Quite a story. Thanks for sharing it with me."

I WAS FIRST ON D-DAY

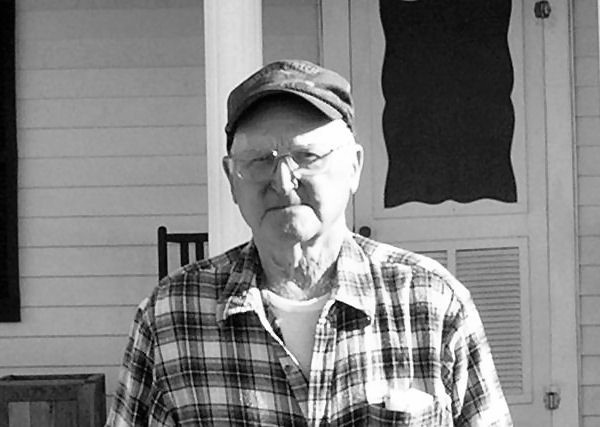

by Sgt. J. L. Doolittle

of Edgefield County, South Carolina

as told to and written by Rev. Dan White Appling, Georgia

"Quite a story. Thanks for sharing it with me."

- Retired General Perry Smith USAF

Secretary, Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to retired Air Force General Perry Smith, Secretary, Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation, for his invaluable help in clarifying Army units and commanders in J. L.'s story as I placed J. L.'s story in its historical World War II context. Thank you, General Smith for taking time to edit this story for historical accuracy.

I am also grateful for my wife, Joyce, whose encouragement to write not only J. L.'s story but to also continue my pursuit of writing is the wind in my sails.

I would also like to thank the good people of Red Oak Grove Baptist Church whose response to the publication of this little book has been most gratifying to both me and to J. L. and his family.

Finally, I am grateful to the Old Edgefield District Genealogical Society and their President, Douglas Timmerman, for making copies available to their members and to the public. J. L.'s story deserves to be read by all.

- Rev. Dan White

A paid vacation

The War in Europe was over. I was in Czechoslovakia in June of 1945 and eating supper. Someone shouted, "Hey Doolittle! Would you like to have a paid vacation?" "Boy, would I!" I shouted back. "Well, you've got about ten minutes to catch the next jeep outta here!"

"I'll catch it in five!" I took a plane out of Czechoslovakia and flew back to England where the D-Day invasion had begun.

From England, I returned to the United States at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, where I had received extensive training for the invasion. The Army issued me new clothes. I had accumulated more than enough points to get out. I was discharged on June 22, 1945.

During the war, there were two things I got to wanting. I wanted a Coca-Cola and an ice cream.

As soon as I got to the States, I drank a Coca Cola and ate an ice cream. It put me in the hospital, and I just about died. All that I had had to eat during the War was "K" rations for just over six months. The Coke and ice cream just about did to me what the Germans couldn't do!

I took a bus back to Edgefield, South Carolina, from New Jersey and arrived in the middle of the night. Mom and Dad lived in the country—about ten miles or so from Edgefield, and I had no ride to take me back home. So, I asked the bus driver if he could take me on to

Augusta. There, I woke up a friend and asked him to take me home.

Mom and Dad did not even know I was back in the States. I walked in the door at four in the morning. Mom thought that I was my brother, Cleveland, and hollered out, "Cleveland is that you?"

"No mom, this is J. L."

Mom and Dad came running out of their room and they hugged me and cried tears of joy. I'll never forget it.

Mom didn't know that I had been a Commando in the D-Day invasion for national security reasons. It was a while before I could even tell them about it. I just couldn't talk about it. If a plane flew over the house at night, I'd come straight out of my bed and duck for cover. It's hard to talk about it a half century later. It still bothers me even now. I still don't like talking about it.

War is against everything that I was taught by my church,1 my parents, and the Bible. To have seen my friends die and to see young Germans die who didn't want to fight any more than I did troubles me to this day. The newspaper wanted to interview me when I got back from the War, but I couldn't talk about it. Since then, I have tried to forget a lot, and I have forgotten a lot. I'm telling you things today that I've never told anyone else.

We seem to have a whole generation of young people coming along who don't know the cost of freedom. They either have forgotten or don't know the price me and millions of other American soldiers paid for freedom. I hope my story will help them to know and remember not only what I went through but what all men and women went through who have served our country. Their sacrifices and the blessings of God upon our country preserve our freedom.

I enlist in the Army

In the winter of 1940, one year before Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, my oldest brother, Cleveland, was drafted into the Army. I was twenty-one and had been working at King's Mill in Augusta since I was fourteen.

During the day, I'd plow a mule and then work at the mill on the second shift from three in the afternoon to eleven at night. I decided to enlist in the Army to be with my brother. When my mother found out that I had volunteered for the Army, she pitched a fit! She begged me not to go into the Army, but I told her that I had already signed the papers. It was too late to back out. The odd thing about all this is that they eventually turned my brother down because he had asthma, but they didn't find anything wrong with me!

Training for the D-Day Invasion

After basic training at Camp Croft in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Ft. Dix, New Jersey, I was involved in a wreck in Massachusetts that landed me in the hospital. An Army truck I was riding in went over a cliff. As a result, I was transferred and stationed at Fort Benning near Columbus, Georgia. Back then, Army enlistment only obligated a soldier to serve for one year. I had served my time and was preparing to be discharged on December 8, 1941. But, the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on December 7 meant that no one would be released from the Army. We were at war.

"I was sent to Ft. Gordon near Augusta, Georgia, to begin amphibious training.

I was hand picked to be a member of this unit called the Commandos2 which was an elite unit of the Army Rangers. In order to be a Commando you could not be taller than 5 feet and 8 inches and could not weigh more than 160 pounds. You couldn't be married. After watching and evaluating me during our swimming and hiking exercises, I was chosen to be a Commando. Of course, I didn't know what was going on. I only wanted to do my best.

J. L. chuckles and said, "If I had known what I know now, I might not have trained quite as hard!"

I would much later learn that our Commando mission would be to prepare the way for the main invasion of the Normandy beaches. Our mission was to clear the water of mines and barbed wire so that others could follow.

"We spent some time at Ft. Jackson, near Columbia, South Carolina, training with amphibious trucks at Ft. Jackson. Those trucks were a disaster because they would not float in the water. The Army quickly canceled that project!

"We were also sent to Ft. Pierce, Florida, just south of Daytona Beach. We camped on an insect-infested island and practiced small-scale amphibious raids with rubber boats and similar craft. We had to swim a mile without a life jacket. We were promised a fifteen day leave if we could do it. Being a country boy who loved to swim in the ponds and creeks back home, I did it the first time and was allowed to come back home for a two week break. "Our training in Florida was intense but fun. It was during the winter and was a lot warmer there than it was in Augusta. We trained with the Navy Sea Bee's and were taught to blow up razor wire with pipe bombs out in the ocean. That stuff could really cut you.

