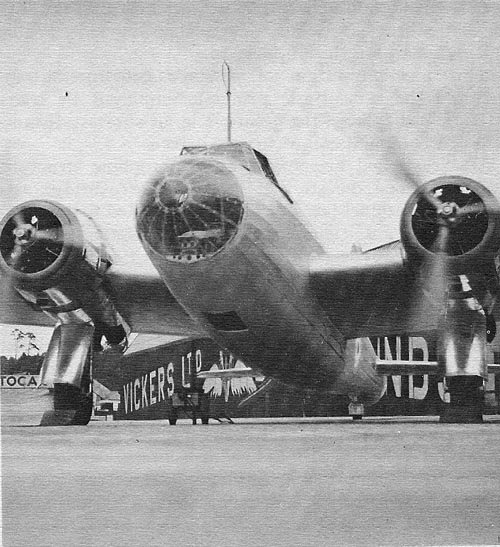

Just a few miles from the place where I live, the remains of an aircraft was discovered during dredging work. First few things that have been secured (a non-used parachute and some iron parts) gave the idea that it might be a missing aircraft of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a Wellington. There are no other missing aircraft reported within the borders of Dronten

The Wellington

technical info

Just a few miles from the place where I live, the remains of an aircraft was discovered during dredging work. First few things that have been secured (a non-used parachute and some iron parts) gave the idea that it might be a missing aircraft of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a Wellington. There are no other missing aircraft reported within the borders of Dronten.

According to the loss registry of the Ministry of defense of 1943 with the Vickers Wellington registration HD-Q and serial number HF544, showed that this airplane was shot down on 26 June at 1.11 hours. That happened by Helmut Lent of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1. The registry mentioned the location in the IJsselmeer near Urk, but this turns out to be so further South.

The Wellington of the 466 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force conducted a mission to Gelsenkirchen. The crew consisted of pilot a. G. Green, Airy, Bombardier navigator w. Riley, radio operator T. Atkinson and gunner g. Johnson. Only the body of navigator Riley is recovered and he is buried in Amsterdam.

Read the whole story on Back to Normandy

Reason for me to tell more about the Wellington.

My wonderful source: Alec Lumsden

Type

Twin engined medium bomber.

Wings

Mid-wing, cantilever monoplane; aspect ratio 8.83 light alloy Vickers-Wallis construction on geodetic principles.

Wing built in inner and outer sections connected through engine nacelles. Inner wing attached to fuselage by reinforced inner ribs, the single Warren truss main spar (pin-jointed at centre line) passing through, but not attached to, fuselage. Auxiliary spars fore and aft attached to inner ribs and fuselage main frames. The rear spar carries split flaps and Frise ailerons. Wing pane-ls fabric covered before assembly.

Fuselage

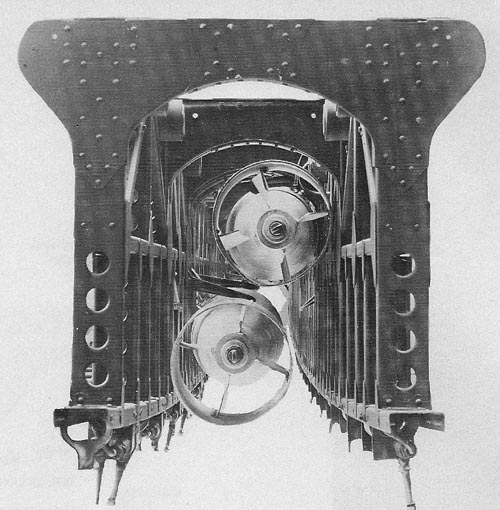

Four tubular longerons act as pickup points for nodal points of intersecting geodetic members. Fuselage fabric covered, oval sectioned and jig-assembled on two fabricated main frames at Wing attachment points. Other principal frames at tail attachment and cockpit wall. Bomb-bay divided longitudinally into three cells. Later Type 423 accommodated 4,000lb bomb.

Tail unit

Cantilever monoplane, geodetic construction, fabric covered. Trim tabs and horn balance on elevators (linked to flaps) and rudder. Rudder mass-balanced.

Undercarriage

Hydraulic retraction of all units. Vickers oleo-pneumatic shock-absorbers. Mkl version had main wheels enclosed by doors-later Marks had larger wheels leaving tyre partially exposed. Vickers pneumatic wheel-brakes.

Powerplant

Two Bristol Pegasus, Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp, or Bristol Hercules radial air-cooled or Rolls-Royce Merlin liquid-cooled engines. Three-bladed de Havilland, Rotol, Curtiss or Hamilton Standard propellers on air-cooled engines (except test installations) and three- or four-bladed Rotol on Merlin engines.

Standard fuel 634 imp gall in removable self-sealing wing tanks and 116 in nacelles-total 750 gall. In later Marks, long range tanks could be fitted in bomb-bay bringing total up to 1,305 gall giving nearly 17 hours endurance on ferry flights (about 2,000 miles).

Accommodation

Up to six crew, according to requirements. Could be flown solo.

