Flight Lieutenant Joseph Philippe Suzor

by Willy Suzor

Joseph Philippe Suzor was born on the 9th of April 1909 on a small Indian Ocean island, “I‘le du Coin“, Peros Banos, and grew up in Diego Garcia, a dependency of Mauritius, where his father was an administrator for “Societe Huiliere Ile Maurice”. When the family returned to Mauritius, he went to “L’ecole Laval” for his primary studies and later finished his secondary schooling at the Royal College in Curepipe. He started a short stage in the police force, did not like it, and joined the Government Forestry Department. On a short trip to Reunion Island, he met and fell in love with a French girl, Raymonde Eaubelle. She joined him in Mauritius, and he proposed to and married her on the 16 of June 1941 only to volunteer to go to England three months later. As he never spoke about it, we will never know why he made such a decision, shortly after his wedding. He left for England with another volunteer, Philippe Ducler Des Rauches. On arrival on British soil, they both joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. The two Philippe’s remained best friends even after the war.

He enlisted on 16.9.1941 and was sent for an assessment by the RAF at the group training command station in Rufforth 1663, near Yorkshire, and was selected to become a navigator because of his mathematical skills. He was subjected to rigorous physical and mental tests which included training on the use of navigation tools, chart calculations, jumping by parachute, and physical fitness.

His RAF Id No was 135860.

By mid1943, trained and ready, he was commissioned to RAF Bomber Squadron 76 whose motto was RESOLUTE.

Squadron 76 base was at Holme-on-Spalding Moor.

One mission that left a lasting impact on him was the bombing of the German city of Cologne. Churchill had ordered Air Marshall Harris, of RAF bomber command, to bomb the Rhineland city of Cologne in retaliation for the German destruction of London. It was the heaviest air attack of the war. Using every available bomber at his disposal Air Marshall Harris dispatched 1000 bombers that night. Squadron 76 had twenty-one crews airborne led by squadron leader “Jock’ Calder.

For nearly 3 hours the city of Cologne was pounded by heavy bombs that penetrated deep down into the ground before exploding killing thousands of civilians trapped in the underground shelters. The incendiaries bombs took care of the ground level causing an inferno that resulted in the massive human loss of life and the destruction of the city. Churchill had his revenge, but the impact of knowing that the target was the civilian population of Cologne traumatized Philippe for many years afterward. He used to wake up at night covered in sweat following nightmares of that fateful evening.

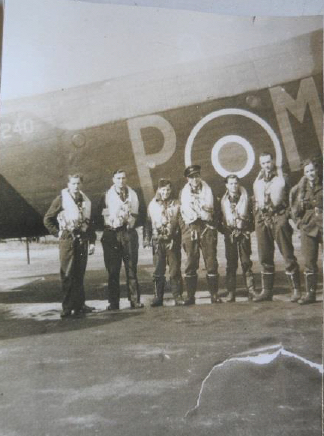

Xxx, J P Suzor, Jack Perry, E L Marvin, Arthur Thorp

Short accounts of pilot officer JP Suzor missions as recorded in conversation and in squadron 76 Operational bombing records.

References from JP Suzor RAF war records disclosure files and squadron 76 operational files.

Someone said that the life span of an RAF bomber crew member in 1943/1944 was 4-6 weeks.

Pilot Sergeant Alf Kirkham wrote (ref 3)

“There were some very fine men in 76 squadron and many of them died. It was rough in 1943 and one has to remember that the chances of finishing a tour were very remote, and what is more we did not really expect to.”

Pilot Major John Stene (ref 3)

“Somehow we managed to adjust to the situation and carry on in spite of the strain of seeing our friends and colleagues disappear, one after the other. We knew we had a job to do and we accepted the fact that we were ‘playing for keeps’ every time, we also knew the statistics and the odds for-or against-for survival. We often think back and remember all those friends whose luck ran out too soon.”

Philippe, as he was called by the members of his aircrew and ground crew, was the only officer amongst them, but despite his rank, he was very popular. Though only, he, was allowed in the officer’s mess, he made sure to join them in the local bar for a drink or two. He had to explain, on many occasions, about his unusual French accent, telling them that he was a descendent of French settlers that had come to settle in the then French colony of “Ile De France” later renamed Mauritius. The French lost the island to the English during Napoleon's reign. The act of rendition signed, allowed the French Mauritians to keep the Napoleonic laws and their customs. The British did not impose the English language upon them, though English was studied at school. He also had to show them, on a map, where Mauritius was situated in the Indian ocean because none of them at the time knew that the island existed. The members of the crew became a close team, very protective of each other and they knew that to survive they had to depend on one another, a band of brothers.

