” as the Ruhr was sarcastically called. Takeoff was at 1655 hours and this was the first time they could put all their night flight practices to use. It was a very busy night as there were a total of 1,345 sorties flown by Bomber Command. They were one of 273 aircraft that were allocated to bomb an oil refinery at Castro-Rauxel and the mission had gone well. They were over the target at 1904 hours at 18,000 feet and the weather was clear. Again they used the red and green markers for alignment and were able to see one large explosion with dense smoke as a result of the bombs they dropped. He remembered marking in his log “Good Effort”, “Good Trip” after they had returned to Croft at 2231 hours. It had been a long day for them and they tried to ignore as well as they could the fact that in total 14 aircraft were lost on that mission. At 1%, losses were much more acceptable than in the early days of the bombing campaigns, but they were losses all the same.

On November 27th they participated with 290 other aircraft in a raid on Neuss. It was another night flight and they were up in the air at 1655 hours and over the target at 2029 hours. That night their payload comprised 1-2000 lb., 7-1000 lb., and 6-500 lb. bombs. On the return flight the weather closed in and they were forced to land at Methwold instead of Croft. This was not unusual because it was winter and in the north of England and many flying days were lost because of heavy storms and dense fogs. The next day on the 28th the weather cleared and they were able to fly back to Croft. It had been a long haul and they were all tired.

Croft was home. For the Canadians who came from small towns and farms it had a familiar feel about it. In the north of England, just south of the Town of Darlington and situated on the North York Moors, it was a long way from the industrial midlands and the more built up areas in the south. The base was thrown together in the rush of trying to significantly increase the capacity of Bomber Command in the early days of the war. The first occupier was 78 Squadron of the R.A.F. in October of 1941 and they had to tough it out under pretty rough conditions that first winter. Their original Whitleys were replaced with Halifaxes in April of 1942 but by June the runways had been so damaged by the much larger and heavier planes that the airport had to be closed down for three months for extensive repairs. The main runway was lengthened from 4650 feet to 6000 feet and made 150 feet wide.

At this time a wire arrestor system was installed at the end of the runway closest to the railway track. Heavy cables were strung across the runway and connected to hydraulic dampers that were buried in the ground in order to catch any airplane that could not stop on the concrete. It was not uncommon for planes to overshoot a runway and come to a successful stop on a railway track only to be hit by a passing train. Too many aircrews were lost this way. All airfields had railways in close proximity for the delivery of fuel, bombs and other supplies. The large quantities required and the heavyweights would have been impossible to move via the road system.

The first R.C.A.F. squadron, No. 419, made its presence felt in October of 1942 with their inventory of Wellingtons. By the end of the year they were converted to Hallies and transferred to Topcliffe. In January of 1943, No. 6 Group was formed within Bomber Command to bring together all of the Canadian squadrons under Canadian command. Originally it comprised six bomber squadrons with the 427 at Croft flying the Wellington Mk. III. They were to stay for only four months before moving to Leeming. For the next seven months Croft was occupied by No. 1664 Canadian Heavy Conversion Unit. The conversion units were vital for the training of the many crews required to fly the Halifaxes and Lancasters. Preliminary flight and navigational training for most Commonwealth fliers was carried out in Canada but final training was done in England in these Heavy Conversion Squadrons. At the end of 1664’s stay the base was to be occupied by two more Canadian heavy bomber squadrons. The Iroquois No. 431 and Bluenose No. 434 were transferred from Tholthorpe and were to remain at Croft for the rest of the war.

Continual improvements had transformed Croft into a well functioning base and a more liveable setting for the occupants. Apart from being an airport, the base was home to the fliers, ground crew and all the support staff required to carry out the operations, including an antiaircraft unit for their protection. In many ways it was a sizable self contained city filled with young men and women who despite the constant contact with death and destruction, managed to create a social structure that went a long way to keeping their lives on a sane and even keel. For example, a ten team, Canadian Northern Ice Hockey League was formed and the games were played in the Durham Ice Rink in Darlington. Teams were made up from the surrounding bases with Canadian fliers. Milt Schmidt of the Boston Bruins and many other enlisted National Hockey League players would have made the calibre of hockey very interesting despite the fact the arena had roof support pillars in the playing surface!

Photo: Alex Divitcoff (on the far right) joins the boys in the crew room for a game of four handed cribbage to take their minds off business.While they sat and waited for the order to take off, Jim Parrott had to think back in brief flashes as to how he got there. He signed up with the Royal Canadian Air Force in Markham, Ontario on May 16, 1941. He had been working as a milk salesman for the Roselawn Dairy in Toronto and wanted to be involved in the war effort. He was born on the prairies and his earliest memories were of the waving wheat fields of their farm in Laura, Saskatchewan. His father died from complications following an appendectomy when Jim was five years old and because his mother was unable to manage the farm on her own, they moved with his older sister and younger brother to his mother’s childhood home in Markham, Ontario. They lived with his grandfather and his mother’s sisters but nothing made up for the father he had lost. Jim attended high school and was active in sports but further education was out of the question as it was necessary to bring some income into the family. The depression had not been easy despite his grandfather being a blacksmith of local renown.

