by William C. Baldwin

Although D-day gave the western Allies a beachhead in northern France, it took them almost two months of bitter fighting to break out of the Normandy hedgerows. After the breakout, Allied armies raced across France, liberated Paris, and headed toward the German frontier. The rapid pace of the advance placed a severe strain on Allied logistics, which, along with bad weather and stiffening German resistance, slowed the offensive. By mid-December, American armies had reached the Roer River inside Germany and the West Wall along the Saar River in eastern France. Between these two fronts lay the Ardennes, a hilly, densely forested area of Belgium. The Germans had attacked France through this supposedly impassable region in 1940.

In early December 1944, five American divisions and a cavalry group held the 85-mile-long Ardennes front. The difficult terrain ofthe region and the belief that the German army was near exhaustion had convinced the Allied commanders that the Ardennes sector was relatively safe. Thus, three of the divisions were new, full of green soldiers who had only recently arrived on the continent; the other two were recuperating from heavy losses suffered in the bitter fighting in the Huertgen forest farther north. In addition, the heavy demand for American troops in some sectors had forced Allied commanders to lightly man other portions of the front.

After months of retreat, Hitler decided on a bold gamble to regain the initiative in the west. Under the cover of winter weather, Hitler and his generals massed some 25 divisions opposite the Ardennes and planned to crash through the thinly held American front, cross the Meuse River, and drive to Antwerp. If the offensive succeeded, it would split the British and American armies and, Hitler hoped, force the British out of the war Before daybreak on 16 December 1944, the German army launched its last desperate offensive, completely surprising the American divisions in the Ardennes.

One of the new divisions there was the 106th Infantry, which had relieved the 2d Infantry Division starting on 10 December. Its organic engineer combat battalion, the 81st, had begun road repair and snow removal in the division’s sector. Behind the 81st was the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion (ECB), a corps unit, which had been operating sawmills and quarries. The massive German assault on 16 December quickly interrupted these routine tasks. Both battalions found themselves fighting as infantry in a brave but ultimately futile attempt to stem the German offensive.

The Ardennes

On the morning of 17 December, as German troops were cutting off and surrounding the regiments of the 106th, the division commander ordered Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J.

Riggs, Jr., the commander of the 81st, to establish defensive positions east of the important crossroads at St. Vith. Reinforced by some tanks from the 7th Armored Division, elements of the two engineer battalions under Colonel Riggs held their position against determined German attacks until 21 December. During that afternoon, a heavy German assault, led by tanks and accompanied by intense artillery, rocket, and mortar fire, overran the exhausted American defenders. Colonel Riggs ordered his men to break up in small groups and attempt to escape to the rear. The Germans captured most of the survivors, including Colonel Riggs. For its participation in this action, the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion received the Distinguished Unit Citation, which praised its “extraordinary heroism, gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps.”

The capture of Colonel Riggs began an odyssey which eventually ended with his return to his battalion several months later. The Germans marched their prisoners over 100 miles on foot to a railhead. During that march, Colonel Riggs lost 40 pounds. From the railhead, Riggs went to a prisoner of war camp northwest of Warsaw. He escaped from the camp and headed for the Russian lines, surviving on snow and sugar beets. Late one night, the Polish underground discovered him, and he joined a Russian tank unit when it captured the Polish village where the underground had taken him. After some time with the unit, Colonel Riggs joined a number of former Allied prisoners of war on a train to Odessa.

From there, he went by ship to Istanbul and Port Said in Egypt, where he reported to American authorities. Riggs was eligible for medical leave in the States, but he insisted on rejoining his old unit, now in Western France. On his way back to the unit, Riggs stopped in Paris for a debriefing and made his first contact with his unit when he ran into some engineers from the 81st in a bar. It was their first news of him since St. Vith.

Other divisional and nondivisional engineer units found themselves in situations similar to the 81st during the first few days of the German offensive. As the American front in the Ardennes collapsed, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his subordinates redeployed their forces as quickly as they could to meet the German attack; but while these troops were moving into position, the American commanders had to rely on rear area troops already in the Ardennes. Many of these were corps and army engineer battalions, scattered throughout the area in company, platoon, and even squadsized groups. These small groups of engineers played important roles in the Battle of the Bulge.