After the long arduous time of training, all preparations, and waiting, at long last, they were ready for their first bombing mission. It was on:

On 21 June 1943, the bombing of Krefeld. Halifax DK 201

The crew was given Halifax P with serial no DK201 in which they flew most of their future operational bombing missions. The Halifax was fitted with Rolls Royce Merlin engines. The Halifax was designed and engineered by Handley Page and manufactured by the Rootes company. They were designed to fly at high altitudes out of range from the enemy air defense. Due to the build-up of political tension in Europe, the British Royal Air Force ordered 100 Halifax bombers even before a prototype unit took flight. The Halifax bombers were built to be heavy bombers, featuring a large internal bomb bay with the possibility of carrying additional bombs in the wings. They first entered service with No. 35 Squadron RAF in November 1940 and conducted their first combat mission against Le Havre on the night of 11-12 Mar 1941. Veterans of Halifax bomber crews recalled how relieved they were, knowing that, flying at the high altitude the Halifax bombers could avoid German air defenses. However, they had the vulnerability of having a large blind spot beneath the back of the aircraft, which soon became a favorite angle of attack by German Luftwaffe fighters. The rear gunners complained about this defect and in 1943, changes were made to the design and the redesigned bomber entered service as the Halifax B Mk III. 2,091 of the modified versions were eventually built. In service with RAF Bomber Command, Halifax bombers flew 82,773 missions, dropped 224,207 tons of bombs, and lost 1,833 aircraft. They also participated, in other roles such as glider tugs, reconnaissance aircraft, and paratrooper transport.

The Navigator was responsible for keeping the airplane on its designated course at all times, guiding it to its bombing target and safely back to base. During the whole flight, a high level of concentration was required, mostly under strenuous conditions, which could sometimes be up to 7 to 8 hours.

The crew of Halifax DK201: Pilot Officer J. P Suzor, navigator, Sgt A.Thorp, pilot, Sgt G.A Barrell, front gunner/bomb aimer, Sgt J.F Perry, radio operator, J.T Zuidmulder, top gunner, Sgt T. Luder, engineer, Sgt E .L Marvin, rear gunner. Except for Sgt Marvin, who later got injured, the crew remained unchanged for the remainder of their bombing missions.

Airborne 23.56, Landed 04.04

With great anticipation, combined with nervous tension and not really knowing what lay ahead of them, though, they knew of the dangers of such bombing operations, they all were looking forward to their first mission. The flight to the target went without incident. The air defense was not effective. The bombing attack lasted one hour. Red and green targets dropped earlier covered the center of the town and before long the town was burning out of control under heavy bombardment. Incendiaries bombs were released at 2.07 and turned 9,000 acres of Krefeld into a raging inferno. It was a long and arduous flight that, for us, passed without any major incident. The first mission is done and dusted. We all went and celebrated with a few beers, though the celebration was subdued because from all the squadrons deployed there were heavy losses. 290 bombers were dispatched 43 failed to return, and 308 crew members' lives were lost.

22 June 1943 Bombing of Mulheim. Halifax V DK201

No sooner than the first mission was behind them, they were in a state of readiness for the next day's bombing of Mulheim.

Airborne 23.23, landed 4.58

The town of Mulheim was the target of this operation.

Attacked primary target at 1.43 from 20,000ft. Target identified by PFF markers. The bombs were released. The large concentration of fires with smoke rising to 8/9000 ft.

Despite the very thick cloud cover, the bombing caused substantial damage to the town. The squadrons deployed for this mission took heavy losses from heavy flack night fighters. Bomber command dispatched 557 bombers, 35 failed to return. We returned to base without incident. But we were all saddened by the loss of a very experienced crew led by Pilot officer J Carrie and Group captain D. Wilson an Australian who was the station commander.

Two days later the 24 of June 1943 Bombing of Wuppertal. Halifax V DK 201

The Elberfeld district of Wuppertal was the target.

Airborne 22.50, landed 04.06

Attacked primary target at 1.10 from 19,000ft. Target identified by PFF red markers. The bombs were released. The large concentration of fires. One large explosion was followed by a huge sheet of flame. Returned back to base without any major incident.