"After training in Florida, we were sent to Ft. Dix, New Jersey, and arrived on November 20, 1943, for training in advanced tactics. That was our last stop before deployment overseas.

"The final preparation was intense. There were speed marches and more intensive training in all phases. We trained at Ft. Dix until December 20, 1943. Then we moved to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, which was our port of embarkation to England. All the time, officers and soldiers were being weeded out from our group. They wanted us Commandos to be physically and mentally fit in every way."

"During my Commando training I got to know the men in our unit. When we were up North, I visited in their homes, and when we were at Ft. Gordon, they came out to my home. We knew each other's families and just about knew each other's thoughts. I knew when they were up or down. I knew their parents and they knew mine. After training together for almost three years, we became close friends. It was my close friends who suffered and died on Utah Beach at Normandy on June 6, 1944."

J.L.'s Commandos were an elite group within the Ranger Battalion. These World War II Rangers were the first to be trained and deployed in the history of the United States Army.

I Arrive in England

"We landed in England on February 8, 1944." In England, J. L. received further training in small crafts for night landings and drilled in all forms of reconnaissance and combat techniques.

Orders for J. L. and his battalion arrived on April 2nd to move to the Army assault training center at Braunton, England. It's coast was similar to the coast of Normandy and made it an ideal location to train for the assault up the Normandy cliffs, after the Commandos followed by the Rangers, made it to the beach.

The Commandos mission was still largely unknown to them. The whole operation was "top secret." It seemed like a suicide mission to the officers who knew the details of "Operation Overlord." Lt. Col James Earl Rudder, who had taken command of J.L.'s elite unit in May, is reported to have laughed when told of their mission. A United States Army intelligence officer in the room gave his opinion too. "It can't be done. Three old women with brooms could keep the Rangers from climbing that cliff."

Although initially stunned by the magnitude of the task, Rudder stepped up his Rangers training program focusing on cliff climbing and amphibious tactics as the date of the assault drew near.

In May 1944, the battalion participated in a full-scale pre-invasion exercise on the English coast with training help from the British Commandos.

Rudder's orders were to scale the Normandy cliffs and knock out the German defenses on top of Pointe du Hoc.

After Rudder took command, J. L. recalls, "He offered me a promotion to Sergeant, but I immediately turned it down. I knew what a Ranger Sergeant's job was, and I didn't want it!

"After I turned down the promotion, Rudder complained to Ike.3 Ike offered me the promotion again. I couldn't turn down our Allied Supreme Commander. I reluctantly accepted the promotion.

THE D-DAY INVASION

I Am Promoted to Staff Sergeant, even Though I Refused the Position

Just before 6AM on June 1st, the Rangers marched through the streets of Weymouth, England, to board the HMS Ben Machree to take them the 150 miles across the English Channel to the Normandy beaches.

The citizens were full of hope for victory over the Nazi empire and staged a spontaneous send-off for the Americans At that early hour, they turned out in mass to cheer on the American soldiers. The street was lined with people several rows deep. School children sang the National Anthem and waved American flags. The dock workers shouted out, "Give 'em hell, Yank!"

The Ben Machree was a former English Channel steamer ferry pressed into military service by the British Navy. The steamer was part of the huge invasion armada. On board the Ben Machree, the Rangers awaited orders from Ike for the invasion to begin.

On June 4th, one day before the planned invasion, Ike came to J.L. again. "He told me that the Commando who was our Staff Sergeant had become incapacitated. Ike wanted me to take that position. I refused again. But this time, he said that I had to take it whether I wanted to or not.

"Then minutes before the start of the invasion, the Tech Sergeant cracked up. He couldn't take it. I got promoted to that job. That meant that I would be the first out the door of the landing craft. I would be the first one in the water to be exposed to enemy fire and had to lead the thirty-five others in the landing craft into the water to blow up the mines and cut the razor wire under intense fire from the enemy.

"My friends were depending on me to lead the way. It was a responsibility that I didn't want, but I would do my best.

"June 3rd was just another day. We hadn't been doing much training on board the ship. I was eating supper when Ike came in. He knew every Commando by name. We all loved Ike. He didn't want us to call him General Eisenhower."Just call me Ike," he said.

"General Eisenhower told us that just ten soldiers out of the first one hundred fifty would make it out of the water alive trying to get to the beach.

"Ike really cared for all of us. He even listened to our suggestions. For example, Ike planned to drop us one mile off the beach, and we'd have to swim and wade the rest of the way. We told him that too many men would die if we were dropped that far off shore.

"Ike's concern was that the extremely heavy enemy fire close to the beach would put the landing crafts and the Commandos in them at greater risk. We assured him that we would protect the landing craft and persuaded him to made the drop only a half-mile off the beach.

"We explained to Ike that even with a life jacket on, if we were shot in the water, we could not hold our head up. We would surely drown if wounded. At least if we were wounded and made it to the beach, we could try and crawl to a safer place. "Ike listened and finally agreed with us. His decision saved many lives.

"When Ike came into the mess hall on the evening of June 4th, he ordered everyone out but the 150 hand picked, specially trained Commandos. I knew this was it. Ike announced that we would board the ship in the morning for the invasion. Men cheered and hollered. They wanted Ike to feel good. He said over and over,"Good boys, Good boys."

"I don't think the troops meant it though. None of us knew what war was like. None of us had been in combat before. We were all green. We had never shot at another human being nor had we been shot at.

"As I looked around the room, all were not shouting. Some were openly weeping and crying. Others sat in silence dropping their head into their hands too stunned and numb to speak or move. For me, I had a hard feeling in my gut like stone. "Ike told us that if we were successful, then we would be marked men by the Germans. They would never take me prisoner once they found out that I was a Commando. We would have to fight it out. I would have to kill or be killed because surrender for a Commando meant death by a German firing squad. I fought through Europe without anything identifying me as a Commando. The only identification I had was my dog tags.

The Providence of God

"Unbelievably, something strange happened as soon as Ike made the announcement to us that the invasion would commence in a matter of hours. The heavens began to roar with thunder and lightning flashed across the English night sky. The wind began to blow like a hurricane and roar like a locomotive. I had never witnessed a storm so fierce."

This storm was the worst in the English Channel in over two decades. The invasion originally scheduled for June 5 would either have to be postponed or canceled.

Instead of canceling the invasion or postponing it for a few days, General Eisenhower made the decision for a June 6th invasion at about 9:30 on the night of June 5th. The allied meteorologists correctly predicted an opening in the storm just long enough for the invasion to be successful. The German weathermen missed this lull in the raging storm.

Another factor for success that the storm helped create was German General Erwin Rommel's decision to leave the German defenses along the Atlantic coast and travel 650 miles from the French coast to Ulm, Germany, for his wife's birthday on June 6th.

Adolf Hitler had placed Rommel in charge of defending the coast from an anticipated allied invasion. He was one of the best strategists in the German high command. Rommel was convinced that the Allies would not invade in the storm. Thus, Rommel was not present to manage the German defenses and their formidable Atlantic Wall of Defense that he had been in charge of building and was in charge of defending.

