B-24H-1-FO - #42-7554 TAIL END CHARLIE LOST AT MIRNS - BAKHUIZEN ON 22-12-1943

The flight

Heritage Herald

E & E report (interrogation of Bevins about his escape): EE 2946

Commemoration on 11-12 November 2015:

The story by Jaap Halma

The way I came upon this story is somewhat curious. My name is Jaap Halma. I live in Joure, a small town in the Province of Friesland, in the northern part of the Netherlands. I am member of a local society of amateur historians connected with the local museum. We publish a periodical three times a year with historical facts of our Municipality.

When we reached the 25th edition, we decided to compose a book about the events during World War II in our region. I was one of the editors. During the process, I became particularly interested in the crash of the American B-24 “Las Vegas Avenger” of the 306th Bomb Group near Joure and the consequences of what we call the “Hunger winter of 1944.”

The Dutch famine of 1944, known as the Hongerwinter (“Hunger winter”) in Dutch, was a famine that took place in the German-occupied part of the Netherlands, especially in the densely populated western provinces during the winter of 1944-1945, towards the end of World War II. A German blockade cut off food and fuel shipments from farm areas to punish the Dutch for their reluctance to aid the Nazi war effort. Some 4.5 million were affected and survived because of soup kitchens. About 22,000 died because of the famine. Most vulnerable according to the death reports were elderly men.

At that time, the Allies already liberated the southern part of the Netherlands, although the central and northern parts were still occupied by the Germans. During this very severe winter, tens of thousands of children from the big cities in the center, like Amsterdam, were accommodated with families in the northern part because hardly any food was available in big cities, and thousands of people starved to death. Last year I tried to re-unite the former evacuees with those families. During one of the interviews, a man told me about the crash he had witnessed as a boy of an American bomber in the cemetery of Mirns. The story made me very curious. I had done some interesting research on the fate of the surviving crewmembers of the “Las Vegas Avenger” of the 306th Bomb Group, and even found relatives of the crew who I could tell what had happened to their loved ones. It appeared they knew little about this event and were very grateful to learn more about it. I therefore decided to do the same for “Tail End Charlie.”

This is what I found:

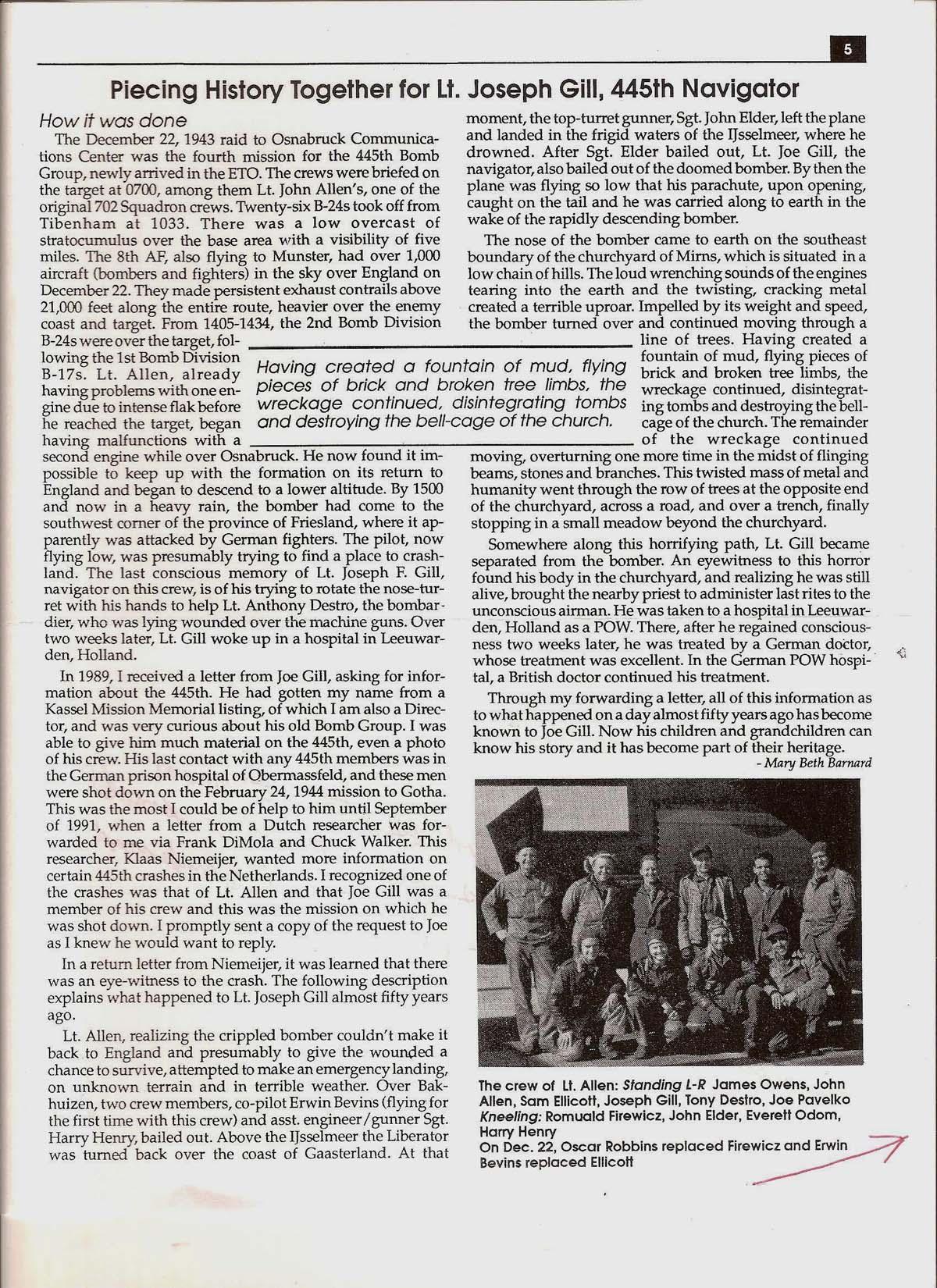

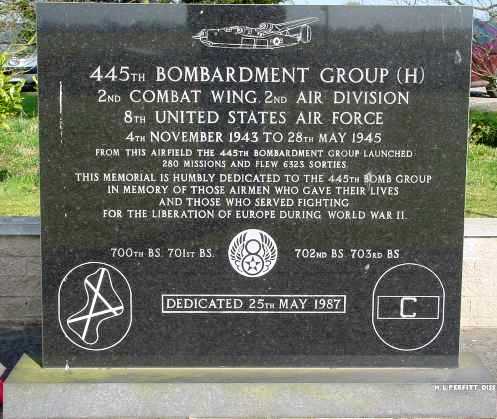

On November 4th 1943, the 445th Bombardment Group (Heavy) left from Sioux City Army Airbase, Iowa, crossed the Atlantic Ocean and stationed on the airfield of Tibenham in the English county of Norfolk, situated on the eastern coast of England. The Group consisted of the 700th, 701st, 702nd and 703rd squadrons. Curious to know: On arrival at Tibenham the famous film actor James Stewart acted as commander of the 703rd squadron; he flew 10 missions with the squadron before he transferred to the 453rd Bomb Group. (Fred Vogels: see the story of James Stewart here)