From all the squadrons, 630 bombers were dispatched, and 33 failed to return

During the two weeks break, the crew of DK201, used the time in between raids to conduct exercises over land and sea. The pilot would fly on two and three engines making sure in an event of engine failure he would have the experience to handle any emergencies. The pilot would also practice ‘Corkscrew to port” an emergency call from the rear gunner that will warn the pilot of an imminent attack from a night fighter. The pilot would immediately react by opening the throttles causing the aircraft to bank at 45 degrees, making a diving turn to port, and descending to 1000 ft in the space of six seconds reaching an airspeed of nearly 300 mph. The pilot would then pull the aircraft into a climbing turn to port. As the wing went down, the tail would come hurling up, and then the tail section was plunged back as the pilot pulled back on the controls causing the plane to climb steeply in the opposite direction. The flight path in the sky would replicate a coiling corkscrew configuration. The stresses on the airframe had to be monitored by the crew who had to withstand the resulting G forces. Incredibly the night fighters were thrown off and found the corkscrewing bomber a difficult target to follow. This evasive action saved many bombers from destruction.

9 of July 1943 Bombing of Gelsenkirchen. Halifax V EB240

Target the oil supply and the coal liquefaction plants and refinery for fuel production.

Airborne 23.00 Landed 05.24

We attacked the primary target in poor visibility at 01.36 hours from 20,000 ft. A large explosion was observed at 01.40 hours, and the refinery at Scholven was not completely put out of operation. Another long night even though the mission was not as successful as planned.

Bomber command dispatched 418 bombers dispatched, but 12 failed to return.

18 of July 1943 Bombing of Montbeliard. Halifax V EB240.

Airborne 22.06, Landed 05.55

Target, the Peugeot motor factory at Montbeliard on the outskirts of Sochaux, and the manufacturing plants for Tanks and transport vehicles were identified visually and attacked from 7,500ft at 1.56 hours. Bombs were successfully released in perfect visibility. The target was a mass of flame. The flight back passed without incident except for wing commander Don Smith who had to cope with the failure of both starboard engines. He ordered some of his crew to bail out and he was able to force- land in a potato field with the rest of the crew members who had no time to bail out.

27 July 1943 Bombing of Hamburg. Halifax V EB240

Air Chief Marshall Harris ordered 4 important bombing operations against the industrial city of Hamburg code-named Operation Gomorrah. The first raid started on the 24th of July. The plan was for the bomber command to bomb at night with high explosives and incendiaries and the American air force by day.

We were airborne at 22.32, Landed at 04.40

To avoid detection by the German grid radar system, we flew over the North sea. We made our approach from the North of the Elbe looking for PFF markers. Primary attack at 1.24hrs from 19,000ft. Identified by yellow and red markers. Fires still raging around markers. We released all our bombs. Active anti-aircraft with searchlights and had to wave off the night fighters that were out in force that night. For the first time we used and released thousands of predetermined lengths of metallic strips into the air to confuse the enemy radar detection, this ploy to confuse the air defense radar system was a success and saved lots of aircrew lives. 23 bombers from SQ 76 were dispatched and 1 failed to return. Sergeant Bjercke RNCAF, whose Halifax was crippled by relentless flack was finished off by a night fighter. There were five survivors who were later captured. They were only three weeks with the squadron.

Operation Gomorrah was successful, though it claimed 70 bomber crews from a total force of 740 bombers deployed for the mission. Hamburg was reduced to ruins and 40,000, mainly civilians were killed. Although we saw a lot of activity around us, we returned safely to base.

The next day the American Air Force flew two successful daylight bombing raids causing even more destruction to infrastructure and civilians.

10 August Bombing of Nuremberg. Halifax V DK 223

Airborne 21.47, Landed 05.16

Released bombs at 1.25 hours from 17,000ft over the target area. Though the German flack was heavy below us we returned from another successful bombing operation without incident. But Sergeant Troake and John Maze had close encounters on the Hamburg raids. They both showed great flying skills in order to evade the German night fighters.

12 August Bombing of Milan. Halifax V EB240

Airborne 21.03, Landed 06.15

Attacked at 01.25hours from 17,000ft. Encountered night fighters activity, but no action from our gunners.