The last thing that the German high command expected was a massive invasion on June 6th. The invasion was anticipated but came as a complete surprise to the enemy.

D-Day

Sgt. Doolittle continues. "We were still on board the transport ship through the storm. "At 3 o' clock on the morning of June 6th while we were eating a breakfast of flapjacks and coffee, we got word that the invasion was on.

"Ike and the Chaplain really got into it. Ike wouldn't allow our Chaplain to speak to us on the eve of June 5th, the original date for the invasion. Now, the Chaplain insisted on talking with us before we climbed down the ropes into the waiting landing craft to take us to the beach and face the guns of death that waited for us.

"The big guns of our battleships were already blasting away trying to prepare the way for us. Ike didn't want the Chaplain to talk to us. "You're gonna soften 'em up," he said. But the Chaplain won out. I'm glad that he did!

"The Chaplain told us the truth. "In fifteen minutes, many of you will be dead. Your officers are predicting that ninety-nine percent of you will die. There is not much hope for you. If you've never faced death, you're looking at it square in the face. But, you have a chance. If you ain't right, I want you to pray right now. All you need is two seconds. Ask the Lord to come into your heart and give you salvation and eternal life, and you'll be right." The chaplain then said a prayer for us.

While he was praying, orders came to load the landing craft. A lot of boys got right with their Maker in those moments. I will never forget that Chaplain and his honesty and his ministry to all of us.

"However, four men cracked up as the chaplain talked. One soldier put his hand over the top of his head screaming at the top of his voice. These men couldn't and wouldn't be going with us. "In order to go where we were about to go, you had to be right. I couldn't have gone if I had not been ready to face God. I had come to know Christ as my personal Savior as a teen-ager at a revival held at my church. And, I prayed the night before the invasion for God's mercy, grace, and protection.

On the bridge of the HMS Ben Machree, at 6 o'clock in the morning, Lt. Col. James E. Rudder shouted the orders to his men. "Now listen… Rangers! Show them what you are worth… Good luck guys! Demolish them… Departure in five minutes."

Sgt. Doolittle and his fellow Commandos departed about forty-five minutes ahead of the Rangers. The Rangers boarded their crafts around 6AM.

J. L. remembers, "As we boarded our landing craft, no one said a word. I boarded the Higgins Craft for the invasion with my "K" ration, my carbine, my raincoat, and my life jacket. I knew the Lord was with me in life or in death as the sun rose on June 6th. I could have never led the way or have had the courage to do what I did without being ready to meet the Lord."

The diesel engines moaned as they sped toward the heavily fortified German defenses to establish a beachhead where thousands and thousands of soldiers would soon follow the Commandos to begin the march and fight for every inch of land in order to liberate Europe and save the world from Hitler's barbaric cruelty and the Nazi Third Reich.

Back in the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt led the nation in prayer. 4 Americans every where prayed. Churches opened their doors on June 6th for prayer. Congregations and their pastors poured into them to ask the God of heaven to protect the soldiers and win the victory.

German Defenses

Hitler knew that a full scale invasion would be made by the allies from the English Channel, but he didn't know where along the French coast that the attack would occur. Hitler made the French coast into an impregnable fortress with a belt of strongpoints and gigantic fortifications up and down the Atlantic coast. He made thousands of slave laborers work day and night to build the defenses. Millions of tons of concrete were poured. So much concrete was used that all over Hitler's Europe it became impossible to get concrete for anything else. Staggering quantities of steel were used. By the end of 1943, over half a million men were working on Hitler's Atlantic wall. Moreover, he had placed Germany's greatest military mind, General Erwin Rommel, in charge of repelling the expected Allied invasion.

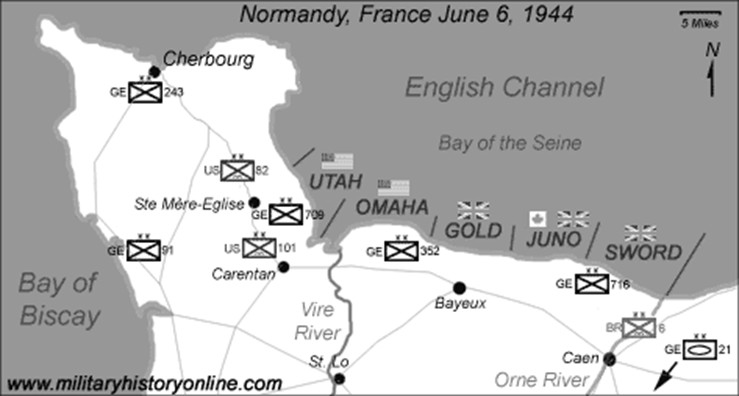

If the Commandos could survive through the beach landing, J.L. and the Rangers were to neutralize the German fortification on top of Pointe du Hoc by destroying the battery of six 155mm guns which dominated the beaches. They were also to seize a German observation post. Destruction of this battery was critical to the success of the invasion. Although planners had provided for naval and air bombardments of the Pointe, a direct infantry assault was the only certain way of neutralizing the fortification.

The Pointe du Hoc fortress was believed to be one of the strongest forts in Hitler's Atlantic Wall and possessed incredible firepower. It was defended by the German 352nd Infantry Division composed of both veteran and young soldiers. It was located on cliffs 117 feet high. These guns, along with the German Army divisions located nearby, dominated the Utah and Omaha Beaches and were totally able to prevent a successful Allied invasion of France. The success of the initial invasion depended on these guns being put out of action quickly. It is no wonder that the American officers thought that this was a "suicide mission."

J. L. would lead his men who had never been in battle against this terrifying defense. He would be the first out of the landing craft and lead his men on to the beach and up the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc.

The Water Turns Red with Blood

J. L. continues, "As we neared the drop-off point a half mile from shore, I was thinking that I had to keep going forward. I was by the door that would lower us into the water. I would be the first off. I knew if the lead man didn't go, no one else would. If I died, I knew I was ready. Intense heavy fire was all around us. I can't describe it to you. I had to steel my nerves to face it.

"But, one of my men wouldn't get off the craft. The Navy Lieutenant was shouting orders from the back."

The Sea Bee's who piloted the crafts had orders that any man who refused to get out would be thrown into the icy-feeling 58o water.

I shouted back to the Lieutenant, "Leave him alone! Send him back!

"I knew that he couldn't help us in the shape that he was in. He would have been a hindrance. The Lieutenant took him back to the ship. He was soon discharged. I received a letter from him after the war thanking me for what I had done for him.

"The gate opened and I plunged into the water. I cannot tell you how I felt. You ain't got no home when you come outta there. You ain't got no bed, no where to sleep until it's over with. You ain't even got a country. There's only one thing you can do. That's keep going forward. You sure can't go back.

"An important part of our mission was to deactivate the mines. When we began that dangerous task, I thanked God that the mines had rusted and were not effective. The salt water in the English Channel had done one dangerous job for us.