Life in the Air Force meant total immersion in the business of flying. There had been intensive training with much of his time spent at the navigation school in Rivers, Manitoba. His flying had progressed from dual to single control Finchs and Harvards and then to Ansons and heavier-multi-engine crafts. In January of 1943 he was promoted to Flying Officer and in November of the same year he took the big personal step of marrying Patricia Hopper in the Y.M.C.A. in Windsor, Ontario. Why the Y.M.C.A.? Well it was just there and they were in a hurry. One month later on November 16th he embarked from New York for England and he had not been home since. After spending time in a heavy conversion unit to train on a Halifax he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in July, 1944. Despite the personal pride he took in getting this promotion it was not a time to celebrate because he had also received word that his mother had died that month. She had been suffering terribly from cancer and the family requested that he be given leave to come home and visit with her before she passed away. The War Office was sympathetic but would not allow a leave because of the pressing requirement for new aircrews in Bomber Command. Jim was put on strength with No. 434 Bluenose squadron on October 25, 1944.

At 24 years of age he now had a mountain of responsibility on his shoulders. He had always tried to make up for his missing father in the family setting but this was different. He was not only in command of the aircraft but he was responsible for the lives of his six crew members who had become closer than family over the short time he had known them. Down in the nose of the plane was Flight Sergeant Allan Kurtzhals from Salmo, B.C. also 24 years old but single. He would spend most of the flight today in a prone position trying to be comfortable. It was his job to guide the plane on the bombing run and release the bombs at the right point to hit the target. This was not a minor accomplishment considering the plane would be flying at around 20,000 feet at a speed of approximately 300 miles per hour. To make the job more difficult, consideration had to be given to cross winds and the aerodynamics of the ordinance being dropped. If required he would also have to get up and fire the machine gun mounted in the nose of the aircraft.

In the small compartment about a metre square behind the bomb aimer sat the navigator, Harry Pearce, from Drumheller, Alberta. At 28, and also married, Harry shared the status of being the oldest member of the crew. Jim and Harry had been together in the 1664 Heavy Conversion Unit and it wasn’t easy to forget the close call Harry experienced earlier in the year. On a night training flight out of Dishforth on April 15 his plane was caught in an intense storm on its return to base. The two port engines on the Halifax had failed so they were given permission to land despite a 10 mph tailwind. On breaking through the cloud cover the pilot realized that he had overshot the runway and tried to rescue the situation by putting down on an adjacent field at Topcliffe. Unfortunately, the plane clipped a cottage on its descent and crashed. Harry and air gunner John Tyinski were the only two out of the seven to survive the impact and fire that followed. It had taken several months for Harry to recover from his injuries but he could not forget the loss of his friends. Harry’s small area was crowded with navigational aids; a G-set for radio navigation, an H2S (code word for ground scan radar) cathode ray screen, air and ground speed indicators, a dead-reckoner and a compass. There was an overhead fluorescent light, a small desktop and a chart rack all designed to bolt down so as not to fly around when violent evasive action was required. In the early days of the war navigation was a very hit-and-miss endeavor but by December of 1944 there had been a lot of progress with electronic beacons and the use of the Pathfinder Force to act as the navigational leaders of each mission.

Behind the navigator and almost directly below the pilot sat the Wireless Operator. P/O Bert Brown. Bert was also 28 and had lived in Wetaskiwin, Alberta before the war. His father was a partner in a car dealership and Bert probably had visions of returning home to take part in the family business. He could think about settling down with Cora, the girl he had married in February 1943 just before he left for overseas. It was all too clear to Bert that his future was not exactly a foregone conclusion because he had already been in two training crashes back in Canada. He survived a crash on Vancouver Island and then went down in another crash in freezing rain in Alberta. The plane dropped into a grain field and slid forever on the ice before coming to a halt. He, like Harry, had experienced what happens when things go wrong. He also had the worry of knowing that his younger brother Jack was missing in action. Jack was also an airman and had been missing for six months after flying in the North African theatre and Italy. It was a real concern for both him and his family.

Sgt. Les Janzen occupied another compartment just behind the pilot. He was the flight engineer and it was his responsibility to monitor the mechanical workings of the aircraft. He had to constantly monitor the fuel situation and the condition of the engines. If the plane sustained flack damage or had engine problems Les would become very busy trying to jury rig something to get them home safely. On takeoffs, Les would reach over and control the centre-mounted throttles while the pilot fought to control the plane. It was a difficult and heavy job when the plane was fully loaded with fuel and ordinance. Les, who came from around Erwood, Saskatchewan was 24 years of age and single.