The raid on Milan was very successful, the railway network, the Breda Steel, and locomotive manufacturing plant were badly damaged. Our bombs were accurately released upon the green markers. Fuel ran low and we had to land on an airfield an hour away from Holme. Two crews from our squadron were reported missing. Pilot Officer Mc Cann, on his 20th bombing mission, was shot down near Bemay in the north of France.

17 August Bombing of Peenemunde. Halifax V EB240

Bomber Command War Diary 17/18 August 1943, The Peenemunde Raid.

“596 aircraft – 324 Lancasters, 218 Halifaxes, 54 Stirlings. This was the first raid in which 6 (Canadian) Group operated Lancaster aircraft. 426 Squadron dispatched 9 Lancaster IIs, losing 2 aircraft including that of the squadron commander, Wing Commander L Crooks, DSO, DFC. This was a special raid that Bomber Command was ordered to carry out against the German research establishment on the Baltic coast where V1 and V2 rockets were being built and tested. The raid was carried out in the moonlight to increase the chances of success. There were several novel features:- there was a Master Bomber controlling a full-scale Bomber Command raid for the first time; There were three aiming points – the scientists’ and workers’ living quarters, the rocket factory, and the experimental station; The Pathfinders employed a special plan with crews designated as ‘shifters’, who attempted to move the marking from one part of the target to another as the raid progressed; Crews of No 5 Group; bombing in the last wave of the attack, had practiced the ‘time-and-distance’ bombing method as an alternative method for their part in the raid.”

Since 1942 strange activities on the island of Usedom, in the Baltic had attracted the attention of Allied intelligence.

The bombing of Peenemunde Halifax V EB 240 JP Suzor account, as related to his son, of that eventful evening.

Airborne 21.05 landed 4.33

Total secrecy surrounded the briefing for Peenemunde on the island of Usedom in the Baltic. At the briefing, we were told that if the target was not destroyed, we will be sent back until the mission is accomplished. Squadron 76 sent 20 bombers on an early wave A total of 600 aircraft were dispatched. Because of the mission perilous route, a raid over Berlin by 8 Mosquito bombers was planned in order to confuse the Germans as they scrambled their fighters to intercept the decoy Mosquitos. Because of the target size, the bombing height was changed from the usual 16,000ft to between 5,000 and 10,000ft. Bomber command chose a moonlit evening in order to increase the chances of success. The attack was well concentrated, lots of markers lit up the bombing area, as we dropped our bombs over the target at a height of 8,000ft. Large fires and huge explosions were noted. We encountered moderate to heavy anti-aircraft with searchlights but were spared from any problems. All 20 bombers returned to the air base without any major problems.

The German night-fighters that were deployed to Berlin to intercept the Mosquitoes bombers were redeployed to Peenemunde and caused a lot of casualties to the last few waves of bombers. We returned safely to base after being airborne for more than 5.50 hours.

20 0f August 1943 Bombing of Nuremberg. Halifax V DK 223

Airborne 21.47, Landed 05.16

We attack the primary target at 1.25 hours from 17,000 ft. identified the markers and dropped the bombs successfully. Returned to base without any incidents.

22 August 1943 Bombing of Leverkusen. Halifax V EB240

Airborne 20.57, Landed 02.16

Attempt to hit the chemical plants at Leverkusen, was not a great success. The markers were barely visible and we were hampered by thick banks of black clouds which hung motionless over the bombing target. Dropped the bombs at 0016 from 19,000ft hoping that they will hit something of importance.

23 August Bombing of Berlin Halifax V EB240.

Airborne 20.17, Landed 05.10

Unlike the previous day, the evening was clear of clouds as 700 bombers pounded Berlin. Few crews experienced any major problems, and the target points were well marked and identified. Attacked commence at 00.16 from 19,000 ft. Because of the heavy concentration of airplanes the pilot had to keep a close watch in order to avoid a mid-air collision. We noticed fires blazing over large areas. The city’s defenses were well organized and well prepared, and the resultant flack was intense and hostile. Amazingly only two-night fighters, Luftwaffe’s experienced Nachtjager as they were known, tried to intercept but did not cause any major trouble.