Engineers sweep for mines in the snow during the Ardennes campaign.

Snaking their way along the twisted Ardennes road network, the German battle groups were bent on reaching the Meuse River with the least possible delay. As they advanced, U.S. Army engineers who had been engaged in road maintenance and sawmilling suddenly found themselves manning roadblocks, mining bridges, and preparing defensive positions in an effort to stop the powerful German armored columns.

A few examples will show how these engineers imposed critical delays on an offensive whose only hope for success lay in crossing the Meuse quickly.

Lieutenant Colonel Joachim Peiper, a Nazi SS officer, led one of the armored columns racing toward the Meuse. His route took him near the town of Malmedy and toward the villages of Stavelot, Trois Ponts, and Huy on the Meuse. Trois Ponts was the headquarters of the 1111th Engineer Combat Group, and one of its units, the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, had detachments working throughout the area. When he learned on 17 December of the German breakthrough, the commander of the 1111th Group sent Lieutenant Colonel David E. Pergrin, the 27-year-old commander of the 291st, to Malmedy to organize its defense.

Although most of the American troops in the area were fleeing toward the rear, Colonel Pergrin decided to hold his position in spite of the panic and confusion. He ordered his engineers to set up roadblocks and defensive positions around the town. During the afternoon of the 17th, engineers manning a roadblock on the outskirts of Malmedy heard small arms fire coming from a crossroads just southeast of their position. Shortly thereafter, four terrified American soldiers staggered up to the roadblock. They brought the first news of the Malmedy massacre in which Peiper’s troops murdered at least 86 captured American soldiers. Peiper did not attack Malmedy, but headed instead toward Stavelot where Colonel Pergrin had sent another detachment of the 291st. Equipped with some mines and a bazooka, the detachment delayed the column for a few hours. A company of armored infantry eventually reinforced the engineer roadblock, but this small American force was no match for the German panzers. Peiper’s column pushed through the village, and its lead tanks turned westward toward Trois Ponts.

Shortly before the Germans broke though the roadblock at Stavelot, Captain Sam Scheuber’s Company C of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion had taken up position in Trois Ponts. The 51st, also part of the 1111th Combat Group, had received orders to defend the village and prepare its bridges for demolition. While another detachment of the 291st wired one bridge south of the village, Company C, reinforced by an antitank gun and a squad of armored infantry, prepared its defenses. When Peiper’s tanks came into view, the engineers blew up the main bridge leading into the village. Although the river separating Trois Ponts from the German column was shallow enough for infantry to ford, it was an effective barrier to tanks. A detachment of German tanks headed down the river looking for another bridge, while other tanks and infantry remained behind, across the river from the village.

By the evening of 18 December, the small American force at Trois Ponts had come under the command of Major Robert B. Yates, executive officer of the 51st Combat Battalion, who had come to the village expecting to attend a daily staff meeting. Fearing that the Germans would discover the weakness of his force, Major Yates tried to deceive the enemy.

During the night, the six trucks of the engineer company repeatedly drove into Trois Ponts with their lights on and drove out with the lights off, simulating the arrival of reinforcements. The engineers put chains on their single 4-ton truck and drove it back and forth through the village to create the impression that there were tanks in Trois Ponts. An American tank destroyer, which had slipped off the road and into the river a few days earlier, provided the artillery. lt caught fire and its 105-mm. shells exploded at irregular intervals throughout the night. The ruses apparently worked, because the Germans never launched a determined attack on the village.

On 20 December, the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82d Airborne Division, which was trying to block the German penetrations, learned of the small force holding Trois Ponts. When the regiment moved into the village during that afternoon, Major Yates greeted its commander with, “Say, I’ll bet you fellows are glad we’re here!” American troops finally stopped and destroyed Peiper’s armored column a few days later; they had received invaluable assistance from the engineers who had delayed the Germans and forced them into costly detours.