Two gun turrets provided the aircraft’s main defence against German fighters. There was an upper middle turret and the tail turret. Today, as in their previous four flights over Germany, F/Sgt. Gord Olafson would be manning the rear turret. Gord was another west-coaster who came from Stevenson, B.C. He had a cold and lonely position at the back of the aircraft and needless to say dangerous as well. This turret with its four .303 cal. Browning machine guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition was the main defence for the bomber. The German night-fighters tended to attack from the rear so Gord was in the direct line of fire. There had been occasions when a bomber would return undamaged except for having the rear turret completely shot away. Sometimes the gunners would remove the Perspex panel immediately in front of them in order to have a better view of an approaching fighter. It made their tiny compartment bitterly cold and the wind would be ferocious but for some gunners it was the only way to go. The earlier the detection of a fighter, the better the chance of the pilot pulling off a successful evasive “corkscrew” move and in most cases the warning came from the rear gunner. Gord was 23 years old and born in Stevenson, B. C. but his father Guttorm, a merchant seaman, was originally from Norway and his mother Barbara Witzgier was born in Germany and came to Canada before World War l. Gordon finished high school in 1941 and then went to work as a lineman for the Canadian Fishing Company for one year before enlisting in September 1942. At 5 ft. 9 in. tall and 121 lbs. he was ideally suited to fit into the rear turret. He had three brothers, Robert, Earnest and John who also enlisted and were serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The mid upper turret was manned by Flt./Sgt. Alex Divitcoff, the youngest member of the crew at 20. Alex was a Torontonian who came from Macedonian heritage who enlisted and began his training in the air in July of 1943 at the gunnery school in Macdonald, Manitoba. After an introduction to the cine gun camera he spent many rounds of ammunition firing at a moving beam target and an “over the tail” exercise. By the end of September he had spent 25 hours in the air and his initial training was over. By November he was in England and flying training flights in Wellingtons with the No. 82 O.T.U. This training involved day and night flights, cross country bombing circuits and air firing and by the time he was finished he had accumulated 69 hours of daylight flying and 45 hours of night flying. In February of 1944 Alex was assigned to the 1664 Heavy Conversion Unit and was training on Halifaxes based in Dishforth. He was assigned to several crews and it was not until the end of September that he joined Jim Parrott’s crew and he stayed with them when they were transferred to go “on strength” with 434 Squadron on October 25th. By this time Alex had 172 hours of daylight and 107 hours of night flying under his belt and he had excellent grades for his proficiency as a gunner. He had recently done two practice flights in the rear gunner position just before their last mission but today he would be in his familiar middle turret.

0250 hrs.

A quick check with the crew, release brakes and throttle up. It was time to get underway. Les held the throttles forward and the four, fourteen cylinder rotary engines producing 1,650 horsepower each hauled the big craft down the runway in the dark of the night. Fully loaded the plane weighed around 65,000 pounds and it took Jim’s full mental concentration and physical effort to get the plane into the air successfully. There was no margin for error in the speed at lift off or in the rate of climb. Any loss of power or failure of a control surface could result in disaster. Unfortunately, at another airfield where planes of the 425 Squadron were lifting off to join the raid, F/O J. Desmarais and his whole crew were killed when their plane crashed shortly after takeoff. Full of gasoline, bombs and incendiaries, there would have been a tremendous explosion. As their plane gained altitude the crew heaved a sigh of relief and settled in to the task of positioning themselves correctly within the mass of planes forming the mission. They were joined in the air by 187 other Halifaxes from the 408, 415, 420, 425, 426, 427, 429, and 432 squadrons along with 42 Lancasters from the 419, 428, and 431 Squadrons. The 400 series of squadrons were all part of 6 Group that was created for the Royal Canadian Air Force. In total there were 523 aircraft in the air after they were joined by British crews from Nos. 4 and 8 Groups. Croft was one of the most northerly fields in England utilized for raids on mainland Europe. As the Croft planes moved south at an altitude of about 8,000 ft. on a course set for Reading (just to the west of London) they were joined by other planes in closely choreographed lift-offs and flight plans. It was a maneuver that had been well-rehearsed by flight headquarters as almost every night, weather permitting, there could be more than a thousand planes in the air with many different destinations and targets. On this day there were also 317 Lancasters heading to Ulm, Germany, 280 Lancasters to Munich and 44 Mosquitoes were leading a “spoof” raid to Hanau while 26 more headed for Munster. Five more Mosquitoes went to Hallendorf to deliver their payloads.

A heading change was made at Reading and the convoy of planes proceeded in a more westerly direction over the English Channel towards the Charlerois area in Belgium. Their altitude increased gradually to an operational height of 17,000 ft. and they settled in on their new course with the aid of their “GEE” radio navigation coverage and only thing visible being the red-hot exhausts of the engines on the planes ahead of them.