"Next, we had to blow up the razor-sharp barbed wire that we encountered twenty to thirty yards from the beach. We were well qualified for this operation from our training near Daytona Beach. We did it! And, then we continued toward the beach."

At Utah Beach, almost always, the first Commando out of each boat was killed. The men following their leader sometimes jumped over the sides of the crafts to avoid the frontal fire from the Germans. Hoping to swim ashore, some men drowned and even more were shot to death by the German guns positioned on top of Pointe du Hoc and German infantry defending the beach. The surviving Commandos either swam or waded ashore and entered the battle to establish the beach head.

J. L. said, "Before we could even get out of the water, Germans popped-up out of their beach fox holes. They came up charging, shooting, and killing us before our men had a chance to fight back. The water in the English Channel turned red from the blood of our brave men.

"The Commandos were in the water at 5:15AM ahead of the rest of the Rangers. In the murky dawn, I saw a German soldier pop-up, but I couldn't squeeze the trigger. I could have got him too because I was a good shot. I saw him as a man and not as the enemy. But in the next instant, my fellow soldier took a bullet from the German whom I could have shot. Suddenly, I realized what had to be done.

"I was the first American soldier to reach Utah Beach. I stood up and signaled to my men that I made it and for them to follow me. My life jacket was shot to pieces, and I had bullet holes all through my clothes, but none had hit me directly. I had lived to make it to the beach!

"I waved my rifle up and down over my head. I was proud too. I wanted the Nazis to know that the United States of America had arrived!

"Many of the Germans we found on the beach were young—only 18 or 19. They, like us, were stunned. Many sat stupefied in their fox holes and couldn't fight. They had never seen anything like the military force following behind us. They weren't in their right minds. And, they didn't want to be there any more than I did.

"We would capture them and then smash their rifles on a rock. They would sit there waiting to be taken away prisoner. It was like the end of the world for them and for us. We had never witnessed anything like it!"

"We hit the beach ahead of the main invasion force. As soon as we hit land, we notified the Air Force. They dropped paratroopers and gliders from the 101st Airborne about a mile or more in front of us to prevent reinforcements by the Germans which could have driven us back into the sea.

"Once on the beach, we'd jump up and run and shoot our way to the safety of the next fox hole that had previously been occupied by a German. After seven hours of hard fighting and many killed, we had cleared the beach by 12:30 that afternoon. The landing crafts were able to bring troops right up to the beach by then. Even Ike came ashore on one of them."

Sgt. Doolittle was part of a 250,000 man invasion with 5,000 ships. It was the largest amphibious invasion in history. One British historian said, If the invasion had failed, Hitler probably would have retained power. The world as we know it today would not exist."

I Make It to the Top of Pointe du Hoc

The next assignment for the Commandos and Rangers was to clear the guns on the cliffs overlooking the beachhead and wrecking death and destruction on Omaha and Utah Beaches. High on that cliff, the Germans had a clear field from which to rain down fire on both beaches where our soldiers were landing.

The Pointe du Hoc cliffs were over 117 feet high. Its perpendicular sides jutted out into the Channel. Looking at the adjacent picture, to the right was Utah Beach and to the left was Omaha Beach. The six 155mm cannons were protected by heavily reinforced concrete bunkers. On the outermost edge of the cliff, the Germans had an elaborate, well-protected outpost, where the spotters had a perfect view and could call back coordinates to the gunners manning the 155mm howitzers. Those guns had to be neutralized.

Although the top brass who planned the invasion had provided for naval and air bombardments of the Pointe, a direct infantry assault by the Rangers and led by the Commandos was the only way of neutralizing the fortification.

The German defenders had been shocked by the naval bombardment and the improbable assault on June 6th. Nevertheless, they quickly responded.

J. L. describes climbing the cliff. "We positioned ourselves at the base of the cliff. The Germans had anti-aircraft guns, tanks, and everything else you can imagine. The Germans were shooting at us from the top of the cliff and hurling down potato smashers, German grenades, at us."

The basic method of climbing the cliffs was by rope. Each rope climber carried three pairs of rocket guns which fired steel grapnels and pulled up plain three-quarter-inch ropes, toggle ropes, or rope ladders. Grapnels with attached ropes were an ancient tried and proven technique for scaling a wall or cliff, But in this case, the ropes had been soaked by the ocean spray and often were too heavy. Commandos and Rangers watched with sinking hearts as the grapnels arched in toward the cliff only to fall short because of the added weight from the water soaked ropes. Still, an adequate number of grapnels and ropes grabbed the earth at the top of the cliffs. The dangling ropes provided the way to scale the cliffs.

But, the Germans rushed to the cliff's edge and put down devastating ordnance against the Rangers. It was like shooting fish in a barrel. Moreover, they cut down as many ropes as they could to prevent the assault.

The Commandos and Rangers were pinned at the foot of the cliff with the sea behind them, an impossible cliff in front of them, and deadly German fire above them. They had no where to turn.

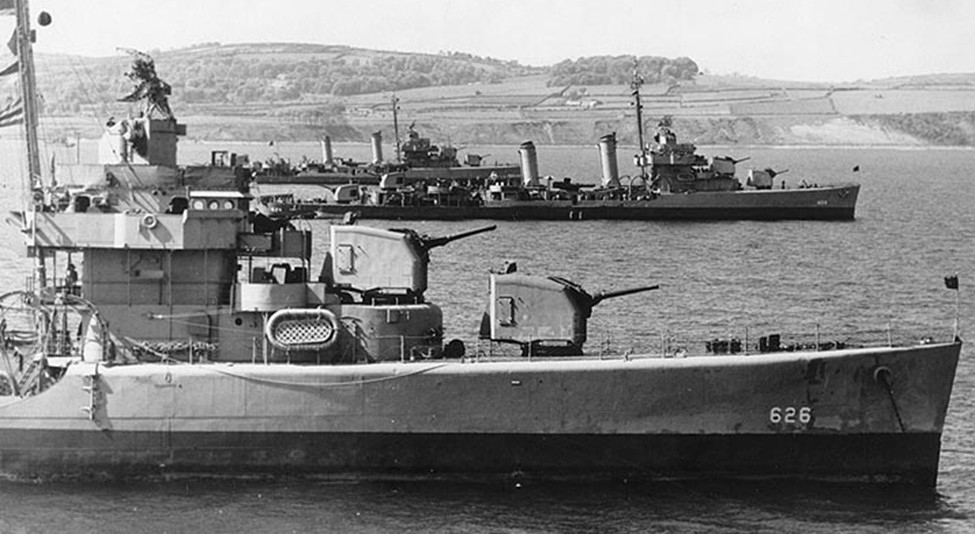

From the bridge of the U.S.S. Satterlee out in the English Channel, the ship's commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Joseph F. Witherow, Jr., saw the untenable situation of the Rangers who were sitting ducks for the Germans.

The Satterlee, a powerful Gleaves-class DD 626 Destroyer was a fearsome part of the giant naval armada supporting the invasion.