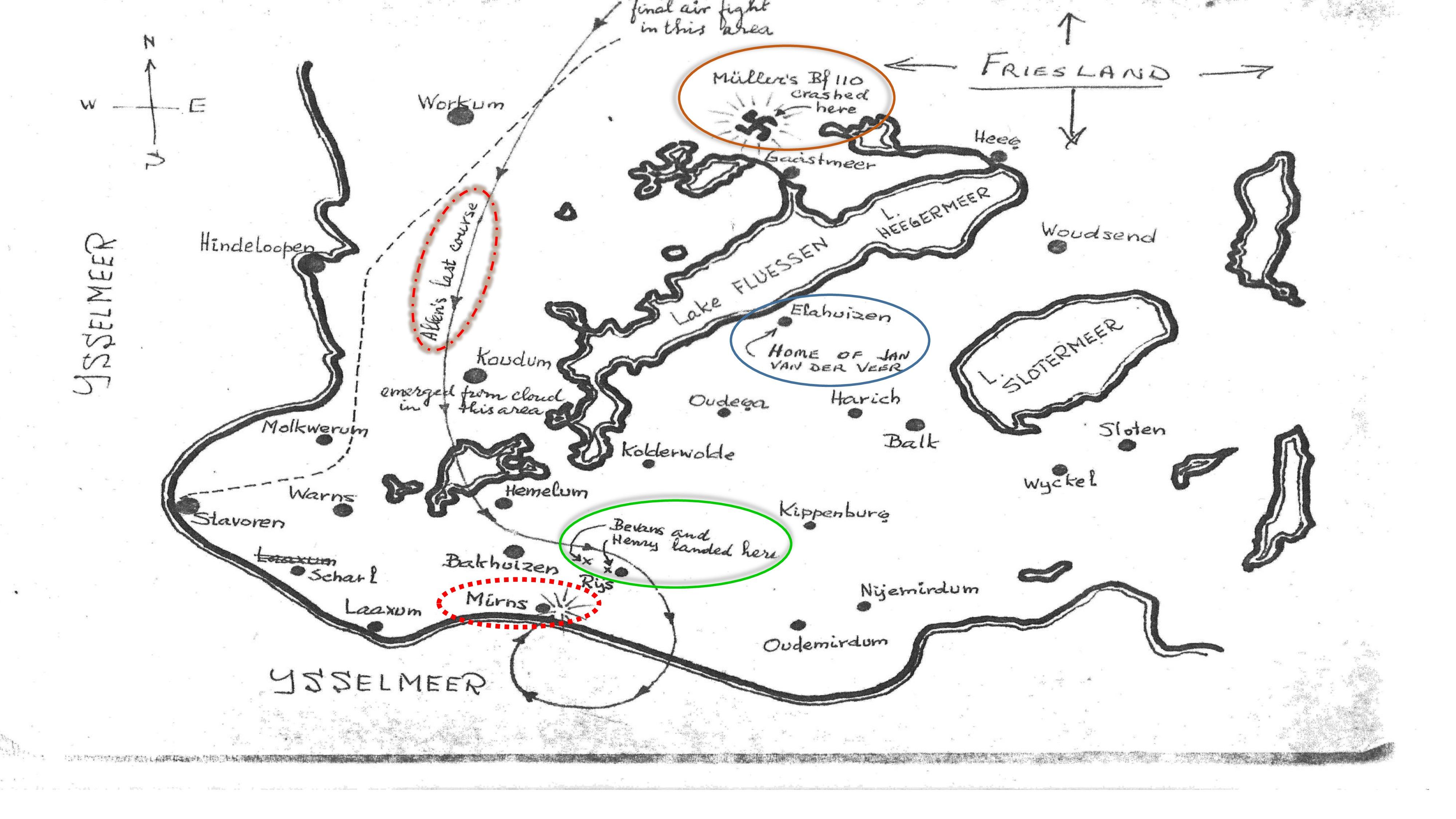

They entered combat on December 13th by attacking U-boat installations at Kiel. On December 22nd, the Group started their 4th mission and 28 Liberators left to bomb a communications centre in Osnabrück in the Northern part of Germany. 24 airplanes reached their target and dropped their bombs. It was bad weather that day, rain and low clouds limiting visibility considerably. The bombing on Osnabrück took place between 2:00 pm. and by around 3:00 pm. most planes were on their way back home.

Sadly, two airplanes would not return and both crashed in the southwestern part of the Province of Friesland, in the North of the Netherlands. Of the 20-crew members, only three would survive. German Me- 110 fighters shot down the first Liberator, no identification number known, from the 701st squadron; the ship was badly damaged with bombs still on board. The pilot tried to make a forced landing with the burning plane and hit the ground just outside the outskirts of the town of Bolsward. The whole crew perished in the flames and later the remaining bombs started to explode.

The crew were buried in the Protestant section of the church cemetery with big crowds of Bolsward inhabitants attending, defying the German occupation and honouring the heroes. The town of Bolsward donated a funeral plot, caskets and flowers. The second Liberator in the area, called “Tail End Charlie” number 42-7445 of the 700th squadron, was also fighting to stay in the protecting bomber formation.

Its crew consisted of:

- Allen, John Harold, pilot, 1st Lieutenant, from Dallas.

- Bevins, Erwin J., co-pilot, 2nd Lieutenant

- Destro, Anthony Louis, bombardier, 2nd Lieutenant, from Miami.