27 August 1943 Bombing of Nuremberg. Halifax V EB240.

Airborne 20.57, Landed 04.53

23 crew took part in an attack on Monchengladbach, a town lying on the outskirts of the Ruhr west of the Rhine but only seventeen reached the target. Bombing conditions were not ideal. A layer of cloud covered the Ruhr and to make matter worse, the main bombing force had to contend with a lack of target markers. We attacked at 00.39 from 18,000 ft. Many crews released their bomb load too early and it is doubtful if any major damage was caused. The Luftwaffe night fighters were up in some numbers and caused some casualties and damage. We were attacked and hit by tracer bullets, no one was hurt and we managed to get back. The squadron leader Stuart crashed with his plane after being pursued and hit by tracer bullets from a night fighter.

31 August Bombing of Berlin. Halifax V DK149.

Airborne 20.14, Landed 22.29

JP Suzor flew with a different crew for that mission replacing the navigator who reported sick.

Operation abandoned. Starboard's outer engine failed after take-off. Bombs were jettisoned

From 1500ft at 20.31 hours.

5 September 1943 Bombing of Mannheim. Halifax V EB240

On Sunday the 5th of September, 600 aircraft took part in the bombing of the chemical and armament industries of Mannheim. SQ 76 provided 20 bombers for the operation. According to RAF record, Pilot Officer J.P. Suzor and the crew, Sergeant A. Thorp, Sergeant J.T. Zuidmulder, Sergeant J.F. Perry, Sergeant G.P. Barrell, Sergeant E. Luder, Sergeant E.P.L. Marvin of the Halifax bomber EB240 arrived back at 3.19 am, from a bombing mission on Mannheim. They

had a torrid time with stubborn night fighters. In the ensuing battle with a German fighter, pilot Throp screamed at the top gunner to watch out as he tried to “corkscrew”, but the Halifax was hit. The landing gears were damaged and the fuselage was riddled with holes from tracer bullets. Someone shouted that the rear gunner sergeant Eric Marvin was badly injured. He had serious leg and hand injuries. Rear air gunner Eric Marvin was a vigilant and resolute member of the crew. During the battle with the German fighter, who attacked from below and then from behind, Eric was able to line him in his sights and fired all four guns, hitting the German plane, but not before the German fighter pilot fired a cannon shell which sheared through the floorboard of the rear turret and exploded as it hit the control column of the Browning guns. What followed at the rear of the Halifax was of the highest level of bravery. Eric was hit in both hands, wounded over his left eye, and suffered a bullet wound in his left leg. Disregarding the pain, he continued firing his guns at the German fighter who gave up the chase with a badly damaged aircraft. Sergeant Marvin bleeding profusely from his wounds scrambled out of his turret. His oxygen mask has been torn off. Using his elbows, he managed to crawl towards an oxygen tube before being helped by a crew member. Inside the Halifax, I became aware of the seriousness of the situation and rushed to the back of the bomber to help. We were able to control the bleeding. The pilot Thorp, again shouted to the upper gunner, Zuidmulder, to look out for the German fighter, unaware of what was happening at the rear of the bomber, that the rear gunner was seriously injured and that he had most probably destroyed the enemy aircraft. Eric Marvin displayed great courage and bravery in face of adversity. No one else was seriously injured. With no hydraulics to release the landing gears, Pilot Arthur Thorp successfully crash-landed at Ford airfield in Sussex. No further information is available for this event. Because of his injuries, Sergeant Eric Marvin never flew again. During his recovery in the hospital, he received surgery for his wounds, and his left eye was replaced by a glass one. Eric Marvin went back to his electrical trade and served with 587 squadron, an anti-aircraft unit. For his courage and bravery, the commanding officer of Squadron 76 sent a recommendation for a medal to the chief of bomber command, Sir Arthur Harris. Eric was the proud recipient of the Distinguished Flying Medal.

Ref from the book by Colin Pateman “Glorious in solitude”

Wing commander, commanding No 76 squadron RAF.

Date 5 April 1944. Remarks by station commander.

“Sgt Marvin displayed extreme and outstanding courage. In the face of heavy odds, he continued to fire at the enemy, and although badly wounded, he did not leave his turret until the enemy fighter had disappeared. His cheerful courage throughout his trying ordeal was a fine example and inspiration to the rest of the crew and the other members of the squadron. I consider his outstanding conduct fully deserves the immediate award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.”

Eric Marvin died on the 9th of May 1976, aged 60.

15 September 1943 Bombing of Montlucon (France). Halifax V EB253

The rear gunner was replaced by Wilkie Wanless from Royal Canadian Air Force. Wilkie, because of circumstances unbeknown to him, had flown with different crews as a spare rear gunner. He was very experienced having flown many bombing operations and he was happy to join the crew he got on well with all the members.