Without a second thought of putting the mighty destroyer and his 276 crewmen in jeopardy Witherow moved the powerful ship to within only 1,500 yards of the cliffs and opened fire with her 5 inch guns and heavy machine guns on Germans assembled near the

cliff's edge.

Many of the Germans scattered and the Rangers were finally able to begin their ascent to the top.

Assisted by withering, direct fire from the Satterlee, enough Rangers survived and took it to the Germans who had regrouped after the Satterlee had to stop firing for fear of killing Americans in friendly fire.

The Destroyer expended 1,165 rounds of 5-inch shells during the long day. In Witherow's official action report, he dryly noted, "Results were good."

J.L. continues, "I grabbed a rope and began to climb. I was one of the first to make it to the top." Others joined him and a precarious foothold on top of Pointe du Hoc was established.

The rigorous and demanding training that Lt. Col. Rudder had put the men through in England paid off. Rudder had been a high school football coach in Texas before the War and knew that hard practices on the field led to victory. The Rangers never broke in their assault against the German sea fortress.

J. L. recalls other complications he encountered. "The Germans had cut trees and used them to hide their 155mm cannons. They had hydraulics to lift them up, expose the guns, and then fire. We were helpless against them. "Moreover, once on top of the cliff, we had to take out the machine gun nests in the pillboxes. At the top of the pillbox was an air hole. We radioed for gasoline. But, we were pinned down and had to wait three hours for the gas."

After the gasoline finally arrived, J. L. said, "We had to pour gas down the holes and strike a match to it. There were six to eight men in each pill box. I hated to burn them, but that was the only way to get them out. Fortunately, some surrendered before I had to strike the match."

The Rangers had been decimated with casualties. Lacking men, supplies, and ammunition, the resolute remainder grimly held out against three enemy counterattacks. Of the 230 Rangers who had made the assault, only 70 remained by the late afternoon of June 6th.

J. L. remembers spending the night of June 6th on top of the cliff. "I had a knife in my hand and a pistol in my boots. I would crawl, take a fox hole, rest, and crawl again. There was no let up in the fighting that night. I was lucky if I got ten minutes of sleep. I continued to fight hard all day on June 7th on top of the cliffs.

"On that day, the second day of battle for me, I got shot. But, I felt the Lord's presence with me in a special way even in the midst of the carnage and suffering around me. I was still able to eat my ration that night. I had saved it for as long as I could since I was afraid that I wasn't gonna get another."

"K" rations provided 2,830 calories, which supplied the soldiers with enough energy for the entire day. The contents usually consisted of a peanut bar, bouillon powder, canned meat, a powdered beverage, chewing gum, and, cigarettes.

Promised reinforcements from Omaha Beach never arrived. The Omaha Beach operation had encountered serious setbacks and for a time, was in danger of failure.

Most of the Rangers on top of the Pointe5 had not slept for forty-eight hours. Food and ammunition were practically gone. The number of men able to fight continued to fall. They were massively outnumbered ten to one. Yet, the Rangers never lost control of their objective and never pulled back.

Today's Rangers are fortified with the motto, "Rangers Lead the Way," which was given to them by General Norman Cota based on their valiant gallantry in the heat of battle on D-Day.

I Rescue Strom Thurmond

"Around 9 o'clock on the morning of June 8th, we met up with the paratroopers who had landed in gliders about a mile or so in front of us. "To my great surprise, I found Lt. Col. Strom Thurmond from Edgefield in a wrecked glider. He was a member of the 101st Airborne Division and had been trapped in there all night."

Thurmond was one of 165 men in 32 gliders to reinforce other paratroopers who had arrived earlier. The gliders could carry a Jeep and supplies or 28 paratroopers. They were pulled by a C-47 and then released to glide down and then land without the roar of an engine which would have alerted the enemy.

The 101st Airborne Division's mission was to establish four exits for the Rangers in order for them to break out from their beach heads. This meant securing the marshland near the coast so that the Utah Beach Rangers could reconnoiter with the 3rd Army. These causeways needed to be secured because on each side of the exits, the area was flooded several feet deep in places. The floodgates had to be controlled by the Allies.

The 101st also had to destroy two bridges over the Douve River and to capture the La Barquette lock just north of Carentan. The lock controlled the water height of the flooded areas and it was essential that it be captured. If the floodgates were opened by the enemy, the flooded areas would present a strategic problem to accomplish the mission of capturing the port city of Cherbourg.

Thurmond's glider had crash landed in an apple orchard. His glider had been torn to pieces, and two paratroopers had died. Glider casualties caused by crash landings were extremely high during the invasion.

Strom was trapped inside. He and another soldier were trying to make an opening so they could get out. Strom called out, "I'm Lt. Col. Strom Thurmond."

J. L. remembers hearing his voice. "I sure was glad to hear that the paratrooper was somebody from back home. I was very glad that he was alive. After seeing the wreckage, It's a miracle anybody survived."

J. L. shouted back, "I know who your are! I'm J. L. Doolittle from Edgefield!" Thurmond recognized me.

"I told my men to cover me, and I ran to the wrecked glider and got him and the others out safely. We sure were happy and thankful to see each other! "It was amazing. Thousands of miles from home and two fellows from my small town of Edgefield who knew each other met in an apple orchard in France fighting the Germans!"

After freeing the future United States Senator, Thurmond ordered Sgt. Doolittle's platoon to stay until help came. J. L. replied, "I'm sorry Strom, I'm under orders from General Eisenhower, and he outranks you. Me and my boys have got to keep moving." "I did leave two of my soldiers with him and the other survivors. It took about an hour before help finally arrived for them."

Strom Thurmond said after the War, "If it hadn't been for Jimmy (J. L.) Doolittle getting me out of that wreckage, I would have likely been found and shot by the Germans."

Strom Thurmond was serving as the Eleventh Circuit Judge in Edgefield, South Carolina, when the United States entered the War. He resigned his judgeship In 1942 to enlist in the Army and fight for his country. Thurmond was elected to the United States Senate in 1954 and became the oldest person ever to serve as a Senator. He ran for President in 1948 as a Dixiecrat and won 31 electoral votes. He died in Edgefield in 2003 at the age of 100.

Earlier on the morning of June 8, unbeknownst to J. L. and his men, help from the 116th Infantry with their tanks finally reached the area around Pointe du Hoc near Vierville-sur-Mer. They had finally landed and had made it past Omaha Beach. They were just in time to save the Rangers who were now surrounded by German troops. The few Rangers who had survived the beach landing and the assault on Pointe du Hoc were being constantly attacked by German troops.

The 116th tank and infantry division burst through the German lines and rescued the 90 Ranger survivors included their wounded leader, Colonel James Rudder and Sgt. J. L. Doolittle.