Armament

Mkl-three hydraulically operated Vickers turrets-nose, tail and ventral. Single Browning gun in nose, twin in tail, 52 and single in retractable under turret. Nash and Thompson turret controls. Frazer-Nash ventral turret substituted for Vickers. Later had FN turrets, 2-gun front and 2- or 4-gun rear. Ventral deleted in favour of Vickers ‘K’ gas operated or Browning belt-fed .303in window-mounted beam guns. rWarload-bombs (up to 18 250lb in 3 cells or one 4,000lb ‘Cookie’ in Type 423 bomb cell) or mines or two l8in torpedoes and/ or long range tank(s) as required.

introduction

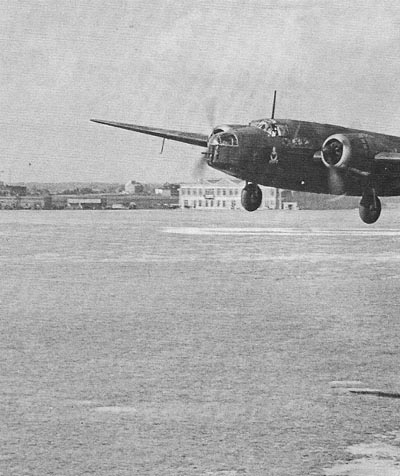

Many aeroplanes have captured people’s imagination over the seventy years or so since the first powered flight by the Wrights. The Vickers-Armstrongs Wellington bomber is certainly one of them but today, some thirty years after its heyday in front line squadron service with home-based Royal Air Force Bomber Command, it is perhaps remembered more as a famous name rather than for any particularly spectacular exploit. Why this should be so is not easy to determine, for the Wellington had its fair share of excitement and glory in its day. Perhaps its very capability of tackling almost any job to which a large and capacious twin-engined aeroplane could be put was responsible to a large extent.

The Wellington, which started its Service life as a medium bomber in 1938, was the mainstay of Bomber Command (and sole equipment of the East Anglian No 3 Group) until late in 1940. By this time, the first ripples were to be seen, heralding the fast rising tide of big, four-engined bombers. The Stirling was the first and, weighing around twice as much as the Wellington, with a correspondingly greater bomb-carrying capability, these much larger aircraft--followed by the Halifax and Lancaster--started flowing in numbers to the squadrons from late 1940 onwards. At the same time, with the steadily increasing Allied bombing effort, more and more squadrons were being formed, particularly as the Empire Air Training Scheme got under way, providing the badly-needed crews.

Nevertheless, there was much for the Wellington to do, particularly after the invasion of the Low Countries in May, 1940. In fact, so much demand was there for the Wellington’s services, and so adaptable had it become, that it began to appear in many other roles and in every other theatre of war, thereby proving its adaptability for tackling almost any work demanded of it. This included the dropping of 4,000lb bombs (‘Cookies’ or ‘Blockbusters’); minelaying; minesweeping; submarine hunting; torpedo dropping; some of the earliest electronic countermeasures experiments; high altitude flying with a pressurised cabin; glider towing; troop and ambulance transport trials; and, inevitably crew training of all kinds.

The Wellington was one of the greatest trainers of heavy bomber crews and continued in this work until its withdrawal from service in March, 1953-the last retiring from No 1 Air Navigation School at the end of that month.

Even then the geodetic construction-for which the Wellington had become so famous-continued to serve in its commercial successor, the Viking, in its initial form.

The very adaptability which made the Wellington so popular with the RAF accounted in no small measure for its being produced in greater numbers than any other multi-engined aeroplane built in Britain--11,461 all told.

This massive figure needs to be considered in relation to the effort involved in the geodetic construction, for it' was not at first sight the easiest or simplest to put together.

Photo: Wellington of the 149 Sqdn over Paris on July 14 1939. The squadron code letters were changed to OJ afterwards

This is a story in itself the geodetic design devised by Barnes Wallis being possibly the feature people most associate with the Wellington, apart from its somewhat endearing sobriquet, the ‘Wimpy’.

By common consent, the Vickers Wellington is among the top dozen most successful aircraft ever built and clearly justified the distinction of carrying the name of one of Britain’s greatest soldiers. l The great re-armament programme of the 1930s with its ‘shadow factories’ and accelerated by the Munich crisis of September, 1938, spurred on the Wellington production run which lasted until after the War’s end and resulted in its having a longer and more distinguished operational career than any other British bomber. When the Wellington went to war, it acquired an almost legendary reputation for withstanding battle damage, a capability which was largely due to the unique basket-weave geodetic construction-which itself has aptly and variously been described as a ‘collection of holes linked together in the shape of an aeroplane’, a ‘knitted’ or a ‘cloth bomber’.

Not only did the Wellington form the striking force of No 3 Group; it became the backbone of Bomber Command in the critical early years of the War and went on to serve in all major theatres of the campaign with all RAF Commands (including Fighter), and eight Commonwealth and Allied air forces--still being front line equipment when the war ended in 1945.

Blooded in combat on the second day of the war (September 4, 1939), the Wellington carried the greater part of` the bombing offensive on German naval and industrial targets for the next twelve months. Although it led the way in proving the value of the power-operated gun-turret, its first daylight operations were disastrous.