Shortly after setting their course, the pilot reported to the crew that he was not feeling well but didn’t think he was bad enough not to continue. They became worried that perhaps his oxygen supply was not working so the Engineer and Navigator checked out the supply and piping but everything appeared to be working satisfactorily. Just to be sure, they brought out the portable oxygen bottle and hooked Jim up. He continued to feel poorly and appeared to be in some distress so Allan Kurtzhals left his position to sit up beside the pilot on the folddown seat to his right to give him any help that he required. The Navigator suggested on several occasions that they could turn back but the pilot refused saying that he would make it. They were several minutes behind and the plane seemed to be weaving a little but otherwise the weather was clear and there was no reported enemy activity.

0630 hrs.

The second turning point was rapidly approaching. One-half of the planes would turn to the north in a move that was intended to fool the enemy and the other half would head directly for Duisburg. This was a difficult manoeuvre considering the number of planes in the air, their close proximity to one another and the possible error in the position of each aircraft. Planes were stacked on three levels between 17,000 ft. and 21,000 ft. and separated from those ahead and behind by what was thought to be a workable margin but it was far from safe considering the they carried no identification lights. It was wartime and risks that would never have been accepted in peacetime were considered acceptable in an attempt to end a war that had already consumed millions of lives.

Suddenly Bert Brown saw the Navigator in the compartment ahead of him jump to his feet and fold his seatback. Because he was listening in on the Group Broadcast at that moment, Bert was not able to hear the intercom conversation between the other crew members on the plane. Perhaps if he had heard the pilot he would have known what caused Harry to jump up but his immediate reaction was that something terrible was about to happen. Instinct made him rip off his helmet and reach for his parachute to clip it on. As he did this the nose of the aircraft pitched violently upwards and then the whole plane rolled over on one wing. From this point on Bert had no recollection of what happened until he regained his senses while falling freely through the cold early morning air. His head was cut and bleeding and his chute was only clipped on one side. He struggled to hook up the other side and then pulled the ripcord and lost consciousness again.

What exactly happened to the plane will probably never be known but there are several possibilities. The most likely scenario is that a mid-air collision occurred between this plane and the plane just ahead of it in the group. The violent nose-up was a common evasive move to prevent imminent collision. What caused the two planes to be so close is entirely speculative as either one could have been in the “wrong” place for any number of reasons. Lending strength to this theory is the fact that another plane went down in the same area. A Halifax from 51 Squadron piloted by F/O B. M. Twilly crashed into the woods near Hainant with no survivors.

Another possibility was that WL-U, the plane piloted by Jim Parrott, was struck by another plane, or something else that fell from above. This theory is reinforced by the knowledge that a verified collision took place between two other planes at roughly the same location. F/O M. Krakowsky, piloting a Halifax from 432 Squadron, code named QO-O was involved in a mid air collision with LV-810 from 10 Squadron (R.A.F.) The only survivor of this accident was the pilot Krakowsky while 13 others perished. It may have been possible that a plane or part of a plane falling uncontrolled from above may have collided with this plane flying at a lower elevation and caused it serious damage.

The only other possibility is that a severe failure of the airframe of NR118 occurred without any contact with another plane. The plane was damaged earlier in its flying history and it is an outside possibility that some unidentified weakness caused the plane to break up in the air over Belgium as a result of the combination of stresses it was exposed to. It was not unheard of for this to happen to a heavy bomber but it would have to be considered a slim possibility.

Witnesses on the ground near the town of Couvin, Belgium saw a burning plane falling through the morning sky. Messieur Bodart , a teenager at the time, was sitting at the breakfast table in the family farm house. He heard the scream of a plane descending very close by and rushed outside to see what was happening. Despite the war going on it was seldom they ever got to see any planes at close range. He was in time to see the plane explode just before hitting the ground. The low angle of descent hurtled pieces of the plane for a great distance across the ground and into an adjacent stand of trees. It was a violent and horrific scene that he would never forget. One wing landed several hundred meters from the main crash site and the engines of the plane were buried in the ground in separate locations. Most tragic of all, six bodies lay strewn across what had moments before been a peaceful, idyllic farm field.

The American Army occupied the south part of Belgium at that time. The area to the north and east of Couvin was the main site of the Battle of the Bulge and as a result there was a large build-up of troops in the area. The Americans were very quick to arrive on the scene of the crash to recover the bodies of the aircrew and any material from the plane that would have been dangerous to the public or needed to be recovered for security reasons. The plane was carrying a full load of bombs and in excess of 20,000 rounds of ammunition when it crashed. There would also have been code books, maps, bomb sites and electronic navigational equipment that would have been useful if they had fallen into German hands. The bodies were recovered along with any personal artifacts and taken immediately to a cemetery that had been opened for American Army casualties located in Fosses-La-Ville, a town 40 kilometers north of Couvin.