THE BATTLE FOR CHERBOURG ON THE COTENTIN PENINSULA AND THE BREAK-OUT FROM NORMANDY

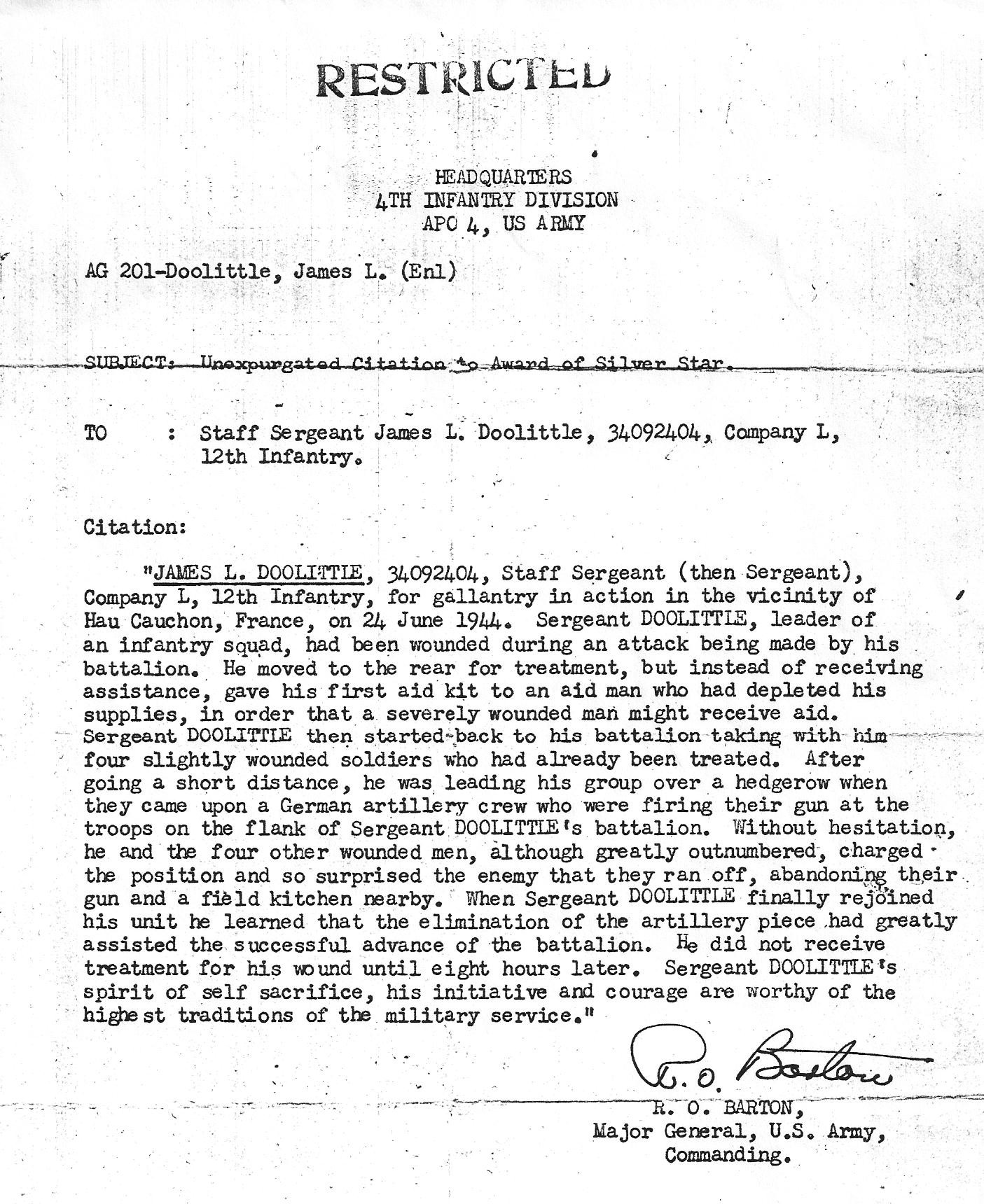

I'm Awarded the Silver Star

Eighteen days after D-day, on June 24th, Sgt. Doolittle as in another intense battle. The allies had secured the Normandy beach landing area and were on the move to clean out the Germans on the Cotentin Peninsula with the objective of taking the port of Cherbourg. The capture of Cherbourg was vitally necessary so that Allies could get supplies and men. If Cherbourg was taken, then supplies and men would no longer have to arrive on the beach which caused time-delaying logistics problems.

Near St. Mère Eglise on the Cotentin Peninsula was a small village called Hau Chauchon. J. L. was wounded in fighting near there. He moved to the rear for medical treatment for his wound. But instead of receiving assistance, he gave his first aid kit to another more severely wounded soldier who had depleted his first aid supplies. After giving up his first aid kit, he started back to the front with four other slightly wounded soldiers who had already been treated.

He was leading his small group. After going a short distance, they went over a hedgerow. To their surprise, they came upon a German artillery crew firing their gun and doing damage on the flank of Sgt. Doolittle's battalion.

Without hesitating and greatly outnumbered and wounded, Sgt. Doolittle led the charge against the artillery unit with the other four wounded soldiers following him. His actions surprised the enemy, and they fled in fear for their lives. They abandoned their gun and a field kitchen nearby. After J. L. and his men rejoined their battalion, he discovered that his heroic leadership in eliminating the German artillery unit greatly assisted in the advance of his battalion. Further, he didn't receive treatment for his wound until eight hours later.

Sgt. Doolittle's spirit of self-sacrifice, his initiative, and courage were recognized by the awarding of the Silver Star for his valiant action.

In a happy ceremony, if there is happiness in war, Sgt. Doolittle was reunited with the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who proudly pinned the Silver Star Medal on Sgt. J. L. Doolittle.6

The Silver Star is the third-highest combat military decoration that can be awarded to a member of any branch of the United States Armed Forces for valor in the face of the enemy.

I Make It to Paris

Sgt. Doolittle's 3rd Army went on to relieve the 82nd Airborne Division at St.-Mère-Église, and cleared the Cotentin peninsula of Germans. J. L.'s division also took part in the capture of the crucial port of Cherbourg on June 29th.

After taking part in the fighting near Periers, France from July 6-12, J. L.'s division broke through the left flank of the German Seventh Army. The Allies had broken the German lines around Avranches. But, the Germans tried to seal that breakthrough with their 5th Panzer Army on the night of August 6th after General George Patton's 3rd Armor Division was brought into the fray on August 1, 1944, when Patton's Third Army was officially operational as a combat army.

From August 9-12, J. L. was part of the 3rd Army's engagement and destruction of the famed 1st SS Panzer Tank Division.

So instead of sealing the breached line, the enemy was crushed by August 22nd, and the Normandy breakout was complete.

The march through France began.

Most of the French citizens in towns and villages that the Americans had liberated from Nazi power were ecstatic. They welcomed the Allies with crowds waving American and French flags. Some wept with gratitude. But, not all the French citizens were happy over their country's liberation.