These proved that even with this powerful defensive weapon, large bombers could not carry on the bombing offensive in daylight against heavily defended targets unless they had very strong fighter escorts. Unhappily for the Wellington in its early operations, the only high speed fighters in large-scale service were intended for short-range interception duties and quite unsuitable for such escorting. All British bombers had turrets mounting rifle-calibre .303in machine guns whose maximum effective range was about 600 yards. The opposing German fighters at the beginning of the war mounted 20mm cannon as well as lighter weapons and could attack in comparative safety from greater distances. At night however, the British guns in their multiple mountings came into their own since fighting distances tended to be closer, particularly in the early part of the war prior to the wide-scale use of airborne radar by the Germans. The problem of daylight defence the United States Air Force was eventually able to overcome with its long range fighters and heavy .Sin machine guns, when the next and more powerful stage was reached in the daylight war in the air. It was the Wellington and its gallant crews in the early stages of the war, however, which had revealed the true gravity of the problem.

Used to demonstrate the practicability of pressure cabins and the earliest jet engines and turbo-props at the end of its career, the Wellington provided the essential basic information on these two aspects of future airliner construction and operations which Vickers chose to pursue in strength when the war was over.

end of the biplane

For several years before the expansion really got under way, the RAF bomber squadrons relied on interim aircraft, mostly biplanes and of somewhat doubtful value in the light of the large number of German monoplane fighters already known to be in production. The Fairey Hendon and Handley Page Harrow were the first of the (then) heavy bomber monoplanes. The Vickers Wellesley and Bristol Blenheim with their retractable undercarriages, flaps, and variable-pitch propellers, heralded the rapid elimination of the biplane as a medium and light bomber from 1936 onwards.

Since its creation in 1918, the Royal Air Force has never been without at least one Vickers aeroplane in first line service, and, indeed today, 56 years later, the largest and fastest passenger/ freight transport in Strike Command is the Vickers-designed VC10. With the requirement in 1931 for a general purpose and torpedo bomber type to replace the Fairey III/ Gordon/ Seal, Blackburn Ripon/Baffin/Shark and Vickers Vildebeest/ Vincent series, a specification (G.4/ 31) was issued by the Air Ministry for tender and most of the major manufacturers competed.

The competition was won by Vickers which proposed two designs, a monoplane and a biplane. The biplane was evolved from the well proven Vildebeest design, via an unsuccessful prototype to the earlier (M.1/ 30) specification but introduced for the first time a novel, geodetic, form of construction in its fuselage devised by B.N. Wallis who had not long been working at Weybridge with R. K. Pierson, the Vickers chief designer. The monoplane’s construction followed similar principles and was entirely geodetic.(The principles and construction of geodetic airframes are described in the next chapter.)

Against the wishes of Vickers, the biplane prototype was ordered but, at a board meeting on August 12, 1932, the company decided to build the monoplane as well, at its own expense. The eventual cost was £3O,271. When both had been built, the monoplane, later to become the Wellesley, was far the superior in performance, a fact which caused Sir Robert McLean, Chairman of Vickers (Aviation) Limited, to write an impassioned letter to Air Vice-Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding (later Lord Dowding) in July 1935. He stressed to Dowding the desirability of building the monoplane rather than its biplane stable companion of which the Air Ministry had placed an order for 150 earlier that year. ‘ln my view,’ wrote Sir Robert, ‘it is not a modern machine.’ He added that, until Dowding could decide whether the Company were to be allowed to build the monoplane, the Vickers Board did not wish to proceed with the biplane design. History records the result-orders for the Wellesley totalled 176 and the G.4/31 biplane was abandoned.

Seven months after deciding to proceed with the two contenders for the G.4/ 31, the Vickers board put forward a tender for the construction of a prototype all-metal twin-engined bomber in accordance with another Air Ministry specification-B.9/ 32. This required a range of 720 miles with a bomb load of 1,000lb-a modest enough demand. The design was of a high wing monoplane with a fixed undercarriage and either two 660hp Bristol Mercury VI or Rolls-Royce Goshawk I steam-cooled engines. A broadly similar design, the Handley Page Harrow, was put into production and so, later, was the Hampden from the same company initially also to the B.9/32 specification. In the light of further tests with geodetic construction, however, Vickers scrapped the original proposal under B.9/32 in October 1933 and made a start on a completely new design. This was to be entirely of geodetic construction and to have a mid-wing layout, two Goshawk engines (later changed to Bristol Pegasus), retractable landing gear and was in every respect technically advanced, benefiting from the Company’s experience with the Wellesley.

Such were the merits of the light, basket-type of structure, combining high strength with light weight and permitting excellent aerodynamics,the new B.9/32 design from Weybridge would have a range of 2,800 miles with a bomb carrying capacity of 4,500lb-four times the requirement and slightly more than visualised by T renchard ten years earlier. This new bomber was eventually to become the Wellington.

first bomber raid

The first production Wellington was delivered to No 9 Squadron at Mildenhall (Suffolk) in October, 1938 and, by the outbreak of war, six squadrons of Bomber Command were fully equipped and operational with Mkls. Four others were working up.

At 18 15hrs, on September 3, 1939, nine Wellingtons from Mildenhall (with 18 Hampdens from Scampton) took off on what should have been the first bombing raid of the war. They were briefed to attack German warships off the Danish coast but failed to locate them. Next day, fourteen Wellingtons (this time with 15 Blenheims) took part in the historic attack on ships of the German Navy at Brtinsbuttel, and were badly mauled by German fighters.

