One hour that changed the war

One hour that changed the war

In the late evening of August 17, 1943, a fleet of 600 R.A.F. heavy night bombers roared out across the North Sea. The next day, the British Air Ministry's Communiqué recorded that the research and development station at Peenemünde, Germany, had been attacked.

Behind the deliberately vague language of that Communiqué lies one of the most dramatic stories of the war. Unknown to all except a handful of men, R.A.F. Bomber Command had won an aerial battle which was a turning point of the war. It remained a secret, however, for almost a year, until the first robot bombs began to crash on London. By the spring of 1943, the Allied air offensive had opened gaping wounds across the face of Germany and, to beat back our bombers, the Nazis decided to concentrate on the production of fighter planes.

Soon, with its bomber force reduced to a few hundred obsolescent machines, the Luftwaffe was unable to penetrate Britain's defences except for pinprick hit-and-run attacks. But there remained flying bombs and long-range rockets with which to satisfy the German people's demands for bombing reprisals. If these weapons could be mass-produced in time, they would enable the Germans to take the offensive in the air without using their precious bombers or airmen.

The decision was taken. Orders went out from Hitler to complete quickly the experimental development of the flying bombs and rockets and to rush them into production. The main development centre for these weapons was the Luftwaffe research station at Peenemünde, tucked away in a forest behind the beach of the Baltic Sea, 60 miles north-east of Stettin and 700 miles from England.

Into Peenemünde went the best technical brains of the Luftwaffe and the top men in German aeronautical and engineering science. In charge was the veteran Luftwaffe scientist, 49-year-old Major-General Wolfgang von Chamier-Glisezensky. Under him was a staff of several thousand professors, engineers, and experts on jet-propulsion and rocket projectiles. These scientists were set to working around the clock, for Hitler hoped to unleash his “secret weapons" during the winter of 1943-1944.

Enthusiasts believed that the secret weapons would decide the war within 24 hours. More realistic Germans hoped that they would at least disrupt British war production and delay the invasion, or perhaps force the Allies into premature invasion of the heavily defended Calais coast from which the Germans would launch their new weapons. And even if they failed to prove decisive, the reprisal bombing would bolster German morale and be useful later in bargaining for a compromise peace.

By July 1943, British intelligence reports had definitely located Peenemünde as Germany's chief spawning ground for robot bombs and rockets, A file of reports and aerial reconnaissance pictures was placed in the hands of a special British Cabinet committee, which suggested that the R.A.F. grant Peenemünde a high priority in its bombing attentions. Air Chief Marshal Harris decided to stage a surprise raid during the next clear moonlight period.

The German had become careless about Peenemünde. R.A.F. night bombers frequently flew over it on their way to Stettin and even to Berlin, and Germans working at Peenemünde used to watch British planes pass overhead, secure in the belief that the British did not know of Peenemünde's importance. A Special reconnaissance photographs for the raid were taken with great care to avoid Warning the Germans that the R.A.F. was interested in Peenemünde. They were made during routine reconnaissance flights over Baltic ports, to which the Germans had grown accustomed. These photographs enabled planners of the raid to pick out three aiming points where the most damage would be done.

The first was the living quarters of the scientists and technicians.

The second consisted of hangars and workshops containing experimental bombs and rockets. The third was the administrative area - buildings containing blue-prints and technical data.

The night of August 17 was selected because the moon would be almost full. The bomber crews were informed only that Peenemünde was an important radar experimental station; that they would catch a lot of German scientists there, and that their job was to kill as many of them as possible. After the briefing, a special note from Bomber Command headquarters was read aloud:

"The extreme importance of this target and the necessity of achieving its destruction with one attack is to be impressed on all crews. If the attack fails to achieve its object, it will have to be repeated on ensuing nights - regardless, within practicable limits, of casualties."

Nearly 600 four-motored heavies took off and roared down on Peenemünde by an indirect route. Peenemünde's defenders, apparently believing that the bombers were headed for Stettin of Berlin, were caught napping. Pathfinders went in first, swooped low over their target and dropped coloured flares around aiming points. Bombers using revolutionary new bombsights followed. Scorning the light flak, wave after wave unloaded high explosives and incendiaries from a few thousand feet on the three clearly visible aiming points.

In less than an hour the area was an almost continuous strip of fire.

As the last wave of bombers flew homeward, the German night fighters, which had been waiting in vain round Berlin, caught up with them, and 41 British bombers were lost - a small price to pay for one of the war's greatest aerial victories.