J. L. continues his story. "In one French town (I don't remember the name). I was walking down the street with some other soldiers and heard a shotgun blast. The shell hit me, but my ammunition belt saved my life. Needless to say, that Frenchman never shot another American soldier. This guy was a Nazi sympathizer. After that, I was always on the watch for civilians especially those with guns."

On August 25th, the Allies liberated Paris. J. L. says, ""I was one of the first Americans into Paris."

After the liberation of Paris, the 3rd Army continued into Belgium and attacked the Siegfried Line.

By the middle of September, the division was fighting in the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest.

BATTLE OF HURTGEN FOREST AND THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE

I'm Awarded the Bronze Star

Helped by a drizzling, cold rain which screened their movement, J. L.'s Division moved into position in the shadow of the heavily wooded Schnee Eifel by nightfall on September 13th. They blasted a gaping, hole in the German line at Schnee Eifel and fought in a drizzling cold, miserable rain.

Next, J. L's division poured into Hürtgen Forest. They stopped the German attack in central Luxembourg and crossed the famed Siegfried line into Germany just east of the Belgian border.

The battle of Hürtgen Forest was one of the most fierce between United States and German forces. It also became the longest battle on German ground during World War II. And, it also was the longest single battle that the U.S. Army has ever fought. The battles took place from September 19, 1944, to February 10, 1945.

The temperature plummeted in the winter of 1944-45 in that part of Germany. Heavy snow fell and made for impossible conditions for the infantry. When they could catch some sleep, they camped out without even a tent for shelter.

In the battle of Hürtgen Forest, everything was tangled. A soldier could scarcely walk. Soldiers were wet and freezing. The mixture of cold rain, sleet, and at times, heavy snow fell.

For Sgt. Doolittle's tactical leadership in the Hürtgen Forest, he was awarded the Bronze Star.

His platoon had been decimated by death and injury from artillery and mortar fire. Skillfully placed mine fields, rotten winter weather conditions, and the German infantry and tanks added to their suffering and made casualties extraordinarily high.

Reinforcements had to be rushed forward to replace the depleted ranks. J. L. skillfully fused these fresh troops with more experienced soldiers to make a cohesive fighting force. Moreover, he assisted his new company commander in effecting a reorganization of the entire company. His good judgment, courage, and knowledge of the tactical situation set an example for the entire unit and aided in the combat efficiency of the company. Sgt. Doolittle's courage and devotion to duty reflected great credit upon himself and the military in general.

The Bronze Star Medal is awarded for bravery, acts of merit, or heroism in combat. It is the fourth-highest combat award of the United States Armed Forces.

General Eisenhower and (R) General Patton.jpg)

General George Patton pinned the Bronze Star on Sgt. Doolittle.7

J. L. said of General Patton, whom he served under, "I was given the Silver Star by Eisenhower and vividly remember the action that led to this honor. Patton gave me the Bronze Star, but I don't remember it as well. Patton didn't care about us like Ike did. He seemed to want glory for himself.

"At times, I was lucky. I sometimes rode in the Jeep behind Patton. The Germans wanted the "back man" because they thought he was the leader. The Germans drove their leader in the front vehicle. The Lord was with me."

The Battle of the Bulge

In December, J. L. was in the nation of Luxembourg facing the German Ardennes Offensive in the Battle of Hertgren Forest. This huge German offensive which took place in part of the Hürtgen Forest as well as in positions near the Forest came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

The Battle of the Bulge was Hitler's last gasp to avoid losing the war. Hitler's only hope was to break out of the suffocating and relentless victory after victory of the Allies.

In one day, the German Army burst through the Allied line advancing forty-five miles. For a while, the Germans almost broke through creating a bulge in the American line. Thus, the Battle of the Bulge.

It was the largest land battle involving American Forces in World War II. More than a million Allied troops fought in the battle across the Ardennes in the brutal winter weather from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945.

Adolph Hitler directed this ambitious counteroffensive with the object of regaining the initiative on his western front to compel the Allies to settle for a negotiated peace.

Another of Hitler's intentions was to recapture the Belgian port of Antwerp, and cut off and annihilate the British 21st Army Group and the United States' First and Ninth Armies north of the Ardennes. He also wanted to capture the Belgian port of Antwerp because Allied supplies entered Europe from that port.

The German attack came as a complete surprise to the Allies. In Hitler's own words, "The outcome of this battle will spell either life or death for the German nation and the Third Reich."

Poor communication in the Battle of the Bulge caused problems in command and control. Many radios were in the repair shops, and those at outposts had a very limited range over the abrupt and broken terrain.

J. L. recalls an incident when his platoon of 25 men got separated from the main force. "Me and my platoon got cut off from our Army by a German counter-attack. We were outnumbered 5,000 to 25, but we were not captured because we knew capture meant death. We took back an American hospital that the Germans had taken and saved the nurses and wounded men. The Germans thought that somehow our whole army had moved in, but it was just 25 of us and 5,000 of them."

Across the Rhine

SWIMMING ACROSS THE RHINE RIVER AND MARCHING INTO BERLIN

After the Battle of the Bulge, it was on to the invasion of Germany. The objective of capturing Berlin was now within sight.

J. L. said, "Due to my Commando training, I was in the group ordered by General Patton to swim across the Rhine River into Germany. He ordered us to take the German side of the River and secure it."

Patton told us, "Even if I have to order a two and a half ton truck to bring back all of your dog tags, we're going to cross this river!" We crossed the Rhine River into Germany after heavy fighting. I was one of the first Americans to make it into Germany."

After securing the German side of the Rhine, other soldiers of the 3rd Army including General Patton came across in boats. As a symbol of Patton's utter contempt for Hitler and his crumbling Nazi empire, Patton stood up in his boat and urinated in the Rhine River.

After the 3rd Army's heroic accomplishments, General Patton said on March 23, 1945. "From late January to late March, you have taken over 6,400 square miles of territory, seized over 3,000 cities, towns and villages including Trier, Koblenz, Bingen, Worms, Mainz, Kaiserslautern, and Ludwigshafen. You have captured over 140,000 soldiers, killed or wounded an additional 100,000 while eliminating the German 1st and 7th Armies. Using speed and audacity on the ground with support from peerless fighter-bombers in the air, you kept up a relentless round-the-clock attack on the enemy. Your assault over the Rhine at 2200 hours last night assures you of even greater glory to come."

J. L. continues with his story. "After crossing the Rhine, we moved quickly into the heart of Germany toward Berlin."

On May 2, 1945, the guns at last stopped firing amongst the ruins of Berlin. Hitler's self- proclaimed thousand-year Reich had ceased to exist. The German Führer himself had committed suicide on April 30th.

J. L. recalls his Berlin victory march. "In Berlin, I marched down the streets. We had defeated Hitler and his evil empire and driven the Nazi Third Reich off of the face of the earth. Out of my unit, my group of friends who had invaded the German stronghold at Normandy with me, only two others made it to Berlin with me. It was three Southern boys: Hardin from Alabama, Pierson from Tennessee, and me from South Carolina. I could not have made it without my faith in God and His providential protection over me."