Meanwhile Bert Brown fell silently and swiftly to earth beneath his parachute. This was not the sport parachute that one is accustomed to today. During the war, military parachutes assured a very rapid descent. The landing was at the threshold of what a person could reasonable sustain without breaking bones. The person hanging in a parachute was an ideal target for ground fire or air gunners and the intention was to get him to the ground as quickly as possible. A tree arrested Bert’s fall as he thudded to the ground. After wandering around for some time trying to get his bearings and unsure of whether he was in enemy territory, he met some Belgian farmers who did what they could to treat his head injuries and then helped him to the American troops. He was first taken to an American field hospital and then to a hospital in Paris. From there he was flown to England where he continued to convalesce in a rest home. When sufficiently recuperated Bert was repatriated to Canada.

What happened to the plane was severe and sudden. From Bert’s account, it was apparent that he was thrown from the plane, probably through a fracture in the fuselage. If he had been able to make his was to the emergency hatch under the navigator’s seat it would seem probable that at least one of the others would have made it free of the plane as well. If there was contact with another plane a number of the crew might have been severely injured as a result of the impact and consequently were unable to make their way free. It would be almost a certainty that the plane would have been on fire and wildly out of control as it descended. The violent spinning of the plane may have prevented anyone else from making his way out of the plane. It would have been a horrific and frantic time for any of the crew who were conscious, as the fall from 17,000 feet would have taken far too long.

0930hrs.

On return to England after the raid on Duisburg, the 10 remaining bombers of the 434 Squadron were unable to land at their own field because of bad weather. They landed at Little Snoring as an alternative. The time would have been about 0930 hrs. A number of the returning planes, including two from 434 Squadron, met opposition from German fighters. WL-N was attacked by a FW-190 but there was no damage to the bomber. WL-X was attacked by a ME-109 and the gunners on this Halifax fired off 700 rounds at the Messerschmitt sending it down through the clouds in flames.

WL-U was reported as missing and several days later on the 21st of December, the next of kin of the crew were notified by telegram of the “missing” status. A personal letter was sent later to extend further condolences. Bomber Command would know nothing of the fate of these young men until the American military reported their identification and burial. According to military policy, the families were not notified of the deaths until three months after the “missing” status was initiated. This delay caused great anxiety in the families of the missing. Patricia Parrott, as well as other wives and relatives, wrote the Ministry of Defence asking why she was not being given the details despite the fact that she knew Bert Brown had survived and could tell what had happened. The Ministry was consoling but not forthcoming; never giving a reason for the crash while leaving the families to imagine that the plane had been shot down.

Officials in Croft carefully inventoried all the possessions of the dead fliers. Every piece of their clothing, personal belongings, letters and log books etc. were listed and packed for shipment to the next of kin. Bank accounts and any other financial ties in England were closed or liquidated and the proceeds returned as well. Many of the fliers had bicycles to get around the base and into town but these were sold in England and the proceeds forwarded instead. It was not worth it to pack and ship them considering their low value. These actions marked the beginning of a long paper trail that was picked up in Ottawa to resolve all the legal and financial issues surrounding the deaths.

1600 hrs.

The bodies of Jim Parrott, Alan Kurtzhals, Harry Pearce, Les Janzen, Gordon Olafson and Alex Divitcoff were prepared and placed in heavy canvas body bags with their names clearly stencilled on the outside. The bags were then placed in rough wooden caskets that were again identified with the name of the deceased. An army padre conducted the burial services and they were interred at Fosses-La-Ville in the Belgium No. 1 American Military Cemetery along with some of the other Commonwealth fliers who perished over Allied territory that day. Six white crosses now marked the graves of these young men who had died so violently that day. The four planes that went down in the same area at roughly the same time that day carried a total of 28 crew members. Only two survived! Of the 1310 sorties flown by Bomber Command that night, 14 aircraft were lost.

1948

Prior to the D-Day landings, the Americans forecast the number of fatalities they would suffer on the march to Germany. Unfortunately, the plan significantly underestimated the losses, primarily because of the Battle of the Bulge, and as a result the number and size of the cemeteries was insufficient. At the end of the war a consolidation took place requiring the cemetery at Fosses-La-Ville to be removed. From the time that it opened on the 8th of September, 1944 to the end of the war, the cemetery had accumulated 2,199 American soldiers and the bodies of 96 “Allied Brothers in Arms”. The majority of these Allied fatalities were made up of fliers who were downed over American held territory and by the troops of the Chaudiere Regiment of the Canadian Army. Many American soldiers were removed to the United States at the request of their families but the bodies of the Commonwealth combatants were transferred to another cemetery at Leopoldsburg in northern Belgium. The six crewmen of WL-U were disinterred and the bodies were placed in metal caskets that were in turn placed in wooden cases for transportation to Leopoldsburg. This operation was done with great respect and care. They were reburied with full military honors at Leopoldsburg.

The people of Fosses-La-Ville adopted graves and cared for the fallen as if they were their own. Their respect for what these men had sacrificed for them was heartfelt and genuine and is still strong today. By July 12th all the bodies had been removed and the cemetery was closed. All that remains is a small monument recognizing the historic significance of the locale but it is not forgotten.