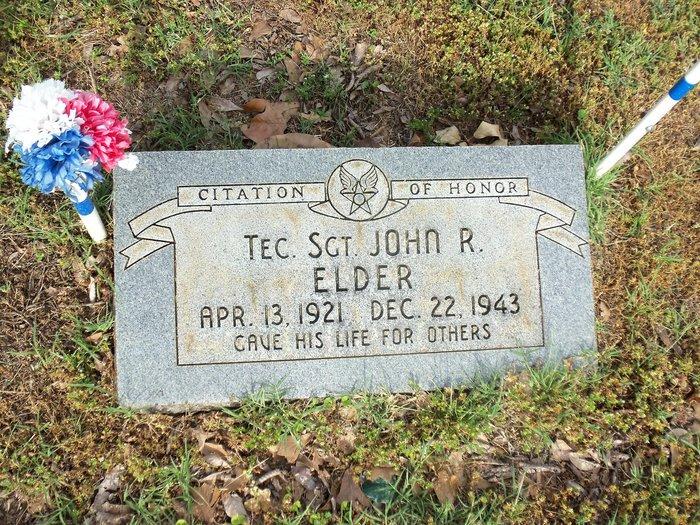

- Elder, John R., ball turret gunner, T. Sgt.

- Gill, Joseph F., navigator, 2nd Lieutenant, from New York.

- Henry, Harry L., waist gunner, Sergeant, from Philadelphia.

- Pavelko, Joseph John, belly gunner, T. Sgt., from Philadelphia.

- Odom, Everett M., tail gunner, S. Sgt.

- Owens, James C., waist gunner, T.Sgt.

- Robbins, Oscar, radio operator, T. Sgt.

The bombs had been delivered. However, on the way home a German rocket hit an engine and damaged the body construction to such an extent that doors could not be opened and communications within the plane was no longer possible. With one engine gone, the ship could not keep up with the formation and became a straggler. The German fighters found their easy prey in the area between the towns of Bolsward and Workum and went for it.

What exactly happened, we do not know. While flying above the town of Bakhuizen, Erwin Bevins, co-pilot and Harry Henry, waist gunner, aborted the plane, which continued in the direction of the IJsselmeer Lake and descended beneath the clouds. The plane made a 180 degree turn and again approached the coast, probably to avoid landing on the water and getting the head on to the easterly wind. At about this moment, Sergeant John Elder also leaves the plane. His parachute opens, but with the strong easterly winds, he drifts back to the lake and drowns in the icy water.