The following year, numerous sorties were flown as armed reconnaissanccs during the Norwegian Campaign and, after the German break-through in the Low Countries, Wellingtons attacked targets in support of the land forces.

By this time, however, and as a direct result of the experiences in 1939, daylight operations within reach of enemy fighters were severely curtailed and finally had to be abandoned because of the Wellington’s poor defensive armament. Later in the summer of 1940, Wellingtons on night operations bombed the German barges concentrated for the invasion of Britain.

first blockbuster

As the early months of the war passed, Wellington production increased steadily. The aircraft itself underwent the normal process of development and improvement, such as the installation of the more powerful Merlin and Hercules engines and better armament. Wellingtons were now almost entirely employed on night bombing and, on April 1, 1941, a Wellington Mkll delivered the first 4,000lb ‘Blockbuster’ to Hitler’s Reich, on the port of Emden.

By May, 1941, there were twenty-one Wellington squadrons in Bomber Command, and a year later, of the 1,043 aircraft which took off to make the historic first of the three ‘thousand bomber’ mass attacks on Germany (Cologne) on the night of May 30/ 31, 1942, no fewer than 599 were Wellingtons. By this time, however, the four-engined ‘heavies’ were coming forward in increasing numbers and the Wellingtons were gradually phased out of Bomber Command, making their last bombing attack from England on October 8, 1943. They were still widely used by Coastal Command-Wellingtons were the first aircraft to use the Leigh-light for illuminating submarines and surface vessels by night after they had been picked up by radar. They were also used very widely for every imaginable training duty, both at home and in the Middle East.

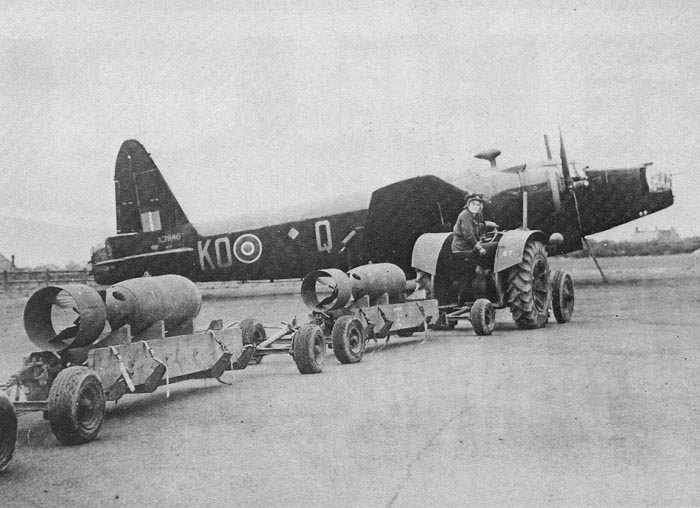

Photo: The type 423 modifiction enabled the Wellington to carry 4.000 lb bomb (Blockbuster or Cookie) seen here being wheeled up to a Wellington III

Photo: a trolley load of 250 lb bombs about to be hand-winched into the bomb bay

from weakness to strength

Photo: Before a raid Mk IC OJ-N of the 149th Squadron (one of the least five to bear this letter at some time) squats between trees at its dispersal point at Mildenhall, Suffolk in 1940. A refuelling bowser drawn by a tractor stands by its starboard wing, bomb trolleys with 250 lb bombs beneath the open doors

When the war began, there was no clear plan for the use of Bomber Command’s rapidly expanding front line strength. Admittedly some aircraft were of a stop-gap nature. Some like the Fairey Battle which was deficient to a disastrous extent in defensive armament. Of Blenheims, however, there were substantial numbers. Both of these types were classed as day-bombers. The heaviest bombers in the Service were the Vickers Wellington and Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. These two aircraft, together with the Handley Page Hampden, were the mainstay of the Command. Initially, since the enemy did not at once attack the UK in strength, only limited attacks on the German Navy at sea and the dropping of propaganda leaflets over Germany were planned.

So began the ‘Phoney War’-phoney, that is, to all but those who took part in it. The early raids were mostly by day against German Naval ships-navigation by night was not then a very exact science in the squadrons. The casualty rate among crew was shocking-particularly for the Wellingtons and one grave lesson, as we have seen, was quickly made clear: unescorted bombers by day were very easy prey to fighters operating close to base, particularly as the Germansalready possessed an early form of radar warning. The RAF had no suitable long-range escorts.

The bombers’ defences were inadequate and, despite unbelievable gallantry in pressing home attacks on small and difficult targets, they took a severe hammering. The retractable under-turrets of the Wellingtons were almost useless, slowing the aircraft by as much as 15 knots just when they needed all the speed they could get. The turrets could not be used against high beam attacks and, in any case, the weight of defensive fire was minimal. The German fighters very soon worked this out and, almost at once, Wellington losses made two things imperative-to cease daylight armed-reconnaissance flights without fighter support and to provide better defensive firepower.

This hastened the already planned introduction of Frazer-Nash turrets and led to the installation of window-mounted beam guns. The Wellington also had other serious weaknesses. It had no armour protection nor had it self-sealing fuel tanks. It caught fire easily and the fabric covering on the wings was soon destroyed. Those aircraft which did get home all too often did so with tanks drained through bullet holes or still gushing petrol.