Leopoldsburg, Belgium

Leopoldsburg is a typical Flemish town in the Limburg (N/E) region of Belgium. Two beautifully kept cemeteries have been carved into a treed area on the outskirts of town. One cemetery honors the graves of Belgians who died in WWI. The gravestones are solid tablets bearing bronze plaques individually cast with the identity of the fallen soldier. The graves are arranged in sweeping curves and swirls with an almost poetic elegance. Just down the road is a second cemetery opened during WWII to receive some of the Commonwealth forces killed in Belgium. Among the 801 graves, arranged symmetrically in a mirrored pattern are two grave markers, identical to all the rest with the exception of a cross being engraved in place of the normal regimental emblem. The symbol is the Victoria Cross, the highest honor bestowed on a Commonwealth combatant. One of the two stones marks the resting place of John Harper VC., a corporal in the York and Lancaster Regiment of the British Army. He received the honour posthumously for his heroism in Antwerp 29 September 1944.

Photo: Joanne and Margaret planting flowers at the graves of the crewThe other stone marks the place of Major Edwin Swales VC. DFC. of the South African Air Force who began the war as a soldier in the Natal Mounted Rifles. He then fought in Egypt in 1942 with the 1st South African Infantry division with the rank of Sergeant Major. While in Egypt he became fascinated with flying and transferred to the South African Air Force where he acquired his wings in June 1943 and quickly progressed to join the R. A. F. in England. He was attacked by fighters on five different occasions on his 33rd sortie and for his coolness under fire was awarded the DFC. Flying ahead of the group as the “master bomber” on his 43rd operational sortie his plane was attacked several times and having lost two engines and leaking fuel, stayed over the target giving aiming instructions until the attack had ended. Despite having crash landed successfully twice before, he was unable to survive the crash on his return trip from this mission. He stayed at the controls allowing his crew to escape safely but was unable to save his own life.

Although these two men received the highest award for valour under fire, it is fitting that their graves are identical to those of the other servicemen buried here. All of these men died trying to do their best for exactly the same cause and for that they were all equal. It was a matter of fate as to how they met their ends and whether or not they were recognized by military honors. In the case of the crew of WL-U nobody knows the individual acts of heroism that took place in the plane as it hurtled to the ground. We are only left to imagine.

1994

Bert Brown, the sole survivor of the crew of WL-U, died of cancer in his home town of Wetaskiwin, Alberta. Bert’s parents were so grieved at the thought of having lost both sons in the war that his father sold his interest in the car business. They must have been overjoyed that Bert survived but the war had left an indelible mark on the family. Not only was Bert’s brother dead but his uncle was also killed in Italy with Canadian Forces. Bert worked at a variety of jobs and became the Fire Chief of the town in 1980. As recalled by his son-in-law, Bert never spoke willingly or in any detail about his wartime experience or the crash of WL-U. He only explained that the plane was blown out of the sky so his family assumed that it had been shot down. Bert never did reveal to his family the details of the flight he recounted to a military reviewer shortly after the crash. Most would agree that it is impossible to fully empathise with someone who has had to carry the burden of survival when comrades are lost. One thing Bert kept from the war was a photo of the crew posing in front of a Hallie. It was a memory that he couldn’t put aside and at the same time didn’t want to forget.

Janzen Lake

The Province of Saskatchewan honored their armed services personnel who died in WWII by naming natural features in the province after them. Lakes, islands, bays, rapids, creeks and peninsulas in the north of the province bear the names of their fallen. In most cases these are pristine natural features that remain virtually untouched by humans. No more fitting tribute could be given to these soldiers, sailors, and airmen who died to relieve the world of the oppression of man’s tyranny. Janzen Lake is in the north-east corner of the province, to the east of Lake Athabaska and just below the 60th parallel.

May, 2003

It was an enjoyable spring day in Belgium. The air was warm and there was a hint of rain in the air as the afternoon grew older. A group of about 100 people gathered on a quite country road outside the town of Couvin to unveil a stele honouring six young fliers who died when their bomber crashed at this site 59 years earlier. It was a moving and emotional time for the relatives of the fliers who were present and it was a time of reflection and gratitude for the local Belgians who attended.

Following the ceremony at the crash site, the group attended a reception hosted by the Burgmaster in a restored farm building in the center of Couvin. Gifts were exchanged and it was an opportunity for everyone to meet and socialize over food and beverages provided by the town. For the relatives of the fliers, it was a time to speak, first– hand, with locals who either witnessed the crash or lived in the vicinity at the time. It was an emotional experience that was heightened by the difficulty of communicating in French but the bon homi was overwhelming and the friendship genuine.

The ceremony was the result of the persistent efforts of Hector Maurage, a resident of Couvin, to identify wartime crash sites in the area and have steles (small monuments) erected to honor the Allied fliers who perished. For Hector, it has been a long and dedicated pursuit.