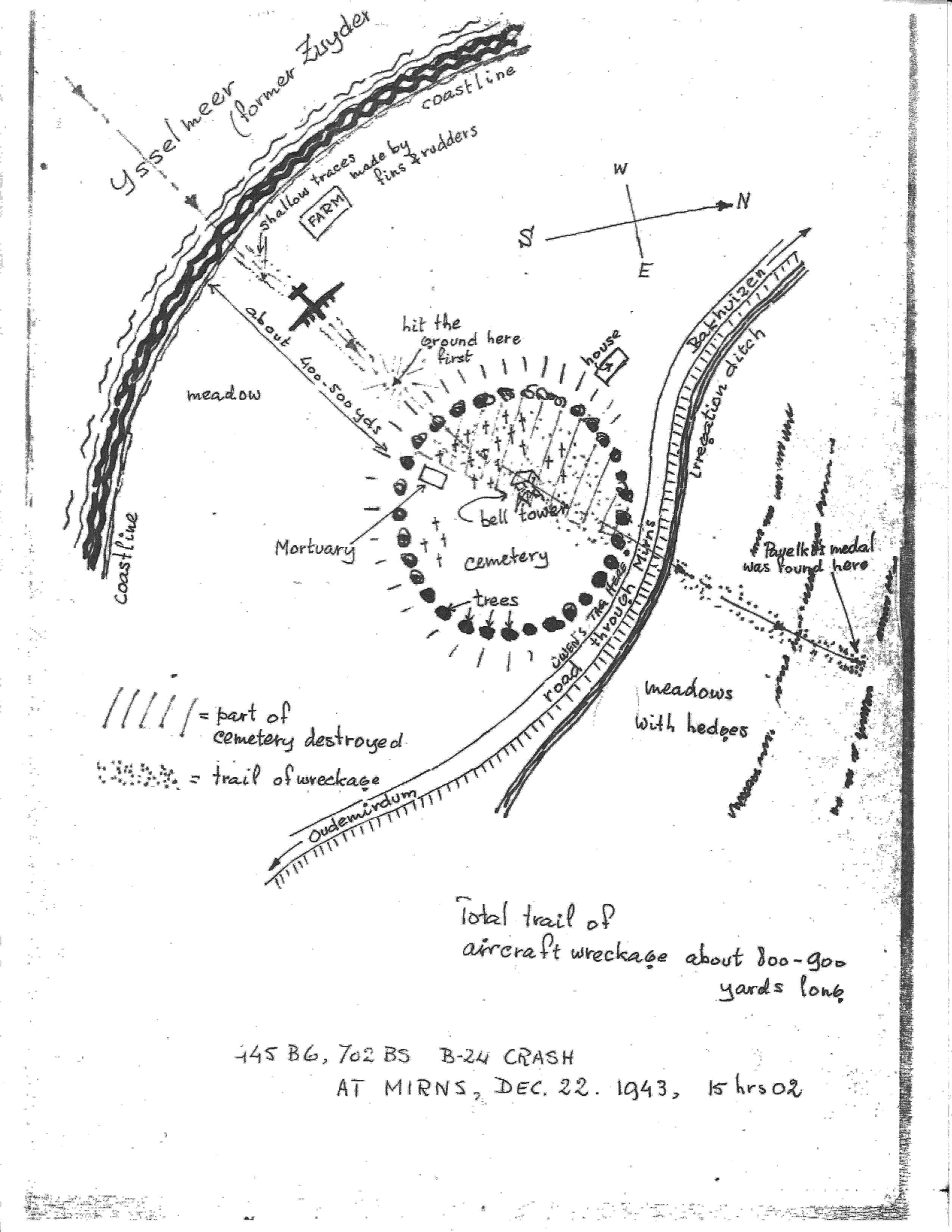

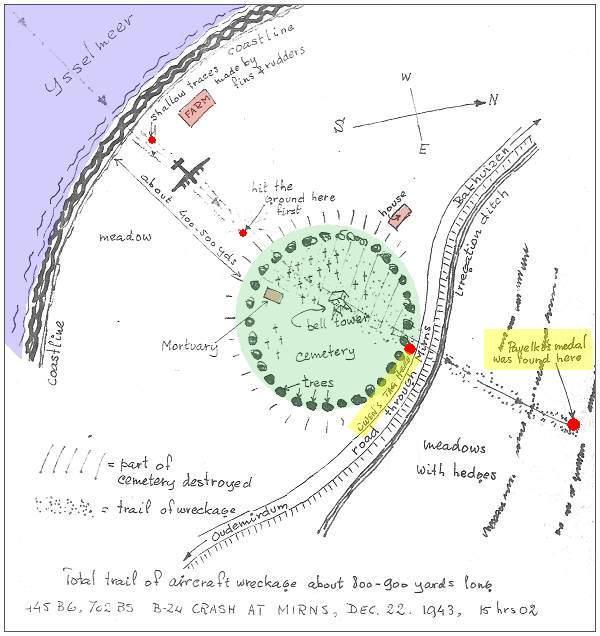

Apparently, it is pilot John Allen’s intention to land the plane on the flat fields between the shore of the lake and the hamlet of Mirns. He must have had very poor sight due to the bad weather because the flat area is quite small to make a forced landing with an aircraft of this size. Perhaps the situation of the plane also compelled him to make this impossible choice, or the fact that there were seriously wounded people on board which needed medical attention and wouldn’t survive a parachute jump. We will never know.

photo below: The field of the forced landing. At left the white bell tower of the cemetery. The plane went from the standpoint of the photographer in the direction of the bell tower. At right the Tjalma farm.

photo below : The same field but from the opposite direction. At right the Albada farm; the German barracks of the observation post were situated near the trees at left in the background. The shore of the lake is about 150 yards behind the farm.

Although the plane is too low to jump, Lieutenant Joseph Gill also takes his chance to abort. Perhaps because of the insufficient height he does not wait three seconds to open his chute, it is caught by the tail of the aircraft and Gill is pulled along by the plane until it touches the ground.The aircraft, now flying very low, passes between the German barracks and the Albada farm.

The cemetery is on a low hill, sloping down to the lake. The wildly burning plane barely avoids landing in the water and hits the slope with its nose, turning over completely and crashing through the trees of the cemetery. Next, it hits the bell tower and various gravestones, shoots through the trees on the other side of the cemetery, crosses a road, and finally comes to rest in a small wood on the other side of the road. All six remaining crewmembers perish due to the crash. The aircraft was destroyed with no more than small shreds remaining. Landing wheels were found in a field about 400 yards from the site of the crash.