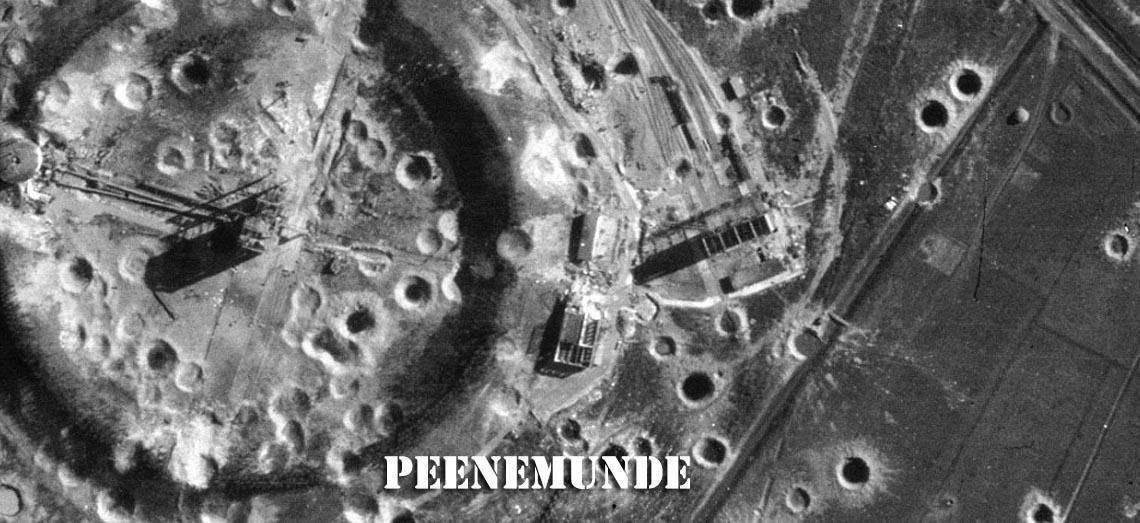

The next morning a reconnaissance Spitfire photographed the damage. Half of the 45 huts in which scientists and specialists lived, had been obliterated, and the remainder were badly damaged. In addition 40 buildings, including assembly shops and laboratories, had been completely destroyed and 50 others damaged. In a few days news of even more satisfactory results began to trickle in. Of the 7.000 scientists and 'technical men stationed in Peenemünde, some 5.000 were killed or missing. For, at the end of the raid, R.A.F.blockbusters combined with German explosives stored underground had set off such a 'tremendous blast that people living three miles away were killed.

Head scientist von Chamier-Glisezenski died during the raid.

Reports drifted out from Germany that he had been shot by agents or jealous Gestapo officials. Two days after the attack the Germans announced the death of General Jeschonnek, the Luftwaffe's chief of staff and a young Hitler favourite, who had been visiting Peenemünde, Then the Nazis admitted that General Ernst Udet, veteran aviator of the first World War and early organiser of the Luftwaffe, had met death under mysterious circumstances. It seemed likely that Udet, as head of the technical directorate of the German Air Ministry, had also been in Peenemünde.

Nazi reaction to the raid was violent. Gestapo men quizzed survivors and combed the countryside for ‘traitors who might have tipped off the RAF to Peenemünde's importance. General Walther Schreckenback, of the black-shirted secret-service, was given command of Peenemünde, with orders to resume work on the flying bombs and rockets. But all Germany's plans had to be recast. With Peenemünde half destroyed and open to further attack, new laboratories had to be built deep underground. (According to Swedish reports, these have been constructed on islands in the Baltic.)

With the best scientists and specialists wiped out, new men had to be found to carry on the developmental work.

As a result of the delay, the Nazis were unable to launch their secret weapons last winter; and they had a difficult time nursing German morale through continued Allied air raids.

The Germans were further set back by Allied air attacks during the spring of flying bomb and rocket launching ramps in the Pas de Calais, and on component parts factories. So the people were told that the secret weapons were intended as anti-invasion weapons, being saved to blast the Allies in the ports and on the beaches.

D-Day, however, caught the Germans still not ready. Not until seven days after the Allies invaded Normandy did the first flying bomb fall on London.

If Peenemünde hadn't been blasted as and when it was, the robotbomb attacks on London doubtless would have begun six months before they did, and would have been many times as heavy. London communications, the hub of Britain and nerve centre of invasion planning and preparation, would have been severely stricken. The invasion itself might have had to be postponed.

By Allan A. Michie British Digest about 1945

Footage of Peenemünde: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IN4M1p_tTKU