Conclusion

J. L.'s Regiment fought in five European campaigns through France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany. The 12th Infantry was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for valor in action at Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge.

The Regiment was also awarded the Belgian Fourragère.

On July 12, 1945, after Germany's surrender on May 7th, the rest of the 12th Infantry, along with the 4th Infantry Division, returned to the United States from Czechoslovakia.

J. L. summarizes his service in World War II. "I fought all the way across Europe from the beaches of Normandy to Berlin. I served a record 199 days on the front line in the heat of battle without a break. I never lost sight of the enemy. I never took my boots off except to wipe my feet off and put my boots back on again. I've slept in cemeteries and slept under snow with only an army blanket and raincoat to protect me. I was wounded five times, and I was never out of battle more than a day.

"One wound saved my leg from amputation. It was thirty or forty degrees below zero in the Hürtgen Forest. My legs were frozen when I got shot in the leg by a tracer bullet. I didn't even feel it. One of my buddies noticed it. They had to thaw it out before giving me first aid.

"I was paid $21 a month for the first three months of service. After basic training, the Army raised us to $30, and I was receiving $186 a month when I was discharged.

J. L. said, "I'm not a hero. None of us were. We were simply doing our job as proud American soldiers."

In closing, let us all be reminded that the sacrifices made by Sgt. J. L. Doolittle and men like him give us the privilege of the freedoms that we have as citizens of the United States of America. They liberated suffering people and insured the continuation of our civilization. Let us salute them and all of our veterans. Let us thank God for Sgt. J. L. Doolittle and all of our veterans who have sacrificed on the field of battle to preserve our beloved nation.

And I'm proud to be an American

where at least I know I'm free

And I won't forget the men who died

who gave that right to me.

President Franklin Roosevelt's D-Day Prayer

June 6, 1944

My fellow Americans: Last night, when I spoke with you about the fall of Rome, I knew at that moment that troops of the United States and our allies were crossing the Channel in another and greater operation. It has come to pass with success thus far.

And so, in this poignant hour, I ask you to join with me in prayer: Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity. Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men's souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

For these men are lately drawn from the ways of peace. They fight not for the lust of conquest.

They fight to end conquest. They fight to liberate. They fight to let justice arise, and tolerance and good will among all Thy people. They yearn but for the end of battle, for their return to the haven of home.

Some will never return. Embrace these, Father, and receive them, Thy heroic servants, into Thy kingdom.

And for us at home -- fathers, mothers, children, wives, sisters, and brothers of brave men overseas -- whose thoughts and prayers are ever with them--help us, Almighty God, to rededicate ourselves in renewed faith in Thee in this hour of great sacrifice.

Many people have urged that I call the Nation into a single day of special prayer. But because the road is long and the desire is great, I ask that our people devote themselves in a continuance of prayer. As we rise to each new day, and again when each day is spent, let words of prayer be on our lips, invoking Thy help to our efforts.

Give us strength, too -- strength in our daily tasks, to redouble the contributions we make in the physical and the material support of our armed forces.

And let our hearts be stout, to wait out the long travail, to bear sorrows that may come, to impart our courage unto our sons wheresoever they may be.

And, O Lord, give us Faith. Give us Faith in Thee;

Faith in our sons; Faith in each other; Faith in our united crusade. Let not the keenness of our spirit ever be dulled. Let not the impacts of temporary events, of temporal matters of but fleeting moment let not these deter us in our unconquerable purpose.

With Thy blessing, we shall prevail over the unholy forces of our enemy. Help us to conquer the apostles of greed and racial arrogances. Lead us to the saving of our country, and with our sister Nations into a world unity that will spell a sure peace - a peace invulnerable to the schemings of unworthy men. And a peace that will let all of men live in freedom, reaping the just rewards of their honest toil.

Thy will be done, Almighty God.

Amen.

Postlude

On June 6, 1993, I was serving as pastor of Red Oak Grove Baptist Church, Modoc, South Carolina, in Edgefield County. During the service, I noticed one of my members was emotional and even at the point of tears. After the service, I asked him about it. He replied, "Don't you know what day this is?"

"Yes, this is D-Day."

"I was there," he told me.

On that day, I discovered that one of the men whom I greatly admired had been a part of the D-Day invasion. Little did I know the whole story.

J. L. Doolittle was the first man who I had ever known who was directly involved in D-Day. I decided that in 1994, which was the 50th anniversary of the D- Day invasion, that I would lead the church in a great celebration of this momentous event that changed the

course of World War II and changed history. Moreover, we would recognize all of our World War II veterans and all of our veterans who had served in the United States Armed Forces.

In preparation for this occasion, I spent considerable time interviewing and recording J. L.'s testimony about his remarkable World War II service. I invited his daughter, Jean Elwell, to sit in on the interview too.

Jean said, "I just didn't know what all Dad went through. This is the first time that I've ever heard him talk about it."

The interview was very painful for J. L. We'd talk awhile, and then we'd have to stop and cry. I've never experienced anything quite like that interview. I remember it like it was yesterday.

I transcribed the interview, organized the notes, and wrote his story which I read to the church. The church was packed and overflowing. After reading J. L.'s story, everyone stood and applauded and many were wiping tears. It was an awesome experience for all of us.

The Brass Quintet from our wonderful Ft. Gordon Signal Corps Band provided moving patriotic music. The service was one of those memorable days in the life of a pastor and his church.

After the service, I had World War II veterans who came up to me and said, "This is the first time that I've been publicly recognized for my service." It was the first public recognition for J. L. too.

After the service, we continued the celebration with a wonderful covered dish dinner in honor of all our veterans.

Since 1994, J. L.'s story has set dormant in my files but always alive in my heart. His niece did a report for school based on what I wrote for the 50th anniversary, and the Edgefield newspaper reported on it. I write a column of faith and inspiration for the Augusta Chronicle and did a short column on Sgt. Doolittle some time ago which was well received by the public.

But, I've always wanted to do more with his story. At last, I am able to do it. What prompted me is the class of World History students who I teach at Evans Christian Academy. I wanted them to read it as part of their assignment for our study of World War II. I wish all high school students in our country could and would read it too.

I took the 1994 story and wrote this book with a word processor. Because of my computer and the internet, I was able to do extensive research over several weeks. I was able to weave J.L.'s testimony into its historical context and add pictures illustrating what happened from D-Day to the crossing of the Rhine.

This book has been a work of joy. Every time I read J. L.'s story, I am inspired. His service and the service of men and women like him from the "Greatest Generation" must be told and retold again and again. I know his story will inspire all who read it. His story is of an humble man, doing his duty, accomplishing the extraordinary, and who has a heart for Christ.

May you be blessed by the story of Sgt. J.L. Doolittle and share it with others.

March 23, 2012

© Rev. Dan White 2012. All rights reserved. Revised March 15, 2012

Permission to publish on Back to Normandy June 22, 2012

{/tabs