Photo: Margaret McIntosh, Leslie Green, Hector Maurage and Joanne HartAlso responsible was Leslie Green, of Weston-Super-Mare, England. Leslie’s mother was a cousin of Harry Pearce and Les grew up hearing the story of the crash. Wanting to know more of what happened, Les pursued British military records and on one of his trips to the continent made a side trip to Couvin to try to find the site of the crash. He was fortunate enough to meet Hector Maurage and from that point on, a team had formed to aggressively pursue the goal of recognizing this site. Leslie tirelessly tracked down information on the crew and was able to contact Margaret McIntosh, the sister of Alex Divitcoff and Joanne Hart, the niece of Jim Parrott, making possible their attendance, along with his at the ceremony.

December 2003

The crash of WL-U was a single event in the course of a great war that took many millions of lives. By itself, it did not have any measurable effect on the outcome of the war. The death of six young men in a plane crash was not significant enough to make headlines or catch the imagination of the public. But for six families spread out in communities from Toronto to Vancouver, the clippings they cut out of the newspaper in order to save a short, one column notice and perhaps a photo of their son or husband it would not have been more devastating or poignant had it been the whole front page. These families never got to hear the thunder of a thousand Halifaxes and Lancasters flying off overhead to bomb the enemy. They didn’t see their towns bombed and their neighbors die or have their homeland threatened by invasion. Their war meant sending loved ones away from a safe and hospitable environment to a foreign land to risk their lives for someone else’s freedom. It was the ultimate act of charity and in this case, sacrifice. Curiously, the families retained these newspaper clippings as their most tangible evidence of this sacrifice. They were more personal than the small pins provided by the government.

The monument in Couvin, for the first time, makes a significant, lasting, and appropriate recognition of this loss. It symbolizes the thankfulness of the Belgian people just as it symbolizes the personal loss to the families involved. May these men now rest in peace knowing they are not forgotten and that the significance of their sacrifice has not diminished but grown with time.

References:

Pilgrimages of Grace: A History of the Croft Aerodrome by A. A. B. Todd, self-published. Contact Alan Todd Associates, 41 Woodland Road, Darlington Co. Durham DL3 7BJ, England Airforce, The Magazine of Canada’s Air Force Heritage Vol. 27 No. 1, The Raid on Happy Valley by Alan Soderstrom National Archives of Canada No. 434 (Bluenose) Squadron by Wing Commander F. H. Hitchins, Air Historian Internet Wed Sites: A variety of sites generally found by keywords such as; Bomber Command, Halifax, R.C.A.F. Daily operations reports, Margaret McIntosh: log book of Alex Divitcoff and various photos

Appendicies

(1) The following is the address given by Mr. Debuc, the Burgmaster of Couvin at the unveiling of the memorial in Pesche on May 8th, 2003. The translation from the original French was provided by the Town Best Friends,

We are gathering to honor and respect those courageous aviators' memory (Messers Pearce, Parrott, Janzen, Kurtzhals, Divitcoff and Olafson) who gave their lives so that we can today live in peace. We are especially proud to pay homage to Mr. Brown, the only survivor of that crew.

Today, on May 8th – the Anniversary Day of the end of the war in Europe – it is an honour and a great pride for my colleagues of the district council, for our population and myself to welcome you on this ground, rich in historical associations. We are happy to greet the families of the missing fliers and tell them how much we enjoy having them here today. We thank you for coming and especially for your honoring your lost relatives. We are so grateful to you for that.

I would also like to acknowledge the presence of some Bomber Command veterans, some former Belgian 40/45 pilots, some former prisoners of war as well as some Canadian and Belgian military authorities. Finally, I would like to thank all of you absolutely and for wanting to share our feelings in remembering all the heroes of those tragic years.

On this Armistace Day, after experiencing a major conflict in Iraq, today’s event and memorial unveiling dedicated to the Canadian bomber crew will enable us to remind our youths and all those who haven’t experienced the 40-45 years, that brave people from Canada, America, England and elsewhere gave their blood so that today, we live in a free democratic Europe. Therefore I will quote some words I read in a daily paper: “There were seven of them, they were about 20 years old with their lives ahead and full of dreams. Like all youth, they were dreaming of building a house, a family and a safe and good world to live in. They didn’t know that on December 18th, at dawn, their dreams of peace would vanish in a country they did not even know but in a country, they wanted to be free.”

It is a good thing to remember how much we needed the Allies to give closure to the debacle with true democratic values.

We have to keep in mind their solidarity and brotherhood spirit, their sense of duty, of courage and self-sacrifice. We all wish those sacrificed lives can forever remain sacred for peace and freedom in the world.