Lessons are quickly learned in war however. and modifications for installing armour plate and self-sealing fuel tanks were in hand within weeks of these early raids.

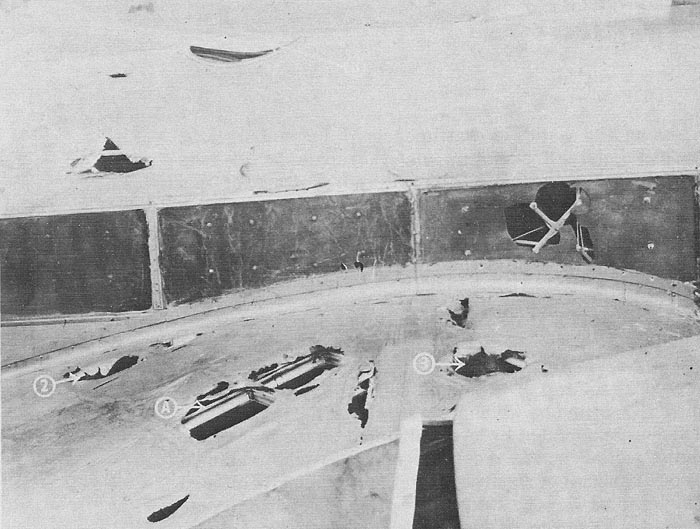

Despite these weaknesses, the Wellington was quite remarkably battleworthy and would still fly despite the removal of half its basket-like structure. Yards of its fabric could be torn or burnt off and on numerous occasions the Wellington still found its way home. lts susceptibility to fire remained its major weakness. (One man crawled out onto a wing to put out a fire-and won the VC.) Its interior could be bitterly cold and was draughty at the best of times. ,Though its range was good, its speed (about 250mph) was unspectacular. Defensive armament was adequate at night and, had it had the mid-upper turret originally proposed for the B.9/ 32, it might have fared by day better than it did. Nevertheless, as a night bomber, despite its modest bomb-carrying capacity, it was very successful and highly regarded by its crews. Bombing was not its only operational role with Bomber Command and minelaying in enemy waters (Gardening) was a routine chore supplementing nightly attacks on communication centres, marshalling yards and other industrial targets.

Wellingtons were used at one time or another by at least 76 squadrons of the RAF and Allied air forces. They operated with Bomber, Coastal, Transport, Flying Training and Fighter Commands-the last for a brief time in one Flight of No 93 Squadron in 1941. Four Polish squadrons (Nos 300, 301, 304 and 305) and one Czech (No 311) operated the Wellington until it was replaced by Halifaxes and Lancasters. No less than 13 Canadian Wellington squadrons were formed, mostly in No 6 Group, Bomber Command. The first Commonwealth squadron, No 75 (NZ) was largely composed of New Zealanders, one of whom was Sgt James Ward, VC, the only winner of the award on a Wellington. Three Australian squadrons flew Wimpies (Nos 458, 460 and 466), and one South African (No 26) and one Free French (No 326) were Coastal anti-submarine units. Four RAF Wellington squadrons were named; No 99-Madras Presidency; No 149-East India; No 214-Federated Malay States; and No 218-Gold Coast.

In Bomber Command, Wellingtons served with Nos 1, 3, 4, 6 and 8 (Pathfinder) Groups and one squadron (No 69) with the 2nd Tactical Air Force (previously No 2 Group), used the aircraft on reconnaissance for a short time. No 8 (PFF) Group. a corps d’elite. operated Wellingtons in 156 and 109 Squadrons.

Coastal Command Wellington squadrons were, to a considerable extent, transferred from Bomber Command, although some were specially formed for general reconnaissance (GR) duties. Twenty-two Wellington squadrons in Britain, Iceland and the Middle East operated Ml<sVIII, XI, XII, XIII and XIV Wellingtons at some time during the war, armed with torpedoes and depth-charges-~reverting to or from bomber duties as the exigencies of war demanded.

Transport Command gained in strength and importance as the war progressed, requiring the conversion of bomber Wellingtons from quite early in the proceedings. These ranged from the CMkIs (later designated MkXVs) to the more rugged glider-towing MkXs. There were seven transport squadrons using Wellingtons at one time, although towards the end of the war every available bomber type was used as a transport for supply, rescue and troop repatriation purposes. In addition, they were operated by BOAC and, briefly, by No 29 Squadron, SAAF for transport duties.