Farther south, engineers were also caught up in the massive German attack. On 17 December, the VIII Corps commander ordered his 44th Engineer Combat Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Clarion J. Kjeldseth to drop its road maintenance, sawmilling, and quarrying operations and help defend the town of Wiltz in Luxembourg. The 600 men of the 44th joined a ragtag force consisting of some crippled tanks, assault guns, artillery, and divisional headquarters troops.

Attacked by tanks and infantry on the 18th, the engineers held their fire as the tanks roared by and blasted the German infantry following behind. Forced to retreat by the weight of the German attack, the defenders moved back into the town and blew up the bridge over the Wiltz River. By the next evening, the small American force was surrounded and running low on ammunition. The soldiers attempted to escape but few made it back safely. Among the heavy American casualties was the equivalent of three engineer companies dead or missing, but the defenders of Wiltz had slowed the German advance and given other American troops time to rush to the defense of the critically important crossroads some 10 miles to the west-the town of Bastogne.

With the American defenses collapsing west of Bastogne, the corps commander ordered the last of his reserves, the 35th Engineer Combat Battalion-a corps unit-and the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion-an army unit which happened to be working in the area-to defend Bastogne until reinforcements could arrive. On the morning of the 19th, German tanks attacked an engineer roadblock in the darkness. Unsure of his target in the gloom, Private Bernard Michin waited until a German tank was only 10 yards away before firing his bazooka. The explosion which knocked out the tank blinded him. As he rolled into a ditch, he heard machine gun fire close by. He threw a grenade at the sound, which ceased, and struggled back to his platoon. Private Michin, who regained his sight several hours later, received the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery under fire.

During the evening of the 19th and the morning of the 20th, the 101st Airborne Division, which had rushed to the defense of Bastogne, relieved the 158th and the 35th ECBs.

German panzers and troops continued to push west and north of Bastogne, eventually surrounding the American defenders in the town. These German penetrations threatened an American Bailey bridge over the Ourthe River at Ortheuville on the main supply route to Bastogne. Another combat battalion, the 299th, had prepared the bridge for demolition; and one of its platoons, reinforced by some tank destroyers on their way to Bastogne, was defending the bridge when German troops attacked early on 20 December. Alerted the previous evening to help defend the bridge, a platoon of the 158th arrived as German troops seized it. The platoon crossed the river and attacked the German flanks. By noon, the engineers and tank destroyers forced the enemy to withdraw. Reinforced by the rest of the 158th under Lieutenant Colonel Sam Tabet, the engineers held open the road to Bastogne for a few hours and allowed supplies of fuel and ammunition to reach the town. By evening, German tanks closed the road again and attacked the bridge at Ortheuville. In spite of mines the 158th had hastily planted on the road in front of the bridge, the tanks seized it. When the engineers attempted to demolish it, the bridge failed to blow up. Having delayed the enemy advance for a day and allowed some more supplies to reach beleaguered Bastogne, the 158th retired to the west to establish still more barrier lines.

A soldier from the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion checks a TNT charge during the Battle of the Bulge

Just a few miles to the southwest, engineers of the 35th Combat Battalion occupied positions blocking another crossing of the Ourthe River and, reinforced by an engineer base depot company, held off German tanks and infantry for most of the day. In the meantime, engineers to the rear blocked roads using minefields, abatis, blown culverts, and felled trees. When the Germans brought artillery to bear on the positions of the 35th, it retired under the cover of darkness, but only after imposing yet another delay on the German advance. The German panzer columns that broke through the engineer defenses on the upper reaches of the Ourthe River drove north and west farther into the American rear area.

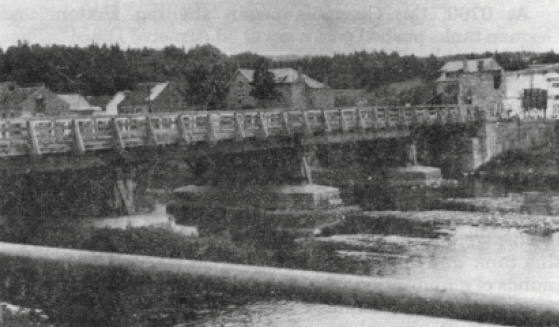

The 51st Engineer Combat Battalion defended this bridge over the Ourthe River, Hotton, Belgium.