Colonel Bouzin will now speak but before that I would like to thank Mr. Maurage, thanks to whom we are meeting here today. Your sense of good citizenship by which you remind us of those gallant soldier’s actions, is particularly important to us. Unveiling this memorial is more than a symbol. It shows we cannot and may not forget the PAST. These hours of remembrance will help us understand the present time and defend democratic values as those fliers did. May our future generations never forget this!

(2) Mr. Eric Bouzin, a retired Air Force Colonel, was unable to attend the ceremony because of ill health but made his speech available in English for the families of the crew who were in attendance.

Mister Burgmaster, Municipal Magistrates, dear families, officials from the R.C.A.F., WWII veterans, Forces representatives, ladies and gentlemen. As you have emphasized in your address, Mr. Dubuc, we are gathered here to honor these gallant airmen. Paying them the tribute they so highly deserve on the very spot where they met their fate. For those young fellows, not only came voluntarily from a very far away country, beyond the great waters, but they wanted to be part in the struggle, they personally could have ignored, against the nazi evil. The outcome of which, for us Belgians as well as for millions of other human beings, meant freedom or slavery.

As a crew, they belonged to the 434 bomber squadron of the R.C.A.F. stationed in those days in Great Britain. On board their Halifax airplane, they were en route for a bombing raid into very hostile territory. Alas, they never reached their target, fate had decided otherwise, brutally cutting short their young lives, in the skies above us.

You, dear families of those heroes, accompanied by the sole survivor of this odyssey, Mr. Herbert Brown, made the journey from your respective homelands, above all to express, with grief, personal homage to your loved one’s memory. For you Mr. Brown, by your presence at this ceremony, you pay a moving tribute to your comrades in arms, forever gone up yonder.

However, and thus honored by your sole presence, you also came for the inauguration of this remarkable commemorative stele, dedicated to this gallant crew, and which we owe to its tireless, talented and dedicated creator, Mr. Hector Maurage, whom, on your behalf and in my own name, I salute, congratulate and heartily thank. We are also grateful to Couvin’s Municipality, as well as Florennes’ Air Force Station Commander, who gave assistance to Mr. Maurage’s compelling, elaborate and time-consuming task.

Now, having performed our ceremony of remembrance, with your permission, I would like to take this opportunity to present to this assembly an outstanding Belgian wartime figure, who despite getting on in age, gracefully insisted on attending this remembrance ceremony. I cite Mr. Leopold Heimes. In order to stress the feats of this remarkable, but so discreet personality, one must go back over sixty years and remember the “Battle of Britain”, July 10th to October 31st, 1940, the outcome of which, in our favor, changed the course of history and saved humanity. Alas, Sir Winston Churchill, bless his soul, then Britain’s P.M. paid tribute to these British and Allied airmen who so gallantly and devoutly faced the onslaught of the German’s powerful Luftwaffe, with his historic words; “Never in the field of human conflict, was so much owed by so many to so few.” Well, not only, Mr. Heimes IS one of those few, but he is also the VERY LAST SURVIVOR of the 29 Belgian airmen who so brilliantly took part in the “B-of-B”. Thus, it is a great privilege for us all that he is amongst us today, for his presence enhances the homage we are rendering these brave Canadian airmen, whose destiny ended tragically on that night of December 1944.

To conclude, let us say that it is most imperative that we all bear in mind, and I particularly aim at our youth, that it is the courage, determination, devotion and sacrifice of all those who so eagerly fought the enemy during those dark hours, amongst whom the crew we honor, Mr. Heimes and Mr. Brown, which allows us today to enjoy peace, freedom and democracy. Lest we forget.

Note – They were mistaken in believing that Bert Brown would be attending the ceremony.

(3) Brian Hart spoke to the participants on behalf of the relatives of the crew. He made the following remarks in French: The families and relatives of the six Canadian fliers who lost their lives here so many years ago wish to thank the people of Couvin for honoring them here today with this monument and ceremony. We thank you for remembering them; their courage, their commitment and their sacrifice. They were young men. They were from across the great land of Canada, from farms and cities. They came to Europe and left behind their childhood dreams and loved ones to do what they must do because they believed in the cause. Thank you for remembering when it would have been so easy to forget. I remember We remember Always

The Beautiful Place

The Beautiful Place

The beautiful place - A valley in Belgium.

But evil was there - Families must leave.

The beautiful place - Bruly de Pesche.

But evil was there - In Hitler’s camp.

The beautiful place - Light, delicate leaves.

But evil was there - In his dark plans.

The beautiful place - Rain watered forest.

But evil was there - In the pool for his feet.

The beautiful place - Gentle green growing.

But evil was there - In bunker ugly and grey.

The beautiful place - Candles comfort the weary.

But evil was there - In his map room wicked.

The beautiful place - Balm for the heart.

But evil was there - Shrinking the soul.

The beautiful place - Softly, quietly, feel it.

But evil was there - Quickly! Away!

The beautiful place - Bruly de Pesche.

But evil was there - We cannot forget.

The beautiful place - A valley in Belgium.

Dale Plante

June 2005