No discussion of Wellington activities can omit the Operational Training Units (OTUs), mostly under Bomber Command. No complete list of units which used the Wellington has ever been published and it is doubtful if an authentic list is possible to compile, so ubiquitous was this versatile aeroplane. It was used for all sorts of jobs, from the specialist to the pilot training and humble target-towing for fighter OTUs. No doubt readers can add to the author’s own list of Wellington units-which totals no less than 207. These are far too numerous to itemise but can be grouped under the following headings:

- Air Armament School

- Advanced Flying Schools

- Beam Approach Training Flights

- Central Gunnery School

- Central Navigation School

- Empire Central Flying School

- Experimental and development units of various kinds

- Ferry Training Units

- Operational Training Units

- Overseas Air Despatch and Preparation Units

- Refresher Flying Units

- Group Training Units

- Target Towing Flights

- Station and Communications Flights

- Air Gunnery Schools

- Air Navigation Schools

- Armament Training and Gunnery Units

- Conversion and other Training Units

losses and sorties

Bomber Command alone suffered some 47,000 men killed in action and nearly 5,000 wounded-about 12 per cent of the UK’s total Service and civilian casualties in World War H. These casualties were the result of 389,809 sorties on which 955,044 tons of bombs were dropped. The total losses of all types of aircraft was over 10,000. Wellingtons made 47,409 sorties with the Command (including 6,022 by OTUS) and dropped nearly 42,000 tons of bombs. In all, Bomber Command lost 1,332 Wellingtons on operations and a further 337 wrecked in accidents. On operations from the United Kingdom, Wellingtons flew 63,976 sorties totalling 346,440 hours flying. In the Middle East and Far East theatres of operations, flying hours totalled 524,769. Nearly 100,000 tons of bombs, etc., were dropped by Wellingtons. After the war, Wellington trainers tlew a total of 355,660 hours. At an average speed of 150mph, the grand total of 1,226,869 flying hours represents over 184 million miles. In addition to this, wartime training probably exceeded another million hours.

nightfighter attack

There were wide differences of philosophy between British and German bomber designers, at least in the early part of the re-armament race in the 1930s. British bombers were mostly equipped with gun turrets. Some of them were manually operated at first but later all were powered hydraulically, and these were mounted,in bow and stern positions with upper and lower gun positions as well. The German practice tended to favour grouping crews close together in the forward part of the fuselage, somewhat cramped and with manually operated gun mountings. The ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ layout may have been German good for morale but it had its limitations by comparison with the completely unobstructed fields of fire provided for British front and rear gunners, despite the isolation the latter involved.

The British policy paid off when cannon-equipped night fighters began to take their toll ofthe raiders attacking the industrial areas of Germany by night. The RAF were quick to learn how to combat these heavily-armed Luftwaffe night fighting Messerschmitt 110s and ]u88s.

The method was simple but uncomfortable, at least for the rear gunners. The method devised was the ‘corkscrew’-a climbing, rolling, diving, rolling and climbing manoeuvre.

This was very difficult for the fighter to follow and usually forced all but the most tenacious to break off the engagement, wait until the bomber steadied on its course again and then re-engage using its radar. All of this took time and distance and, of course, the limited fuel the fighter carried.

On many occasions the Corkscrew was successful and it called for the closest teamwork on the part of the bomber’s crew. The pilot, because of his position and his need to rely on his instruments, could not watch his attacker who almost invariably approached at night from dead astern.

From this position the night fighter crew could pick up and follow the bomber’s engine exhaust flames. The bomber pilot was therefore very dependent upon his crew, particularly the rear gunner and whoever was manning the midships astrodome, for precise warning of the position and height of any attacker they spotted in the darkness. The bomber’s gunners were at a disadvantage in that the fighter’s own exhaust flames were not easy to see from ahead. Once the fighter had been sighted and as far as possible identified, it was up to the gunner to tell his pilot what to do to make his evasive manoeuvres effective. At the same time the bomber’s pilot had to hope that his instruments would see him out of trouble and that the artificial horizon would not topple. Fighters also worked very closely with searchlights which themselves operated in powerful groups. A bomber which was ‘coned’ by a group oflights wasivery hard put to it to shake off the lights and hence could be an easy victim of night fighters. The overwhelming brilliance of these lilac-hued lights, even to crews wearing dark glasses, made the reading of instruments a very difficult occupation indeed. The bomber pilot therefore had to be both skilled in instrument flying and endowed with a highly disciplined crew if he was to find his target and survive. The discipline required for this sort of exercise is well illustrated by the following contemporary story:

The discipline

‘I had the good fortune to be the rear gunner on an ideal Wellington bomber crew. Every man of the crew pulled his weight on the ground and, what was more important, in the air .... For each eventuality, each man knew exactly what was expected of him. Our normal procedure was for the 2nd pilot or the captain, when not at the controls, to be stationed at the astrohatch to give additional aid to the gunners in their plan of search for night fighters. This method had enabled us on several occasions to spot enemy fighters when some distance away; and by taking avoiding action immediately, we were always successful in losing them.

‘On the night in question, there was a three-quarter moon and excellent visibility. We were returning from a sortie and did not expect any fighter opposition. We did not, however, relax our vigilance.

‘About a quarter of an hour after leaving the target, following a successful attack, I spotted two dull red lights (or so they appeared) close together following us on the starboard quarter. These two lights were in the dark part ofthe sky, the moon being on the port quarter. There were no clouds nearby and no cloud to silhouette an aircraft against. Indeed, I was not at all sure at first that the lights were an aircraft; I warned the captain and immediately avoiding action was taken but the two red lights still followed us.

We then turned to starboard in a tight turn and went down in a dive. During this manoeuvre, I saw the silhouette of an Me ll0 (*War-tiine RAF terminology. later corrected to `Bf`l l0`.) against the bright part of the sky and what I thought to be two red lights proved to be the exhaust glow from his twin engines. We found that we could not shake the fighter off, so we turned back on course and our evasive action took the form of undulating.