Airborne 20.12 Landed 02.59.

A successful strike against the Dunlop factory works at Montlucon, 45 miles northwest of Vichy. This attack, we believe, was a stunning blow to the Germans as we watched billowing smoke rising up to 8000 ft. Attacked at 23 .41 hours from 5,500 ft. The glow of fires was seen 70 miles away on the return journey.

16 September Bombing of Modane. Halifax V DK201.

Airborne 19.55, Landed 23.27

Mission aborted. Fuel leak between the long-range tanks and the wing tanks.

27 September 1943 Bombing of Hanover. Halifax V DK201.

Airborne 19.07, Landed 00.50

Attacked primary target at 22.02 from 18,000 ft. Escaped from an attack from a JU 88. The Bombing was well concentrated, and we inflicted heavy damage to the city as we watched fires burning over a wide area. The squadron experienced heavy losses from night fighters. We had a harrowing encounter with a night fighter and the upper gunner reported several holes in the fuselage. No one was injured.

29 September 1943. The bombing of Bochum. Halifax V DK201

Airborne 18.21, Landed 23.18

Attacked at 21.00hrs from 18,000ft. Concentrated attack around the markers. Returned to base without major incident.

3 October 1943. The bombing of Kassel. Halifax V DK201.

DK 201crew members were briefed for Kassel. Date 3 Oct 1943, place Squadron 76 base at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. Pilot officer and navigator Joseph Philippe Suzor ( from Mauritius) was the senior officer on board, Officer Arthur Thorp was the pilot, sergeant Jack Perry the radio operator, sergeant Ted Luder the engineer, William “Wilkie” Alexander Wanless(Canadian) rear gunner, J.Zuidmulder mid-upper gunner, G.P.Barrell and K.D.Butters. Primary target Kassel: The mission was the bombing of the Fieseler aircraft plant, the Henschel works, the manufacturing town, and the key railway lines. The vast Henschel works, are situated at Mittefeld in the northwest outskirts, Rothenditmold on the western edge of the city, and the Werke Kassel. These plants were used for the manufacturing of locomotives, Tiger tanks, Anti-tank guns, and spares.

J P Suzor's account of this eventful evening is related to conversation with his son.

Wing commander Don Smith led the squadron of 20 crews. Our crew of Halifax DK 201 was the most experienced having flown on more than 17 successful and eventful missions. It was a moonless evening as the Halifax's four Merlin engines roared and disturbed the stillness of the night. Pilot officer Thorp pulled back on the control stick and we took off, direction Kassel. The time was 18.08. I went about my navigator’s task thinking that it would be another long night. I had my Mercator’s chart laid out with the ground plot and air plot on it. With that information, I could plot the route and direction quite accurately.

When we reached the target area, we noticed that the town and surrounding areas were pounded by heavy bombs which caused considerable damage. The German night fighters came out in force that evening and we had to take some evasive action. Both the upper and rear gunners saw a lot of action.

During the diversion with the night fighters, we flew past Kassel. We turned and came back towards the target. Out of nowhere appeared a German fighter (refer to note 1) no one saw him as he fired his tracer bullets which sheared through the fuselage, killing the mid-upper gunner J.Zuidmulder and hitting the starboard wing. The Halifax DK 201 became a ball of fire. My oxygen had been cut off. The pilot, Arthur Thorp, tried in vain to control the plane's downward plunge. We were now in an uncontrollable spiral dive and we had to scramble out of the doomed plane as quickly as possible. Gasping for air, I frantically opened the hatch next to the navigator table and threw myself out of the plane praying that I was not going to be hit by debris or another plane. The last one out was W. Wanless, (RCAF) the rear gunner. Why the pilot Arthur Thorp did not bail out as he went down with the plane remains a mystery. “Wilkie” Wanless later reported that he spoke to him just before bailing out of the plane and he seemed ok.