The crash caused confusion in the small hamlet of Mirns. German soldiers from the observation barracks near the shore were there within a short time, along with Luftwaffe personnel from a nearby camp. They closed down the cemetery, kept people away, and left the bodies of the crew where they came down. This was a standing order from Heinrich Himmler, the head of the German police, with the intention of showing off what damage the German army could inflict on the Allies.

However, a miracle happened. Lieutenant Gill broke his jaw, and was unconsciousness but still alive! The Germans left him there without medical treatment. The inhabitants of Mirns were not allowed to enter the cemetery, except Father Schellaerts of the Roman Catholic parish of Bakhuizen and John Keulen. The latter was well acquainted with the Germans, but that was just a sham. He was active in the Dutch Underground as well as Father Schellaerts. Joseph Gill would survive but, unfortunately, they couldn’t do anything for the others.

On December 24th, the bodies of John Allen, Anthony Destro, Joseph Pavelko, Everett Odom, James Owens, and Oscar Robbins were buried at the Roman Catholic cemetery in Bakhuizen. The body of John Elder was found on the shore the day after the crash and he was buried there as well.

But, what happened to the crewmembers who aborted the plane?

Harry Henry landed in a wooded area near a hotel in the village of Rijs and was brought to the hotel. His leg was wounded, luckily not badly, but he did not know where Erwin Bevins had come down. His leg was inspected by a doctor and found in order. When civilian clothes were brought, he changed into them, and was told to stay in the hotel and later hide in the woods until it was dark.

But, there luck left him. The Germans came to know where he was and he was arrested. Henry had the good luck to be allowed to put on his uniform again, thereby regarded as a regular prisoner of war and not as an active member of the Underground. He was first transported to a German transit camp for prisoners of war where he was interrogated. Henry was later transferred to other camps near Frankfurt and Wetzlar, but survived and safely returned to the United States after the war.

In the meantime, another Dutchman had found Bevins and hid him in the woods. During the night, he was brought to a safe place because the Germans knew that two men had parachuted from the plane. Although they had arrested one, they were still looking for the other. The following day Bevins was transported in a fake ambulance operated by members of the underground from the town of Leeuwarden and went into hiding in that town. He stayed there for some time, but he’s also been traced in Laren, a small village in Eastern Holland.

A picture exists of him with the Dutch family with whom he stayed. It is unknown as to why he went there, perhaps to be closer to the Allied armies. Bevins stayed in hiding for the remainder of the war, and was never caught by the Germans. Probably he was liberated there by the Canadian Army in April 1945. Joseph Gill also became a prisoner, but was not allowed to get medical treatment at first. A fellow prisoner, a Greek dentist, later treated his jaw in the prisoner camp and he safely returned home after the war. I have also interviewed two sons of the Bruinsma family, at that time living about 100 yards from the cemetery in Mirns.

The sons Hendrik and Berend, then aged about 8-10, were at the shore of the IJsselmeer lake that afternoon to gather driftwood for the stove in the house. They were returning home via the cemetery when their mother heard the Liberator coming in very low. Because of the low clouds, they couldn’t see the aircraft. Their mother called them to come into the house immediately. Then they saw the plane coming down in flames on the cemetery at 3:02 pm., barely 100 yards from their house.

Photo left: The two Sons of the Bruinsma Family, Berend and Hendrik then aged 8-10. (Bell has been marked in Dutch to indicate ‘belltower Mirns, Friesland.’)

At that same moment three men, Gerrit Tjalma, Frans van der Werf and his son, Fimme, were gathering wood on the eastern side of the road between the cemetery and the Tjalma farm with two horses and a cart. They were all injured by burning kerosene. One of the horses was injured so badly by the wreckage that it had to be killed. Many windows were broken in the Bruinsma home and all windows in the Tjalma farm. Another house nearby was also damaged.

In the same wood where most of the wreckage came to rest, Hendrik Bruinsma later found the identification disk of John Allen of which his mother wrote down the data on a piece of paper still in possession of the family: “John H. Allen 0465407 T-430. Jetta Allen 5434 Goodwin Ave. Dallas, Texas G.” She later handed over the tag, to who is unknown. The oldest son, Ids, who was 14 years old, was visiting his father at that moment.

His father worked as a farmhand on the Draaier farm along the coast about one mile S.W. from their home. They distinctly heard the air battle and saw a big ball of flames coming down through the clouds. They were afraid that their house had been hit and went home on a bicycle as fast as they could. They were very happy there were no casualties in their family and their house hadn’t suffered heavy damage.