This fighter didn’t appear to be a keen type and followed us, still on the starboard quarter, about our own height (11,000 feet) and at about 1,000 yards range. After five minutes had elapsed, the fighter closed in to about 800 yards, opening fire with two cannons. The range was, of course. too extreme for .303 Brownings so I held my fire hoping that the enemy aircraft would close and give me a chance to have a crack at him. But he was a very shy bird and when we throttled back hoping he would overtake us, he fell back too, and kept the range at about 800 yards.

Every now and then, he would turn in and fire a short burst from .his two cannons and then continue as before.

‘This went on for about a quarter of an hour and having showers of explosive cannon bursting around the rear turret was far from comfortable. I was fully convinced that the only way to get rid of the fighter was to fox him into coming close to point blank range and shoot him down. I pause to remark that never for a moment did I doubt that I would get him first-why, I’m afraid I can’t explain ... that improved my morale 100 per cent. I asked the captain ... when the fighter opened fire again, to dive down as though we were out of control and when I gave the word, to throttle back, lower the undercarriage and pull the nose up-everything to slow us down suddenly. The resulting dive was rather hair-raising and, of the whole encounter, was the only thing that really gave me the ‘wind up’. The ASI registered 360mph in that effort which isn’t bad for an old Wimpy. Jerry was completely foxed into thinking that he had got us and he came down after us, closing in to give what he thought would be the coup de grâce.

‘What was most surprising to me, he came in from dead astern and when we throttled back, lowering the undercarriage, etc., we dropped from 360mph to l00mph in less time than it takes to tell. Jerry was taken completely by surprise and overshot. Instead of breaking away, he attempted to get his sights on us and when he found he couldn’t get his sights to bear, he pulled up into a climb dead astern. The range during this was from 100 to 50 yards and I was firing longish bursts all the while.

‘At this short range, I couldn’t miss and I continued firing as he climbed away fromus. When he got to about 500 feet above us, he stalled, turned over on his back and went down in a dive which rapidly became a spin. I last saw him 1,000 feet below, still going down. There was no indication that he was on fire or that the pilot had baled out. About 20 seconds later, there was an explosion on the ‘deck’ below us followed by a large fire which indicated that the Jerry had dug in. We then returned to base without further incident. I found on landing that in all I had tired about 300 rounds.

‘Let me say now that most of the credit for this successful encounter goes to the captain, as he relied implicitly on my instructions without ever seeing the tighter and he did the right thing at the right time’.

Modest words, but a typical story of the sort of encounter the bomber crews faced nightly-no heroics, just cool professionalism. But what it does prove, if proof were ever necessary, is that power operated turrets in the hands of skilled gunners and in a strong, manageable aircraft like the Wellington, were very formidable defensive weapons. This one at any rate deserved its success.

James Ward

Not all Wellington crews had it their own way, however. Although numerous decorations for gallantry and skill were won by Wellington crews, there is no doubt that many similar exploits unfortunately went unrecorded. One which was, however, properly documented is recalled by the photographs on this page. Sergeant James Allen Ward won the only Victoria Cross awarded to a Wellington crew member. How he won it can only be a source of astonishment when the circumstances are considered. Ward, a New Zealander born in 1919, was a student teacher when, in July 1940, he enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force. After training, he converted to Wellingtons at 20 OTU at Lossiemouth, Scotland and in June 1941 hejoined No 75 (NZ) Squadron, one of the 3 Group Wellington squadrons based at Feltwell, Norfolk and which in 1940 had been transferred to the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF).

Sergeant Ward’s seventh operation-on the night of July 7, 1941-was as second pilot of Wellington IC L7818.

With 40 other 3 Group aircraft from East Anglian bases he took part in a raid on Munster in Westphalia, Northern Germany-just north of the great railway yards at Hamm which had been battered continually in attacks on the Rhur. Soon after setting course for return to base, the Wellington was attacked from below by a Messerschmitt 110 night fighter and was hit by cannon fire a bullet hitting the rear gunner in one foot. He delivered a burst of fire which sent the fighter on its way, smoking and it was not seen again. The Messerschmitt had, however, done its work and the crippled Wellington, bomb doors sagging open, and fuel leaking from a ruptured pipe in the starboard wing centre section, suddenly caught fire. Quickly throttling back to as slow a speed as he dared, the Canadian pilot, Sqn Ldr R. P. Widdowson, ordered his crew to prepare to abandon the aircraft, but first to try to put the fire out, as it threatened to engulf the whole fabric-covered wing. Fire extinguisher and coffee flask were used to no avail. Sgt Ward had a look at the fire from the astro-dome amidships and then decided to try to climb out onto the wing and put out the fire with a canvas engine cover which was in use as a cushion. At first, he proposed to abandon his parachute to reduce wind resistance, but was persuaded otherwise. Despite protests by Sgt Lawton, a fellow New Zealander and navigator, Ward lowered the astrodome into the fuselage and, with a line taken from a dinghy tied to his waist, gingerly raised himself into the 90mph gale whipping past him along the top of the fuselage.