The freezing air jolted me back to face the situation. I counted to 3 and prayed that my parachute would open as I pulled hard on the releasing strap. I felt a jolt and was whisked upwards, stabilized as the chute fully deployed and slowly parachuted towards the ground whilst thanking the good Lord. In the distance, I could see the fire burning and the roaring of the bomber’s engines in the distance. Slowly I descended to the ground. It was a dark moonless night and could not judge how high I was until I crashed into a tall pine tree and slid unhurt down the branches. The top of my chute cupped the tree top as I came to a sudden halt. Not being able to judge how high up the tree I was, I decided to wait until dawn. At first rays of sunlight, I looked down and to my surprise noticed that I was only a couple of meters from the ground. With my RAF-issued knife, I cut the straps and decided to find a hiding place. I lay low during the day and walked at night. Unfortunately, because of low visibility, I could not walk fast. I hid again the following day and whilst in a deep sleep, I was abruptly awoken by two German soldiers screaming at me with their guns pointing directly at my chest. I was marched to the nearest German camp. The Gestapo questioned me “Remember to tell them nothing, but your name, rank, and number”. After establishing that I was an RAF officer they locked me up in the city’s jail. A few days later I was taken by train for further interrogation at the Dulag Luft located near Frankfurt. It was the Luftwaffe interrogation center where all captured airmen were sent after capture for interrogation. I just gave them my name, rank, and number and divulged nothing else. Frustrated, they threw me into solitary confinement. A few days later, I was sent with a group to Poland as a P.O.W and incarcerated in Stalag Luft 3. I arrived there on the 17 of October 1943.

Allied aircrew shot down during World War II were incarcerated after interrogation in Air Force Prisoner of War camps run by the Luftwaffe, called Stalag Luft, short for Stammlager Luft or Permanent Camps for Airmen. Stalag Luft III was situated in Sagan, 100 miles south-east of Berlin, now called Zagan, in

Upper Silesia, Poland

(The camp was made famous internationally by the book and film “The Great Escape”

Note 1 (Reference)

Luftwaffe claim. Ref “Nachtgagd war dairies” Vol 1 by Theo Boiten.

“Kill claim of DK201 Sq76 Halifax by Hptm Hans Baer 4/NJGB Halifax Northwest of Kassel at 4,5000m at 22:06 3rd of October 1943.”

DK 201 crashed near Lenstrup close to Detmold. Both the pilot Arthur Thorp and upper turret gunner J. Zuidmulder are buried in the Hannover War Cemetery. Thorp plot 12.H.3, Zuidmulder plot 12.H.2

Four Halifaxes were lost that evening, DK247, LK904, DK203, and DK201, the worst Squadron 76 casualty in a single operation. A total of 16 crew members of Squadron 76 died in this operation.

No detailed account regarding Philippe Suzor’s time in the Stalag Luft 3 camp is available but he did mention that food was scarce, and they had to rely on the Red Cross to provide them with survival amenities. They lived in barracks and for most of the time had freedom of movement around predetermined perimeters. The winters in 1943 and 1944 were also very harsh and tested their will to survive. His biggest fear was that he would get an attack of malaria, a disease he had contracted in Mauritius. That could have meant certain death, but thankfully he had no recurrence of the disease whilst in the camp. The event of 24 0f March 1944 when 200 airmen attempted to escape through a tunnel left an air of excitement within the camp. (The story is depicted in the movie “The Great Escape”. The film did not impress Philippe as it was a combination of fiction and fact. The escape plan was to dig 3 tunnels code named Dick, Tom, and Harry. The tunnels were dug to a depth of 9/10 meters and then leveled towards the forest outside and beyond the perimeter of the camp. Because of the sandy soil condition, it was deemed too dangerous to dig Dick and Tom. They had to be abandoned but Harry went ahead. On the 24 of March 1944, the 200 selected airmen were ready to escape. The plan was meticulously prepared, but unfortunately a German guard on duty that evening spotted an escapee as he emerged from the tunnel. By then 76 of the airmen managed to escape. They split into 3 groups, traveling by rail and on foot. Unfortunately, after a few days, they were recaptured. Only 3 airmen, one Dutchman, and two Norwegians managed to get back to safety. Enraged by the news that so many had escaped, Hitler, Himmler, and Goering collectively gave the order to the Gestapo to execute all the recaptured airmen, a complete violation of the Geneva convention regarding escaped prisoners of war. In groups of two and three and at different times 50 of them were executed, including Squadron leader Roger Bushell the mastermind behind the planning of this daring escape. Upon hearing of the massacre, the whole camp was in a state of shock, sadness, and hate toward the Germans.