The Germans, from the observation post, were there very fast. An Austrian sergeant named Hans was in control until other Germans from the nearby camp in Sondel arrived and took over. Father Bruinsma tried to enter the cemetery but was repelled by the Germans. According to Ids, the day after the crash a girl called Siemke Keuning, observed from her bedroom window in the Albada farm something strange at the shore of the lake. She warned her father who went to have a look and found the body of John Elder. After the war, the bodies of John Allen, Anthony Destro, John Elder, Joseph Pavelko, Everett Odom, James Owens and Oscar Robbins were transferred to the American Military Cemetery of Margraten in the south of the Netherlands.

Still later most of them were reburied in the United States. John Allen rests in the American Military Cemetery of Neuville-en-Condroz in Belgium; Joseph Pavelko still rests at Margraten.

On August 30, 1950, Anthony Destro’s remains were exhumed and his body was re-interred in a group burial plot at the Memphis National Cemetery. He was a 1st generation American. Both of his parents came from Sicily. He was the first of his family to be born in this country. Italian-Americans were one of the largest ethnic groups to serve in the USA military during WWII. Many of Anthony’s cousins were also 1st generation who served in the military during the war. It was a great pleasure for me to write this article in honour of the people who gave their lives for our freedom.

I hope it will fill some gaps in the remembrance of relatives of these heroes. If you are interested in this story, please feel free to contract me. [email protected].

Jaap Halma

Fred Vogels: Thanks to Jaap Halma and Anthony Destro II for this story

The location and more information about this flight: CLICK HERE

Before or after Liberation?

Erwin J.Bevins on a Dutch lady’s bicycle, somewhere in the Netherlands in 1944 or 1945. Is this the smile of a defiant evadee, disguised to fool the German occupiers, and chancing death to himself and those aiding him? Or is it the smile of a liberated American who decided to ‘go native’ for a period following the war? Photographer unknown; from the collection of Jan Braakman, author of “The War in the Corner.”

(Jaap Halma's notes on this picture: Jan Lefeber sent a nice picture of 2nd Lt. Erwin J. Bevins who was co-pilot on a B-24 that was hit above the Netherlands on December 22nd 1943. The airplane crashed near Bakhuizen in the province of Friesland, in the northern part of the Netherlands. Bikes are still the main means of transport in the low

country, though during the war for many people it was the only way to get to another place. Many Dutch used the bike to transport food from the east of the country to the west during the last winter of the war, when starvation was high because of the scarcity of food. Bevins stranded in 1943. A Friesian underground worker, named Rense Talsma, picked him up. One of the many addresses Bevins frequented as an onderduiker, was the farm of Albert and Hanna Koeslag in the village of Laren. He traveled to Laren by train, according to his own account. He got food and shelter in the months of July and August. At the Koeslag farm Bevins was with 7 other evaders, Bevins told the US Military and Intelligence Service (MIS) after the war. He also remembered that Koeslag (which he erroneously spelled as Kooslag) had eleven or twelve children. From Laren he moved to the village of Nijverdal, where he stayed until the Canadian liberators came in April 1945. According to the notes he made for the MIS, he was treated for appendicitis by local practitioners. Then he moved with Lt. Ted Weaver and 30 Dutch civilians to a castle, where the 2nd Canadian Division took him and his companions. On April 9th he finally was ‘released’ to return to his own regiment. At that time he may have been a record time onderduiker. For almost one and a half year, he had been hiding with the Dutch underground.)

Extreme courage documented

Photo below: Family of Albert Jan and Hanna Koeslag (2nd row, 2nd and 3rd from the right), photographed in 1944. Farmers near the town of Laren in eastern Holland, they offered Bevins (at right, back row) a hiding place after having stayed in Leeuwarden.

Albert Jan was arrested by the Germans in November 1944 but survived the war. —photo via Gerald Martin, from the collection of Jan Braakman; photographer unknown.

Belfry of Mirns

Photo below: The belfry reminds the people of Mirns to the American bomber which on December 22, 1943 made an emergency landing here and destroyed the belfry in the cemetery, and the seven crew members who perished here .

Grave of John R.Elder

Photo below: burial John R.Elder: Memorial Park Cemetery Heavener Le Flore County Oklahoma, USA