With the greatest of difficulty, Ward managed to kick holes into the smooth and taut fabric covering of the fuselage and was able to give himself enough hand and footholds to cling precariously to the outside of the Wellington. Fortunately, the wing was only about three feet below him-but it was burning in the same forced draught that was dragging at him. He managed to hang on, face down on the wing surface, gripping the structure with one hand and holding the engine cover in the other-somehow managing to persuade the flapping mass of canvas over the flames and into the hole in the fabric.

Momentarily, the flames disappeared and for several seconds-Ward held his arms in position. Then, as soon as he moved his hand, his arm by now being drained of strength, the cover was whipped away by the Slipstream and the flames reappeared-but less intensely.

Unable to do more and near exhaustion, Sgt Ward crawled back the way he had come and, with help from the navigator, managed to regain the astro-hatch and comparative safety. As he recovered inside the Wellington, he saw the fire blaze up again briefly and then burn itself out. The captain set course for home and eventually a landing was made at Newmarket without brakes or flaps, the battered Wellington trundling to a stop against the boundary fence. It never flew again, the damage had been too great. But, due to the almost superhuman endurance of the young New Zealand co-pilot, it brought its crew home. Ward was awarded the VC and his captain the DFC. The rear gunner, who had scored a victory over the offending Messerschmitt despite his wound, was awarded the DFM.

Sadly, two months after this flight, Sergeant Ward’s aircraft, of which he had been made captain, was hit by flak while on a bombing raid over Hamburg. Wellington IC X3205 fell in flames and only two of the crew escaped. James Ward was not one of them and he was later buried in Ohlsdorf Cemetery, Hamburg. His memory has been perpetuated, however, in one of the Galleries (No 6) at the Royal Air Force Museum at Hendon which is dedicated to winners of the Victoria Cross and George Cross.

ditchings

Crossing the water in wartime could be a dangerous business and an elaborate air/ sea rescue service was organised because battle damage and shortage of fuel provided the hungry seas round Britain’s coasts with plenty of aircraft and their crews. The Wellington was unusual in being provided with floatation gear as well as the usual dinghy. Flotation equipment was not itself new. Fleet Air Arm aircraft had been equipped with it in various forms for years, operating as they did from aircraft carriers.

The Wellington boasted 14 inflatable flotation bags stowed at the top of the bomb cells. Inflation was from three CO2 cylinders which were stowed in the inner wings. These were operated by levers mounted on the rear of the centre-section spar. An immersion switch, mounted immediately aft of the front turret, automatically inflated the bags on contact with salt water. The drill before ditching was to ensure that bombs, depth charges. mines, etc, were dumped and then to close bomb doors and inflate the bags at least five minutes before ditching to ensure full inflation (and not above 3,000 feet). This gave the doors the appropriate support and without this, they would collapse and the chances of the bags inflating was remote. Torpedo-dropping Wellingtons could not carry flotation gear.

There were windows at the rear end of the bomb bay through which the crew could check that the bags were inflated. All of this had to be done and checked very quickly, more often than not in complete darkness by means of a torch, usually at low level and in bad visibility, perhaps with one engine dead or even on fire, and all too often with both engines dead for lack of fuel. A ditching in such circumstances was hazardous in the extreme and crew training and discipline were of the utmost importance.

An analysis made in 1942 of a number of Wellington ditchings showed that anything from 30 seconds up to ten minutes-but more often 1-3 minutes-might be expected before the aircraft went under. If the floatation gear was operated this allowed the maximum time but, in any case, this was all too brief especially if there were injuries among the crew and obstacles in the way of the escape exits. In 24 ditchings which were analysed, there were 124 crew members and, of these, 6 were killed, 17 missing, 6 injured, 12 slightly injured and 101 unhurt. In several cases, the crews were caught unawares by the impact while moving about inside their aircraft while, in others, crews simply did not bother to take up good ditching stations.

These emphasised the importance of drill and knowing what to do automatically. Crew members were expected to be seated, braced with their backs against the rear step in the cabin or, in the case of the rear gunner. remaining in his turret so as to help the pilot by counteracting increasing nose-heaviness at the stall. Pilots were supposed to keep their Sutton harness tight and the upward-operating hatches above their heads closed until the last minute, to reduce drag. The astro-hatch had to be removed inwards before ditching. All safety precautions had to be taken before touching the sea because of the risk of injuries and subsequent incapacities caused by sudden deceleration and damage.

Since landplanes were not designed for alighting in the sea. warned an official pamphlet, it was important to make the approach as near as possible to horizontal and at the lowest safe speed. The average approach speed estimated from 16 ditchings was 74mph IAS. Flaps should be lowered 30 degrees (not more to prevent digging in). At night, the landing lamp could be a help. In every case investigated, the dinghy inflated properly, although it could become inverted and entangled in cordage. The dinghy (‘I’ type) was stowed in the starboard engine nacelle, in the hump behind the fireproof bulkhead, and inflated automatically when the immersion switch was flooded. If this failed, there were manual releases in the fuselage and under a fabric patch on the starboard wing centre section. The dinghy carried emergency survival packs although some aircraft carried these separately inside the fuselage.

The official investigation came to the conclusion that casualties from ditching Wellingtons were surprisingly low but would be lower if crews learned their drill. Training in ‘ditching’ was steadily improved and the Wellington experience served Bomber Command crews well throughout the war.