Early in April 1945, the Russians were only 16 miles east of Sagan. Hitler had ordered that all American and British officers be moved or evacuated to the west towards Stalag Luft VIIA. In the turmoil that followed, Philippe and a South African, Willem Botha nicknamed “Corra”, decided to escape even though the Germans guards had strict orders to shoot anyone trying to escape. Walking at night, when moonlight permitted, hiding and walking during the day, they were hoping to meet with the advancing allied troops. Hungry and thirsty they arrived at a farmhouse and with hand gestures, the old German farmer understood what they were after. The farmer’s wife gave them each a glass of milk and a couple of boiled potatoes. They quickly ate and drank and hurriedly departed. One cannot, but wonder, what would have been the farmer’s reaction if it was during the early years of the war. They later met with an advance group of American soldiers, on a reconnaissance patrol, who advised them on how they could join the American forces of General Patton.

On the morning of April 29, 1945, the 14th armed division of Patton’s 3rd army attacked the SS troops guarding Stalag VIIA.

He was happy to hear about the success of the allied army's advance into Germany. On his return to England, because of his medical condition of malnutrition and disease on his scalp (Sebboheric dermatitis), he spent time in a medical facility. Once he regained some strength, he was de-briefed by the authorities, upgraded by the RAF to the rank of Flight Lieutenant, and allowed to return to his family in Mauritius.

The RAF then gave him the command of Plaisance airport which was under the Royal Air Force jurisdiction. In 1942, when Mauritius was a British colony the government decided to build a small airport at Plaine Magnien near Mahébourg. The airport was used as a military base for the Royal Air Force during the Second World War.

His wife, thinking that he was “missing in action and presumed dead” from a telegram sent to his family in Mauritius by the RAF Bomber Command in October 1943, had returned to Reunion Island, and met a French man, and lived in Madagascar. Philippe met with her and later agreed to a divorce.

On 12.4.1946, the RAF commissioned him to take command of the RAF base in Mogadishu, then Italian Somaliland. While there, he met and later married Franca Bonetti on the 12 of August 1947, an Italian woman, whose family had moved from Italy to Mogadishu to start a transport business. After his stage in Mogadishu, he returned to Mauritius with his Italian bride.

He was demobilized in 1948 and remained a commissioned RAF officer until 9/4/1954. He rejoined the Forest Department and was given charge of the southern part of the Island. He indulged in his hobbies of woodworking, listening to Classical music, reading, hunting, and fishing. He retired early, and immigrated to Johannesburg South Africa with his wife Franca and his two sons Willy and Mario. He died in Johannesburg on the 30th of December 1995 at the age of 86.

He remained a true Mauritian throughout his life and his love for his island was never waived. His ashes are buried in a family grave at St Jean’s cemetery in Mauritius.

The Air Crew Europe Star Campaign medal of the British Commonwealth was awarded to J P Suzor for service in World War Two. This medal was awarded to Commonwealth aircrew who participated in operational flights over Europe, from UK bases, or for operational flying from the UK over Europe, between the 3rd September 1939 and the 5th June 1944. As with most Armed Forces Serving Personnel during the conflict of World War Two, J P Suzor was entitled to the War Medal 1939-1945. This medal was awarded to all full-time service personnel. J P Suzor was also awarded the 1939-45 Star for operational Service in the Second World War between 3rd September 1939, and 2nd September 1945. He was also awarded the Defence Medal (British Commonwealth and Empire medal for service during world war two.)

Flight Lieutenant Joseph Philippe Suzor qualified for the following medals:

1. 1939-1945 Star

2. Aircrew Europe Star

3. Defense Medal

4. War Medal 1939-1945.

5. Caterpillar club membership card

Having saved his life by parachute he was a proud member of the famous “Caterpillar Club”.

Reference list

R.A.F Declassified Operations Record Book, Detail of Work Carried Out by No. 76 Squadron

RAF Disclosure declassified war records of Flight Lieutenant J.P Suzor.

Chorley, W.R, (1981). To see the dawn breaking. Longton, Preston: Compared Graphics.

Supplement to the London Gazette 28 April 1944

Pateman, Colin, 2013, Glorious In Solitude. Fonthill Media Ltd

Pilot Officer (Pilot) Arthur A Thorp

Age 20?

|

Son of Aaron and Jessie Thorp of Yeldersley, Derbyshire Death: |

Oct. 3, 1943 |

|

Inscription: Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve Note: 156078 |

|

|

Burial Hanover War Cemetery Hanover Hannoversche Landkreis Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen), Germany Plot: 12. H. 3. |

|