At Hotton they encountered another Ourthe River bridge, a class 70 timber span, defended by engineers from the 51st Combat Battalion. After Company C had been ordered to Trois Ponts, the rest of the battalion under the command ofLieutenant Colonel Harvey Fraser established barrier lines in the area of Rochefort, Marche, Hotton, and from there a few miles f&her north. For the first few days, the engineers’ major problems were caused by the flow of American stragglers streaming to the rear and groups of German soldiers disguised as Americans. On the 20th, however, the forward positions of the 51st along the Our-the toward La Roche came under German attack, and by early morning on the next day, enemy armor reached Hotton. A makeshift force of engineers and others under the commander of Company B, Captain Preston Hodges, held the Hotton bridge. In addition to two squads of engineers, Hodges’ small force included a 7th Armored Division tank, which the engineers discovered in a nearby ordnance shop. They prevailed upon the crew to join in their defense of the bridge. More reluctant was the crew of a .37-mm. antitank gun, but Private Lee Ishmael of the 51st volunteered to man the weapon.

At 0700, the Germans began shelling Hotton, and German tanks pushed past a small 3d Armored Division force on the far side of the river. As a Tiger tank approached the bridge, Private Ishmael engaged it with his .37-mm. gun and Sergeant Kenneth Kelly attacked it with a bazooka. One .37-mm. round wedged between the turret and the hull, and as the smoke cleared, the 51st saw the German crew abandoning the tank. When two more tanks approached the American positions, the 7th Armored tank knocked one of them out and the other slipped behind some buildings near the bridge. An unidentified soldier volunteered to flush out this tank and crossed the bridge with a bazooka and two rounds of ammunition. Minutes later, Captain Hodges heard an explosion that sounded like a bazooka round, and the German tank slipped into View between two buildings. The 7th Armored tank fired into the opening, destroying the panzer. The tank-infantry battle raged into the afternoon, but the engineers held the bridge until reinforcements arrived from the 84th Infantry Division, one of the many Allied units now rushing to block the German penetrations. The 51st Engineer Combat Battalion continued to man roadblocks and hold bridges in the area until 3 January.

Throughout the Ardennes, divisional, corps, and army engineer units on the front lines and in rear areas participated valiantly in a sometimes desperate attempt to stem the tide of the unexpected German counteroffensive. After the American front in the Ardennes collapsed under the weight of the massive attack, few American units, except engineers, were prepared to resist. Engineer officers, like Riggs, Pergrin, Fraser, and Yates, insisted on staying in their positions, even when other Americans fled to the rear: Relying on their training in defensive operations, engineer troops established roadblocks with whatever troops and weapons were at hand, blew up bridges, planted minefields, and succeeded, often at the cost of heavy casualties, in delaying the powerful German armored columns. The delays that engineers helped to impose gave the Americans and British time to bring in reinforcements and seal off the German penetrations.

The Battle of the Bulge demonstrated that engineer initiative and training in defensive operations could make a major contribution to the outcome of an important campaign.

Sources for Further Reading

The best general account of engineers in the Battle of the Bulge is the chapter on the Ardennes in Alfred Beck, et al., The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Germany, United States Army in World War II (VVashington, DC: Center of Military History, 1985).

For a more detailed history of the battle, see Hugh M. Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, United States Army in World War II (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1965).

Janice Holt Giles’ lively story of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion’s exploits, The Damned Engineers, was originally published in 1970 and reprinted by the Office of History, Office of the Chief of Engineers, in 1985.

The same office resurrected an account of another battalion’s activities, written shortly after the events, from the files of the National Archives and published it in 1988 as Holding the Line: The 51st Engineer Combat Battalion and the Battle of the Bulge, December 1944-January 1945. The author was Ken Hechler, and Barry W Fowle added a prologue and epilogue.